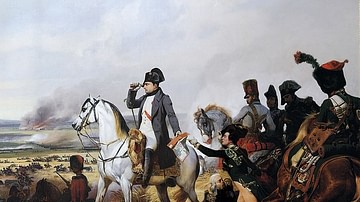

The War of the Fifth Coalition (1809) was a major conflict of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) that was fought primarily in Central Europe between the First French Empire and its client states against the Austrian Empire, supported by the United Kingdom. The six-month conflict was the final victorious war in the career of Emperor Napoleon I (r. 1804-1814; 1815).

Previously, Austria had suffered several major defeats at the hands of Napoleon in 1797, 1800, and 1805 and had been forced to give up much of its lands and influence in Central Europe. Eager to reclaim its lost territories, the Austrians reformed their army and invaded the Kingdom of Bavaria, Napoleon's strongest German ally, on 10 April 1809. Although the French were caught by surprise, the Austrian offensive got off to a slow start, allowing Napoleon time to concentrate his forces and win a string of victories in the week-long Landshut campaign. On 13 May, Napoleon seized the Austrian capital of Vienna and prepared to cross the Danube River to finish off the Habsburg army led by Archduke Charles of Austria. However, Archduke Charles attacked as the French were crossing the river; the subsequent Battle of Aspern-Essling (21-22 May) marked Napoleon's first defeat in ten years.

Napoleon was forced to retreat to Vienna, where he rallied his army, and he attempted a second crossing a month later. Having learned from his mistakes, Napoleon won the decisive Battle of Wagram (5-6 July), the largest battle in European history until that point. Days later, Archduke Charles asked for an armistice, and peace was finalized at the Treaty of Schönbrunn (14 October), which saw Austria surrender large chunks of land that amounted to 20% of its population. The peace was sealed by the marriage of Napoleon to the Austrian princess Marie Louise in 1810. The war also saw several secondary fronts in Italy, Poland, and Holland, and coincided with a major anti-Napoleonic rebellion in Tyrol, which ultimately failed.

Origins

Following its humiliating defeat at the Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805), the Austrian Empire was forced to surrender most of its territory in Italy and southern Germany, along with Tyrol, which was awarded to Napoleon's stalwart ally of Bavaria. At a stroke, the Habsburgs were deprived of regions that had once formed the heart of their empire, and many key ministers in Vienna resented Napoleon for the loss. Over the next three years, a war party developed, centered around the empress consort Maria Ludovika, and involving powerful officials like Foreign Minister Johann Philipp Stadion. This war party believed that Napoleon sought to dethrone the Habsburgs and absorb the Austrian Empire and that their only chance of survival was to strike Napoleon first. An opportunity would present itself in 1808, as hundreds of thousands of French soldiers were deployed to Iberia to fight in the Peninsular War (1807-1814). With France's military presence in Germany greatly diminished, Stadion moved to build a fifth anti-French coalition.

He first approached the United Kingdom, which agreed to pay Austria a large subsidy. Stadion next sent emissaries to Prussia and Russia, but both nations declined to join the fight against Napoleon. Prussia had recently lost half its territories after it was defeated in the War of the Fourth Coalition and was convinced that another defeat would see it wiped from the map. Russia was a French ally as stipulated by the Treaties of Tilsit and was unwilling to betray the alliance quite yet. However, ministers in each nation quietly offered words of encouragement to the Austrian emissaries, with one Prussian official even remarking, "a single victory and the universe will rise against Napoleon" (Mikaberidze, 307). Indeed, it seemed to be a widespread belief that a mass uprising was imminent in French-occupied Germany that was waiting to be ignited. Under this assumption, Emperor Francis I of Austria ordered his brother, Archduke Charles, to mobilize the army for war.

Archduke Charles had been appointed commander-in-chief of the Habsburg forces in the aftermath of Austerlitz and had spent three years reforming the Austrian army. Having fought the French since 1793, Charles was familiar with what made the French armies so effective and sought to bring those aspects to his own army. One such reform was the implementation of the corps d'armee system, which would hopefully afford the Austrian army a greater degree of flexibility; nine line and two reserve corps were created. Charles also adopted a French-style system of mass conscription through his new Landwehr militia, whereby 180,000 males between the ages of 18-45 in the empire's German-speaking provinces were eligible to be drafted to supplement the regular army of 340,000. Yet Austrian tactics remained antiquated, and the corps system lacked properly trained officers. Charles asked his brother for more time to finish his reforms, but Emperor Francis refused, believing that they would never get a better chance to destroy Napoleon.

The build-up of Austrian forces did not go unnoticed by Napoleon, who began raising a new army in early 1809. Most of these 230,000 men were raw French recruits or German troops from the French-allied Confederation of the Rhine. Dubbed the Army of Germany, this force was sent east of the Rhine River to deter Austrian aggression, and Napoleon recalled some of his best marshals from Spain to command the corps; overall command of the army was given to the emperor's chief of staff, Marshal Louis-Alexandre Berthier. Napoleon believed that the presence of this army in Germany would dissuade Austria from attacking until at least May. He was surprised, therefore, when he learned that Archduke Charles had invaded Bavaria on 10 April 1809 with 200,000 men. The War of the Fifth Coalition had begun.

War Along the Danube

Although Marshal Berthier was a brilliant chief of staff, he was less adept at commanding armies. Upon learning of the Austrian invasion, Berthier panicked, ordering his troops on useless marches and countermarches and misinterpreting the orders that Napoleon hurriedly scribbled to him. Consequently, the army was dangerously spread out, with corps scattered between Augsburg and Munich, and the III Corps of Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout isolated far ahead of the army at Ratisbon, vulnerable to encirclement. This could have been disastrous for the French, but the Austrian offensive got off to a painfully slow start and lost the advantage of surprise. By the time Charles' army crossed the Isar River on 17 April, Napoleon had arrived to take command from a relieved Berthier.

Napoleon's main priority was to concentrate his army. He ordered Davout to slip out of Ratisbon and join up with Marshal François-Joseph Lefebvre's Bavarian corps near Abensberg; Davout and Lefebvre would pin down the Austrian advance while the rest of the French army marched to Landshut to threaten the Austrian rear. On 19 April, Davout marched out of Ratisbon and successfully linked with Lefebvre, after beating back an Austrian assault at the Battle of Teugen-Hausen. The next day, Napoleon's main army defeated the Austrian V Corps at the Battle of Abensberg, resulting in 10,000 Austrian casualties. The French seized Landshut on 21 April but hardly had time to bask in their victory before learning that Davout and Lefebvre's 36,000 men were defending against 75,000 Austrians near Eckmühl. Napoleon raced north and defeated Archduke Charles at the Battle of Eckmühl (22 April). The Austrians retreated behind the medieval walls of Ratisbon, but French Marshal Jean Lannes scaled the walls and forced Charles to retreat further, beyond the Danube River. The week-long Landshut campaign was a French success, made more impressive by the fact that Napoleon's army was largely comprised of conscripts.

Instead of pursuing Charles, Napoleon opted to march toward the undefended Austrian capital and seized Vienna on 13 May. Emperor Francis had evacuated the city, and Charles had rallied his army, which was now encamped on the opposite side of the Danube, to the north and east of Vienna. Realizing that any delay would only benefit the Austrians, Napoleon went on the offensive; on 20 May, he had a bridge built at Lobau Island and began moving his army across the Danube. The first elements of his army got across without issue and occupied the towns of Aspern and Essling. However, attempts to get the rest of the army across were frustrated by rising water levels and by the Austrians, who floated barges down the river to punch holes in the bridge.

Napoleon was now caught in an awkward position, with his army straddling both banks of the river. Charles took this opportunity to attack, commencing the bloody Battle of Aspern-Essling. After two days of fighting, Napoleon found that he was unable to get the rest of his army across and was forced to order a withdrawal, marking his first major defeat in ten years. The Austrians paid a steep price for their victory, having lost around 23,000 casualties, while the French lost a similar number, including the invaluable Marshal Lannes. As Napoleon's army limped back to Vienna, Charles neglected to pursue, and a lull descended on the Danube campaign.

Italian, Polish, & Dutch Fronts

As the main campaign of the war was being waged in Germany, secondary campaigns were being fought elsewhere. When Archduke Charles launched the main invasion of Bavaria, his younger brother, Archduke John, invaded northern Italy with 50,000 regular troops and perhaps as many Landwehr. John was opposed by French and Italian troops led by Napoleon's stepson, Eugène de Beauharnais, Viceroy of Italy. On 16 April, Archduke John repulsed a Franco-Italian attack at the Battle of Sacile, forcing Beauharnais to withdraw beyond the Adige River. Beauharnais did not take long to lick his wounds and attacked John again in a series of inconclusive engagements near Caldiero (27-30 April). John received word of his brother's defeat in Bavaria and began to move in defense of Vienna; Beauharnais pursued and won a victory over the Austrians at the Piave River (8 May). The defeat forced John to withdraw into Inner Austria, where he was defeated by Beauharnais again at the Battle of Raab (14 June). This time, John's battered army withdrew to Pressburg (modern Bratislava) as Beauharnais led his 23,000 men to join his stepfather at Vienna.

Meanwhile, Poland was invaded by an Austrian army led by yet another Habsburg brother, Archduke Ferdinand. Ferdinand's task was to defeat the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, a newly created French client state, before striking across the Elbe to attack the French rear. At the Battle of Raszyn (19 April), the Austrians defeated a newly raised Polish army led by Prince Józef Poniatowski and occupied Warsaw four days later. However, Poniatowski marched along the Vistula River and invaded Austrian Galicia, forcing the surrender of several Austrian garrisons and setting up a Polish administration. Ferdinand was forced to abandon Warsaw on 1 June to meet the Polish threat, and the Poles reclaimed their capital a week later. On 10 June, a Russian army entered Galicia; though the Russians were technically allied to Napoleon, General Golitsyn had been instructed not to engage the Austrian army. In fact, the Russians seemed more hostile to their supposed Polish allies, leading Poniatowski to complain to Napoleon. Nevertheless, the Austrians had been expelled from Poland and Galicia by the end of June.

Another front was opened in Holland, when a 37,000-man British expeditionary force landed at Walcheren on 30 July. Commanded by John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, the goal of the Walcheren Expedition was to relieve some of the pressure from Austria and encourage the Habsburgs to keep fighting. However, the expedition got off to a slow start due to poor leadership and was soon faced with a 40,000-man Franco-Dutch force. The British remained in Holland for several weeks, but soon suffered from a deadly combination of malaria and typhus known as "Walcheren Fever"; while only 106 British soldiers died in combat during the expedition, approximately 4,000 were killed by the disease. On 30 September, the failed expedition was called off, and Chatham's army was evacuated.

Uprisings

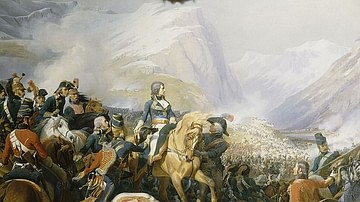

Although there was no mass German uprising, as had been expected by the Habsburg court, pockets of anti-Napoleonic resistance did break out. The most famous example was Tyrol, which had long been part of the Habsburg realm until it was ceded to Bavaria as part of the Treaty of Pressburg (1805). The Tyrolean peasants loathed their new Franco-Bavarian overlords, who closed local assemblies, imposed new taxes, and conscripted Tyroleans to fight in Napoleon's armies. When Archduke Charles invaded Bavaria in April 1809, the Tyroleans seized their chance to rebel. Led by an innkeeper named Andreas Hofer, the rebels surprised and overwhelmed the Bavarian garrisons at Sterzing and Innsbruck, taking 6,000 prisoners and large quantities of supplies. On 10 May, the Bavarians retook Innsbruck but only occupied it for ten days before Hofer renewed the struggle and won a major victory at the Second Battle of Bergisel (29 May).

By this point, Napoleon was focused on defeating Archduke Charles and could not afford to send troops to crush the Tyrolean Rebellion. Thus, the rebellion continued to spread, even spilling over into Italy, where similar revolts broke out in the former Venetian provinces and in Emilia-Romagna. With the support of the Austrian Landwehr, the Tyroleans were able to free their country from Bavarian occupation by July. However, the terms of the Armistice of Znaim stipulated that the Austrians had to evacuate Tyrol, leaving the rebels to fight alone. In August, French Marshal Lefebvre invaded with 40,000 Franco-Bavarian troops, and the rebels took to the mountains to embark on a campaign of guerilla warfare. Although the Tyroleans scored victories at Sterzing (6-9 August) and the Third Battle of Bergisel (13 August), they were eventually overwhelmed by the Franco-Bavarians and defeated. Many rebels accepted amnesties, but those who held out were ruthlessly hunted down. Hofer himself was captured and executed on 10 February 1810. The Italian revolts were similarly crushed around the same time.

Another significant revolt took place in northern Germany where Major Ferdinand von Schill, a renegade Prussian officer, attempted to instigate a large-scale uprising. At the head of his hussar regiment, Schill marched out of Berlin on 28 April and won a minor victory against a Franco-Westphalian force south of Magdeburg. However, Schill was hunted down by a French-allied Dutch and Danish force and was killed in action at Stralsund, becoming a martyr for the German liberation movement. Another anti-Napoleonic German leader was Duke Frederick William of Brunswick-Oels, who had been deposed from his duchy by Napoleon in 1807 and whose father was killed at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt. Brunswick raised a volunteer corps that wore black uniforms and sported the Totenkopf ("death's head") badge; his corps would become known as the "Black Brunswickers". Brunswick defeated several Saxon and Westphalian forces and helped the Austrians capture the Saxon capital of Dresden. The Black Brunswickers refused to recognize the Armistice of Znaim and instead continued to fight the French in Iberia, in the service of the British army.

Wagram & Peace

By July, Napoleon had concentrated nearly 160,000 soldiers at Vienna with many more on the way. He decided that the time had come to attempt another crossing of the Danube and began moving vast quantities of men onto Lobau Island. Having learned from his mistakes, Napoleon succeeded in moving most of his army across the river during the night of 4-5 July, as the Austrians took up defensive positions on the heights behind the Russbach River. On the morning of 5 July, Napoleon ordered a general assault, beginning the Battle of Wagram, the largest battle in European history until that point. The next two days of bloody fighting produced 32,000 French and 37,000 Austrian casualties but ultimately resulted in a pyrrhic victory for Napoleon. Archduke Charles withdrew from the heights and retreated to Znaim, where he was attacked by French troops under Auguste de Marmont on 10-11 July. Charles had lost the stomach for battle and agreed to the Armistice of Znaim on 12 July, ending hostilities between the French and Austrian armies.

This began months of lengthy negotiations between Napoleon and Prince Klemens von Metternich, the brilliant Austrian diplomat. Since Napoleon had lost Aspern-Essling and had failed to destroy Charles' army at Wagram, Metternich had some leverage and was able to secure lighter terms for Austria, retaining most of the Habsburgs' hereditary lands. Still, when the Treaty of Schönbrunn was signed on 14 October 1809, Austria paid a heavy price, ceding Carinthia, Carpathia, and all its Adriatic ports to France, thereby losing access to the Mediterranean Sea. Austria also had to give West Galicia to the Duchy of Warsaw and the district of Tarnopol to Russia; in all, the Habsburgs lost 3 million subjects with these cessations. Emperor Francis was also compelled to pay an 85-million-franc war indemnity, join the Continental System against Britain, and recognize Napoleon's brother Joseph Bonaparte as King of Spain.

As he negotiated peace, Metternich also orchestrated a marriage between Napoleon and Archduchess Marie Louise, the daughter of Emperor Francis. Thus, he secured the survival of the Habsburgs by binding their bloodline to Napoleon's. Yet the Habsburgs would not have to fear Napoleon for long; his performance in the 1809 campaign suggested that he was past his military prime. In fact, the War of the Fifth Coalition would be his last triumph. Three years later, Napoleon's invasion of Russia would end in disaster, leading all of Europe to finally unite against him in the War of the Sixth Coalition (1813-1814).