The Lambayeque Civilization (aka Sicán) flourished between c. 750 and c. 1375 CE on the northern coast of Peru, straddling the Middle Horizon and Late Intermediate Period of the ancient Central Andes. Prodigious producers of art objects, masks, and goldwork, the Lambayeque made a significant contribution to the progression of Andean art and their legacy includes some of the most recognisable iconography from the ancient Americas.

Historical Overview

The traditional founder of the Lambayeque dynasty was Naymlap who, with an entourage of warriors, came from the south by sailing balsa boats or rafts and colonised the various valleys of the region, a legend appropriated by the later Chimu civilization. The founding city was Chot (today identified as Huaca Chotuna) and the dynasty traditionally ruled for 12 generations with the last ruler named as Fempellec, although in reality the period of Lambayeque culture probably began in the 8th century CE when it emerged from the shadows of the previously dominant Wari civilization. Rather than a unified empire the Lambayeque rulers oversaw a loose network of cities linked via bloodties.

One of the most important Lambayeque sites was Batán Grande ('Great Anvil') located in the La Leche Valley. Here a system of canals provided irrigation and 17 massive burial mounds were constructed, the largest of which is Huaca Corte which covers 250 square metres. These pyramid-mounds contained tombs with mummy bundles, sacrificial victims, and precious goods made from copper alloys, silver, and gold. Gold cups or beakers with relief figures of rulers have been found in their hundreds, for example. Batán Grande was abandoned c. 1100 CE probably due to an El Niño climate disaster (floods followed by sustained droughts) although the buildings show signs of deliberate fire destruction. Túcume then became the new religious capital and grew to cover 370 hectares making it the largest ceremonial centre ever constructed in the ancient Andes.

The centre of Lambayeque metal production was Cerro Huaringa where smelting furnaces and workshops have been excavated. Of special note are copper I-shaped ingots (naipes) which were used as a form of currency when the Lambayeque culture was at its peak between 900 and 1100 CE, a rare example in the ancient Americas.

The Lambayeque rulers seem not to have made any attempts at regional conquest but eventually they found themselves defeated and assimilated into the Chimú empire around 1375 CE and artists were forcibly relocated to Chan Chan, the Chimú capital. In this way, a continuity in Andean art passed through successive cultures and iconography such as rulers with crescent-shaped headdresses, pottery forms, and techniques in metalwork were perpetuated.

Lambayeque Art

The sheer wealth of Lambayeque society shouts out from their art and architecture. Palaces were built as massive enclosures of vast areas of land and gold is the prevalent material for all manner of goods from body ornaments to masks. Certainly not shy to display their wealth, the elite wore tunics embroidered with panels of gold; one surviving example has 2000 square gold additions, over-sized earspools in gold and turquoise, magnificent feather headdresses, and even golden gloves. The term 'conspicuous consumption' seems to have been coined with the Lambayeque elite in mind.

Typical Lambayeque pottery is their sculpted and polished blackware and the use of moulds allowed for mass production. Relief decoration can be elaborate and human faces were added near the spout, as were animal figures. The Moche-inspired double-spouted vessel is favoured but with an intricately carved bridge and a unique flared foot. Examples have also been discovered rendered in silver.

Metalwork was a Lambayeque speciality, particularly gold work where the alloy material was engraved, beaten against moulds, cut, soldered, or welded, and then inlaid. Some of the most famous art pieces from the Andes are Lambayeque, for example, gold ceremonial knives (tumi) with the handle representing a Sicán Lord. Inlaid with turquoise the figure of the handle, as in real-life, wears an impressive headdress, multiple earrings, small wings at the shoulders, a beak-like nose, sometimes with talons, and always with the distinctive Lambayeque tear-shaped eyes. The form may represent Naymlap as the legendary first ruler was said to have sprouted wings and flown off into the sunset. Tumi knives were used for ceremonies of human sacrifice involving decapitation and the functional versions had sharpened bronze blades.

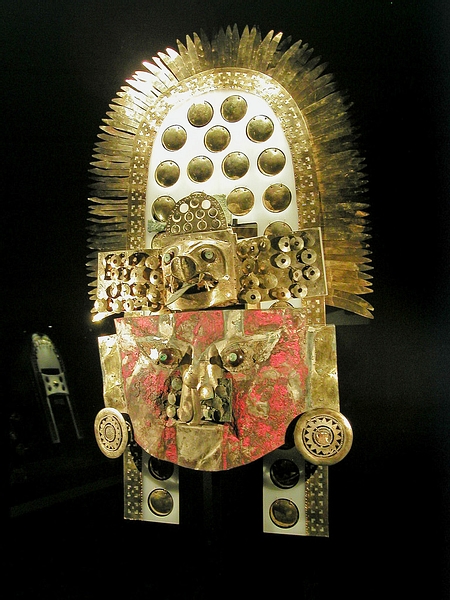

One of the most famous Lambayeque art objects is the magnificent gold mask and headdress assemblage from Tomb 1 of the Huaca Loro Burial mound at Batán Grande. The red-painted mask has earspools and a gold three-dimensional bat's head at the forehead while the tall headdress has gold feathers and 15 suspended gold disks. The mask belonged to a seated male of between 40 and 50 years of age who was buried in a 9-square-metre tomb beneath an 11-metre shaft. The ruler was accompanied into the next life with a vast array of riches, costumes, ceramics, and functional objects.

Special mention should also be made of Lambayeque litters which have been found in tombs. Made of wood and decorated with gold additions, they often contain figurines of rulers and were originally festooned with feathers. Textiles from the Lambayeque are a little eccentric compared to the neatness of other Andean weavers with borders roughly cut and back threads left loose, perhaps indicating a pressure to produce quantity rather than quality. Popular designs include animals, fish, and the standing ruler figure familiar from other art forms. Finally, shells, notably spondylus from Ecuador, were a popular form of jewellery and inlay material, a tradition which the Chimú continued following their conquest of the Lambayeque Valley.