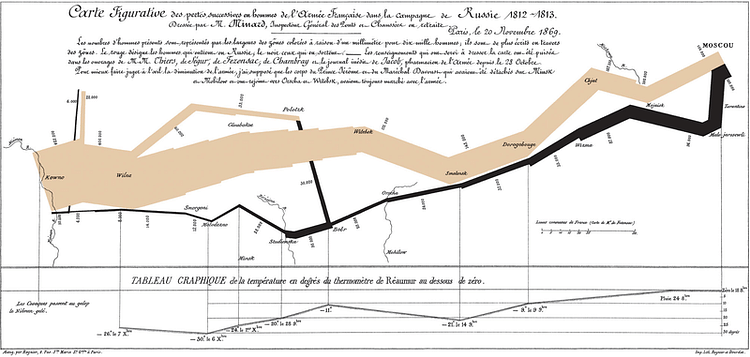

Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, also known as the Second Polish War or, in Russia, as the Patriotic War of 1812, was a campaign undertaken by French Emperor Napoleon I (r. 1804-1814; 1815) and his 615,000-man Grande Armée against the Russian Empire. It was a catastrophic defeat for Napoleon and one of history's deadliest military operations, causing approximately 1,000,000 total deaths.

Causes

In the aftermath of the Russian defeat at the Battle of Friedland (14 June 1807), the victorious French Emperor Napoleon I met with Tsar Alexander I of Russia (r. 1801-1825) on a raft in the middle of the Niemen River to negotiate peace. The subsequent Treaties of Tilsit resulted in a Franco-Russian alliance, whereby Russia was compelled to join the Continental System, a large-scale embargo against Napoleon's archrival, the United Kingdom. Russia also had to recognize the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, a French client state formed from Polish territories recently liberated from Prussia. In return, Napoleon promised to support Russia in its ongoing war against the Ottoman Empire and gave his blessing for a Russian invasion of Finland, then ruled by Sweden. The two emperors parted ways on good terms, having effectively split Europe between them.

The alliance, which clearly favored France, was unpopular amongst the proud Russian aristocrats, who were unaccustomed to losing wars and felt robbed of the chance to avenge the humiliating defeats of the last few years. Furthermore, Napoleon thwarted Tsar Alexander's ambitions to annex Constantinople and parts of the Balkans, unwilling to let Russia have access to the Mediterranean. Another point of contention was the Duchy of Warsaw and the possibility of a revived Polish kingdom on Russia's doorstep. Alexander considered this to be a threat to Russia's national security and asked Napoleon to sign a written guarantee promising that he would not resurrect Poland. Napoleon, however, saw Poland as an ideal barrier against Russian aggression and refused to do so.

Tensions between the two empires worsened in 1809 when Napoleon added West Galicia to the Duchy of Warsaw in the aftermath of the War of the Fifth Coalition. The following year, Napoleon snubbed the Russians when he broke off negotiations to marry Alexander's sister and instead married an Austrian archduchess, Marie Louise. The breaking point came on 31 December 1810, when Alexander exited the Continental System. The Russian economy was largely agrarian and relied on exports; its inability to trade with Britain, formerly Russia's primary trade partner, caused a rapid depreciation of the Russian ruble and led to a financial crisis. Napoleon felt betrayed and sought to force Alexander to rejoin the blockade; by the spring of 1811, it was clear that a new Franco-Russian war was inevitable.

Preparations

It is a popular misconception that Napoleon underestimated the challenges he would face in Russia and launched his invasion underprepared. In reality, Napoleon was acutely aware of the difficulties he would face and worked diligently to prepare for them. He had experienced a taste of Eastern European combat during his own Polish campaign of 1807 and had read accounts of the Swedish invasion of Russia undertaken by Charles XII a century before. He was well informed that the terrain he would be marching through was sparsely populated, lacked proper roads, and had little in the way of supplies. "We can hope for nothing in that countryside," the emperor wrote, "and accordingly must take everything with us" (Mikaberidze, 531). The Grande Armée would not live off the land, as was its custom, but would rely on a supply train of 7,848 vehicles that would keep it well-provisioned from supply depots in the Vistula River valley. Napoleon also understood the dangers posed by the Russian winter; but, seeing as his invasion was to begin in early summer, he intended for the war to be over by then.

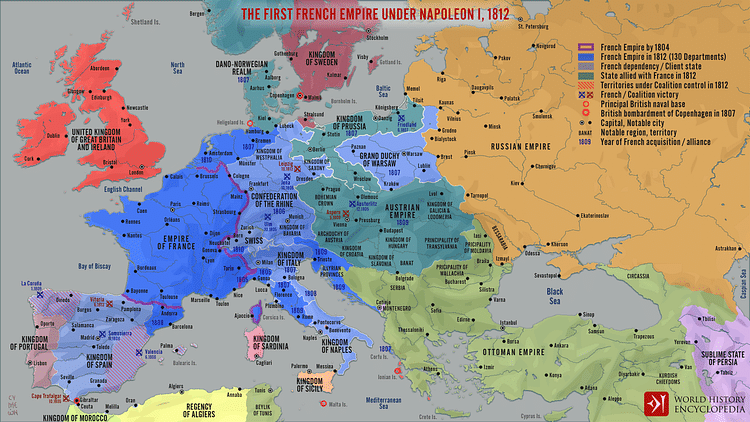

Between the autumn of 1810 and the summer of 1812, Napoleon prepared the largest invasion force Europe had yet seen. By June 1812, twelve army corps had been assembled in northern Germany and Poland, amounting to a staggering force of 615,000 men. Slightly less than half (302,000) of these troops were Frenchmen, with the rest hailing from all corners of French-occupied Europe. These included 90,000 Poles and Lithuanians, 190,000 Germans (including troops from Austria, Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Hesse, Baden, and Westphalia), and 32,000 Dutch, Swiss, Italians, Spanish, and Portuguese. Apart from the French and Poles, however, few of Napoleon's troops felt any affection for their emperor nor enthusiasm for his cause and were serving out of duress. This army also included approximately 200,000 horses and 1,372 guns.

This massive Grande Armée was divided into three lines. The first line was positioned along the Niemen River, the border with the Russian Empire, and consisted of 449,000 men. It was subdivided into three separate armies: the principal army, commanded directly by Napoleon, included three army corps led by marshals Louis-Nicolas Davout, Nicolas Oudinot, and Michel Ney, and a cavalry corps led by Joachim Murat, King of Naples. It was supported by two auxiliary armies; the first was led by Napoleon's stepson, Eugène de Beauharnais, Viceroy of Italy, and the other by Napoleon's brother, Jerôme Bonaparte, King of Westphalia. The emperor's decision to entrust these commands to inexperienced family members instead of hardened generals has long been a point of criticism. The second line of around 165,000 men would provide replacements for the first line, while the third line of 60,000 would guard the rear.

Russia, meanwhile, had 650,000 soldiers in the field in 1812, but these were scattered across its vast empire; it only had around 250,000 men and 900 guns in the western provinces available to oppose Napoleon. These were divided into three armies: the First Western Army, led by Mikhail Barclay de Tolly, was positioned near Vilna (Vilnius) with 129,000 men, the fiery Prince Peter Bagration led the 58,000-man Second Western Army about 160 kilometers (100 mi) to the south, while the 43,000-man Third Western Army was marching up from the Balkans.

Crossing the Niemen

On 23-24 June 1812, Napoleon crossed the Niemen River; it was, in many ways, the Napoleonic equivalent of Julius Caesar's crossing of the Rubicon. The first elements of the army set foot on Russian soil uncontested; the nearby Cossack cavalry fired only three shots before riding away. As Napoleon watched the seemingly endless stream of troops file across the river, his horse was startled by a rabbit, causing it to throw off the emperor. Though Napoleon was left with only a bruised hip, this was widely interpreted as a bad omen.

Napoleon's intention was not to conquer Russian land, but rather to destroy the Russian armies, thereby forcing Tsar Alexander to submit to French will and rejoin the Continental System. It was, therefore, not a war of conquest but a war of control; by punishing Russia for its insolence, Napoleon would ensure that the rest of Europe remained subservient. His plan was to engage the enemy in a sweeping maneuver through Vilna, destroying each Russian army piecemeal before they had a chance to converge. Napoleon hoped to win the war within three weeks.

Barclay de Tolly, commander-in-chief of the Russian armies, guessed at Napoleon's intentions and resolved to deny Napoleon the battle he desired by luring the French army deep into Russia. This strategic retreat would be combined with a scorched earth policy, whereby the Russians would deny the enemy anything of value; as they retreated, the Russians destroyed crops, windmills, bridges, livestock, and depots. Barclay's planned war of attrition was supported by the Baltic German officers in the Russian army, of whom Barclay was one; however, the Russian-born officers felt dishonored by the retreat and wanted to stand and fight. Friction soon arose between the two groups.

Scorched Earth

On 28 June, Napoleon entered Vilna and was greeted with great fanfare from the local populace. As the emperor held military parades to celebrate Lithuania's 'liberation', he was disappointed that the Russians had abandoned the place without a fight. Napoleon stayed in Vilna for ten days, while the auxiliary army under King Jerôme Bonaparte advanced toward the Berezina River to trap Prince Bagration's army. However, heavy rains and searing heat slowed Jerôme's advance, allowing Bagration to escape; after being scolded by his imperial brother, Jerôme resigned his command in a rage and returned to Westphalia. On 8 July, Napoleon learned that Barclay's First Western Army was at the powerful fortress of Drissa and set out to catch him, but he found the fort abandoned on 17 July. Bagration, meanwhile, had slipped once again from French clutches, avoiding battle when French Marshal Davout captured Minsk. On 23 July, Davout fought Barclay in the first real battle of the war at Saltanovka, forcing Barclay to withdraw further, to Smolensk.

By this point, the campaign was a month old, and already the Grande Armée had suffered grievous losses. The scorching summer heat combined with torrential rains meant that many men fell sick; by the third week of July, over 80,000 men were either dead or seriously ill from diseases such as typhus and dysentery. Combined with the deserters, Napoleon had already lost 100,000 men before the first major battle was even fought. The French supply train became hindered by the lack of quality roads and, along with the Russians' scorched earth tactics, this led to rampant starvation and malnutrition. This was particularly true for the horses, who had nothing to eat but unripe rye and began dying en masse, with an average of 1,000 horses dying every day of the 175-day-long campaign. As the Grande Armée continued its miserable trek into Russia, it left a trail of putrefying human and animal corpses in its wake.

On 4 August, Bagration joined Barclay at Smolensk. By this point, the Russian faction and the Baltic German faction were at each other's throats, and the Russian officers even threatened mutiny if Barclay did not stand his ground and fight. Reluctantly, Barclay began planning an offensive. Napoleon was elated, finally seeing his chance to fight a much-needed battle. He wasted no time launching his own counteroffensive, the 'Smolensk Maneuver'; this was an impressive operation in which Napoleon quickly moved over 200,000 men across the Dnieper River and began advancing on Smolensk. However, the French advance was stymied on 14 August, when the Russian rearguard made a heroic, yet suicidal, stand at the First Battle of Krasnoi. The French wasted the next day, Napoleon's 43rd birthday, conducting a series of useless army inspections, allowing Barclay time to fortify Smolensk.

The Battle of Smolensk (16-18 August) was the first large-scale battle of the war. The city became engulfed in flames as the armies engaged in bloody hand-to-hand fighting in the suburbs. Although the Russians withstood several French assaults, they were eventually forced to retreat toward Moscow. The battle, though technically a French victory, was not the decisive engagement that Napoleon needed and had been too costly, resulting in 10,000 French losses and around 12,000 Russian casualties. Napoleon seriously considered wintering in Smolensk, but he knew any pause would be construed as a defeat. He had little choice but to push on toward Moscow.

Borodino & Moscow

Barclay's decision to abandon Smolensk caused an uproar in St. Petersburg, and he was replaced by the popular 67-year-old veteran Mikail Kutuzov, who had fought Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz (1805). Kutuzov continued to retreat deeper into Russia before choosing to make a stand at Borodino, about 120 kilometers (75 mi) from Moscow. It was here, on 7 September, that Napoleon got the decisive battle he had been craving, though at a horrendous price. The Battle of Borodino lasted twelve hours and involved 300,000 men. It was the bloodiest single day of the Napoleonic Wars, resulting in 35,000 French and 45,000 Russians killed (including Prince Bagration) or wounded. At the end of the day, Kutuzov decided to withdraw and continue the war of attrition. Though this opened the road to Moscow, the Russian army remained intact, destroying Napoleon's hopes of forcing a surrender.

On 14 September, Napoleon entered Moscow to find its streets deserted; Moscow governor Fedor Rostopchin had ordered the evacuation of the city's 250,000 inhabitants and had set fire to the supply depots. Dry weather and strong winds ensured that this small fire blossomed into a conflagration that soon engulfed the entire city. Since the fire equipment had also been evacuated, Napoleon had no means to put the fire out; his troops were thus deprived of provisions and shelter and were forced to resort to pillaging. Discipline quickly broke down.

Napoleon spent 36 days in Moscow, desperately hoping to reach a peace agreement with the tsar, in St. Petersburg. Moscow was Russia's largest city and held much cultural and historic significance, leading Napoleon to believe its capture would force Tsar Alexander's hand. However, the resolve of the tsar and the Russian people was much firmer than Napoleon anticipated. On 18 October, Napoleon realized that no peace was forthcoming. The autumn weather was still good and, unwilling to be trapped in Moscow for the winter, Napoleon ordered a retreat.

Retreat

By the time Napoleon made the decision to abandon Moscow, his army had dwindled to only 100,000 men. Though they had survived the brutal summer fighting, the worst suffering was still to come. Autumnal rains turned the roads into muddy soup, gridlocking the Grande Armée and leaving it open to guerilla attacks from the pursuing Cossacks. Kutuzov's main army was not far behind and clashed with the French at the Battle of Maloyaroslavets (24 October). Though the battle was a French tactical victory, Kutuzov was able to prevent the French from reaching the abundant southern provinces, forcing Napoleon to retreat along the devastated route by which he had come.

The retreat soon turned into a disordered rout, as the surviving soldiers could think only of getting out of Russia as soon as possible. Morale plummeted further as the Grande Armée marched through the Borodino battlefield, where thousands of corpses remained unburied, half-eaten by wolves. By early November, the onset of Russian winter hit the Grande Armée like a sledgehammer as temperatures dropped to -30°C. Soldiers suffered from snow blindness, their breath turning to icicles as it left their mouths. Many lost their way and froze to death, others merely collapsed and died where they lay. Comradeship quickly broke down, as men were charged a gold louis merely to sit by a fire, and fights broke out over food and water. There were also several instances of cannibalism.

Napoleon reached Smolensk on 9 November, his fighting strength reduced to only 60,000 men. Almost all the horses were dead by this point, and most of the artillery guns had been spiked and left on the roadside; neither Napoleon's cavalry nor his artillery would recover from this. Most of the remaining provisions in Smolensk were eaten on the first day, but since it took the whole army five days to gather, those who arrived last got nothing. The winter inflicted a heavy toll on Kutuzov's army too, which had been whittled down from 105,000 men to 60,000. As the French army left Smolensk, it fought a series of engagements in the Second Battle of Krasnoi (15-18 November), which cost the French around 30,000 losses. French Marshal Ney distinguished himself by making a fighting retreat across the Dnieper after his corps was separated from the main army.

As Napoleon approached the Berezina River, Kutuzov saw a chance to trap him; Russian General Peter Wittgenstein's corps was sent northeast while Pavel Chichagov's army approached from the southwest. The Russian forces converged on the remnants of Napoleon's army at Borisov; heavy fighting lasted there from 26-29 November as Napoleon's Dutch engineers hurriedly built a pontoon bridge across the freezing Berezina. The core of Napoleon's army then conducted a chaotic and deadly crossing; thus, the Grande Armée escaped destruction at the cost of 40,000 losses, most of them stragglers or civilian camp-followers. Days later, the Grande Armée recrossed the Niemen. On 5 December, Napoleon appointed Murat to command the army as he hurried back to Paris to minimize the political fallout.

Aftermath

The French invasion of Russia remains one of the most famous military disasters in history. Of the 615,000 French and allied troops who crossed the Niemen in June 1812, fewer than 100,000 would stagger back across half a year later; of those survivors, thousands were suffering from frostbite or starvation, and many were permanently crippled. Of the half million losses, around 100,000 had deserted and 120,000 taken prisoner; the corpses of the remaining 380,000 troops were buried beneath the Russian snow. Russian losses are more difficult to assess; around 150,000 Russian soldiers likely died from all causes, with at least twice as many more wounded. An unknown number of Russian civilians died, but the combined total of military and civilian deaths likely surpassed one million. The invasion remains one of the deadliest military operations in history.

Napoleon never truly recovered from this catastrophe; while he quickly raised new infantry conscripts, he was unable to replace the cavalry and artillery losses. Meanwhile, the Russian army did not stop at the Niemen but continued its advance into Europe; it was soon joined by the armies of Britain, Prussia, and Austria, beginning the War of the Sixth Coalition (1813-1814), the conflict that would topple Napoleon's empire.