The Wari civilization flourished in the coastal and highland areas of ancient Peru between c. 450 and c. 1000 CE. Based at their capital Huari, the Wari successfully exploited the diverse landscapes they controlled to construct an empire administered by provincial capitals connected by a large road network. Their methods of maintaining an empire and artistic style would have a significant influence on the later Inca civilization.

The Wari were contemporary with those other great Middle Horizon (c. 600 - 1000 CE) cultures centred at Tiwanaku and Pukara. The more militaristic Wari were also gifted agriculturalists and they constructed canals to irrigate terraced fields. The economic stability and prosperity this brought allowed the Wari to implement a combined strategy of military might, economic benefits, and distinct artistic imagery to forge an empire across ancient Peru. Their superior management of the land also helped them resist the 30-year drought period which during the end of the 6th century CE contributed to the decline of the neighbouring Nazca and Moche civilizations.

The Wari were undoubtedly influenced by contemporary cultures, for example, appropriating the Chavin Staff deity — a god closely associated with the sun, rain, and maize, all so vital to cultures dependent on agriculture and the whims of an unreliable climate. They transformed it into a ritual icon present on textiles and pottery, spreading their own branded iconography and leaving a lasting legacy in Andean art.

Huari

The capital at Huari (25 km north of modern Ayacucho) is located at an altitude of 2,800 m and is spread over 15 square kilometres. It was first settled around 250 CE and eventually had a population possibly as high as 70,000 at its peak. Huari shows typical features of Andean architecture: densely packed wall-enclosed rectangular structures which can be further divided into a maze of compartments. The city's walls are massive (up to 10 metres high and 4 metres thick) and built using largely unworked stones set with a mud mortar. Buildings had two or three stories, courtyards were lined with stone benches set in the walls, and drains were stone-lined. The floors and walls of buildings were generally covered with plaster and painted white.

There is little distinction in Wari architecture between public and private buildings and little evidence of town planning. A royal palace has, however, been identified in the northwest section of the city, its oldest area of habitation and called Vegachayoq Moqo. A now ruined temple was located in the Moraduchayuq compound in the southeast of the city. It was built in the 6th century CE and had subterranean parts with the whole structure once painted red. Like other buildings at the site it was deliberately destroyed and ritually buried. The city seems to have been abandoned c. 800 CE for reasons unknown.

Tombs have been excavated at Huari which contained fine examples of Wari textiles. Ceramics are also amongst finds at the site. A royal tomb was discovered in the Monjachayoq zone which consists of 25 chambers on two different levels, all lined with finely cut stone slabs. In addition, a shaft descends to a third level chamber which has the shape of a llama. Finally, a circle chamber was cut out at a fourth level down. The llama-shaped tomb, looted in antiquity, was the royal resting place and dates to 750-800 CE.

Huari was once surrounded by irrigated fields and fresh water ran through the city via underground conduits. Further indicators of prosperity are the presence of areas dedicated to the production of specific goods such as ceramics and jewellery. Precious materials for these workshops and imported goods indicate trade with far-flung places: shells from the coast and Spondylus from Ecuador, for example. The presence of buildings used for storage at Huari and other Wari cities also indicates a centrally controlled trade network spread across ancient Peru.

Pikillacta

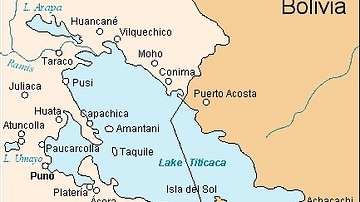

Another important Wari centre was at Pikillacta, southeast of Huari which was founded c. 650 CE. Located at an altitude of 3250 m, the heart of this administrative and military settlement site was built in a rectangular form measuring 745 x 630 metres and is laid out in a precise geometrical pattern of squares. The interiors of individual compounds are, however, idiosyncratic in layout.

As at other Wari sites, access was strictly controlled via a single, winding entrance. Notable finds at Pikillacta include 40 miniature greenstone figures depicting elite citizens and small figurines (no larger than 5 cm) of transformational shamans, warriors, bound captives, and pumas in copper, gold, and semi-precious stone. The site was abandoned c. 850 - 900 CE and there is evidence of destruction by fire of some buildings and deliberately sealed doorways.

Other important Wari cities were Viracochapampa, Jincamocco, Conchopata, Marca Huamachuco, and Azangaro. There were also purely military sites such as the fort at Cero Baul, which bordered on Tiwanaku territory to the south. These sites were connected to water sources and each other by a system of roads.

Wari Art

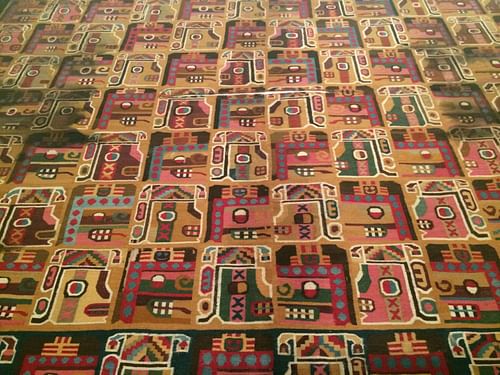

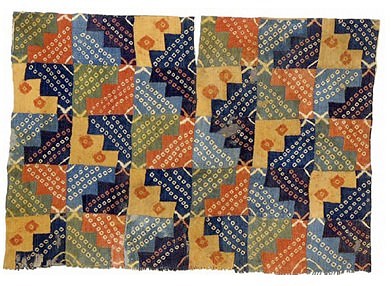

Wari art is best evidenced in textile finds which often depict the Staff Deity, plants, the San Pedro cactus flower, pumas, condors, and especially llamas, illustrating the importance of these herd animals to the Wari. Textiles were buried with the dead and those tombs in the dry desert have been well-preserved. Textiles were multi-coloured, although blue was particularly favoured, and designs were composed of predominantly rectilinear geometric forms, especially the stepped diamond motif. At the same time, despite seemingly regular geometric patterns, weavers often introduced a single random motif or colour change (typically using green or indigo) into their pieces. These could be signatures or an illustration that rules could always have exceptions.

Wari designs eventually became so abstract that figures were essentially unrecognisable, perhaps in a deliberate attempt by the elite to monopolize their interpretation. Abstract figures distorted almost beyond recognition may also be an attempt to represent the shamanic transformation and drug-induced trance consciousness which were part of Wari religious ceremonies.

Popular Wari pottery forms were the double-spouted vessels seen elsewhere in Andean cultures, large urns, beakers, bowls, and moulded effigy figures. Decorative designs were heavily influenced by those used in Wari textile production. The Staff Deity was an especially popular subject for beakers (kero) as were warriors with dart throwers, shields, and military tunics.

Precious metals were also a popular medium for elite goods. Notable finds from a royal tomb at Espiritu Pampa include a silver face mask and breast-plate, gold bracelets, and other jewellery in semi-precious stones such as greenstone and lapis lazuli. Human figures in typical Wari costume - sleeveless tunic and four-cornered hat - were also made in hammered precious metals.

The Wari Legacy

Although the exact causes of Wari decline are not known, theories range from over-extension of the empire to another period of extended drought in the 9th century CE. Whatever the reasons, the region returned to a situation of fragmented polities for several centuries.

The most lasting legacy of the Wari is their artistic style which not only influenced the contemporary Moche but also the later Lambayeque civilization, and later still, the Incas. A large number of the roads built by the Wari were also used by the Incas within their own extensive road system, as were a great number of Wari terraces for agriculture. The capital at Huari was looted in antiquity and again in the 16th century CE by the Spanish.

Re-discovered in the mid-20th century CE, the first excavations began in the 1940's and continue today, gradually revealing the wealth and power once enjoyed by one of the most important of all ancient Andean cultures.