The Battle of Wagram (5-6 July 1809) was one of the largest and bloodiest battles of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). It resulted in a pyrrhic victory for French Emperor Napoleon I (r. 1804-1814; 1815) whose army crossed the Danube River to defeat Archduke Charles' Austrian army. Wagram ultimately allowed Napoleon to win the War of the Fifth Coalition (1809).

Background

Ever since its defeat at the Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805), the Austrian Empire itched to exact revenge upon Napoleon and recover its status as a major power in Central Europe. In the three years that followed the battle, Austria bided its time as its army was modernized by Archduke Charles, brother of the emperor and commander-in-chief of the Austrian forces. Charles' reforms included a system of mass conscription through the Landwehr militia and a reorganization of the army into nine line and two reserve corps, copying the corps d'armee system that had contributed to Napoleon's success.

By early 1809, hundreds of thousands of French soldiers were off in Iberia fighting the Peninsular War (1807-1814) against Spain and Portugal. This greatly reduced France's military presence in Germany, an opportunity that Austrian Emperor Francis I was keen to take advantage of. Francis ordered his brother to prepare for war, and on 10 April 1809, Archduke Charles sparked the War of the Fifth Coalition when he invaded France's ally of Bavaria with 200,000 men. Napoleon was prepared; having noticed the build-up of Austrian forces, the French emperor had raised a new Army of Germany that consisted mainly of French conscripts and allied German soldiers from the Confederation of the Rhine. Since Archduke Charles' invasion got off to a slow start, Napoleon was able to launch a rapid counteroffensive. In the ensuing Landshut campaign, Napoleon's Army of Germany won a string of battles and forced Archduke Charles back across the Danube. Charles' retreat left the road to Vienna wide open, and Napoleon occupied the Austrian capital on 13 May.

Emperor Francis had evacuated Vienna before the French occupation, and Archduke Charles had rallied his forces and was currently sitting on the opposite bank of the Danube. Since all the major bridges across the river had been destroyed, Napoleon needed to build his own. He chose the floodplain of Lobau Island, south of Vienna, as the ideal location for his river crossing. By midday on 20 May, the pontoon bridge was completed, and the first elements of the French army crossed over to occupy the towns of Aspern and Essling. By the next morning, Napoleon had gotten 25,000 troops across the river, but efforts to get the rest of his army across were frustrated by the Austrians, who floated flaming barges down the river to punch holes in the French bridge.

At 1 p.m. on 21 May, Archduke Charles ordered an attack. The French were surprised by the sudden Austrian assault, and brutal fighting erupted around Aspern and Essling that lasted well into the night, at which point the French retained control of both towns. The battle resumed on the morning of 22 May; while the Austrian wings were embroiled in the struggle for the towns, French Marshal Jean Lannes led a charge against the vulnerable Austrian center. His attack came close to success but was stopped by the personal intervention of Archduke Charles, who led a spirited counterattack. As the day wore on, the French were pushed out of Essling, and the bridge was repeatedly damaged, preventing Napoleon from getting the rest of his army across. At 3 p.m., the French emperor decided to cut his losses and ordered a withdrawal to Lobau. The Battle of Aspern-Essling marked Napoleon's first major defeat in a decade and had cost him between 20-23,000 casualties including the irreplaceable Marshal Lannes, who was mortally wounded. The Austrians also suffered around 23,000 casualties but achieved victory, having denied the river crossing to Napoleon.

Preparations

Stunned by his defeat, Napoleon spent the day after the battle in an uncharacteristically lethargic haze. The emperor was wracked with indecision, leading him to summon one of the few war councils of his career. His marshals advised him to pull back far beyond the Danube to safely regroup and resupply, but Napoleon refused, mindful that such an action would require him to give up his glittering prize of Vienna. Instead, the emperor proposed that the army should stay in Vienna and wait for reinforcements before attempting to cross the Danube a second time; having learned from his mistakes, Napoleon was confident another crossing would succeed. His marshals were convinced, and the French proceeded to move 129 cannons onto Lobau Island, which would remain the focal point of the second crossing. Napoleon then focused his efforts on evacuating the 10,000 French wounded from the Aspern-Essling battlefield, ensuring they received the best treatment in Vienna's hospitals; in the words of historian David Chandler, it seemed that defeat had awakened in the emperor a "rare fit of conscience" (708).

The Austrians were equally sluggish. On the night of his victory, Archduke Charles declined to harass the French retreat and opted to remain on the east bank of the Danube over the heated protestations of his generals, who felt that they were wasting their opportunity to capitalize on their victory. The next day, Charles left two corps to keep an eye on French activity on Lobau Island and withdrew the rest of his army to the heights across the Russbach River. The archduke seems to have been waiting for the outbreak of a general German uprising against Napoleonic rule; while several rebellions did erupt in Tyrol, Westphalia, and Saxony, none of these reached the scale that Charles was counting on. Charles also hoped to be reinforced by his brother, Archduke John, who was leading the Austrian army in northern Italy. However, on 14 June, Archduke John was defeated at the Battle of Raab by the French Army of Italy led by Napoleon's stepson and viceroy of Italy, Eugène de Beauharnais.

As John led his bruised army to Pressburg (modern Bratislava) to regroup, Beauharnais led his 23,000 men to join his stepfather at Vienna. In the following days, more French units joined Napoleon's army; General Auguste de Marmont arrived with 10,000 men from Dalmatia, and Marshal Jean Bernadotte brought 14,000 Saxon troops. By 1 July, Napoleon had around 160,000 French and allied troops concentrated around Vienna, with many more still on the way. He decided the time was right to commence operations and began moving troops, weapons, and materiel onto Lobau Island. On 2 July, Napoleon moved several divisions to the north of Lobau, giving the impression that he meant to cross at the exact same spot as last time. Archduke Charles took the bait, moving his entire force to defend the bridgehead at Aspern and Essling. But by the next day, it became obvious that this was just a diversion, spooking Charles into abandoning this position and withdrawing back to the Russbach heights, overlooking the Marchfeld plain.

Crossing the Danube

On 4 July, Charles wrote to his brother John at Pressburg, telling him that a battle was imminent that would decide the fate of their dynasty. He urged John to march with all haste. Still, Charles made no effort to fortify the Russbach and seems to have been hoping to avoid a major battle there. By late afternoon, everything was ready for the French crossing; a bridge of 14 pontoons had been prepared and was guarded by a French flotilla with orders to stop any projectiles the Austrians might send to break up the bridge. At 9 p.m., French General Nicolas Oudinot moved his corps across, chasing away the scant Austrian outposts stationed on the opposite bank. Oudinot's men were soon joined by two more corps, led by marshals André Masséna and Louis-Nicolas Davout.

By dawn on 5 July, these corps had engaged the Austrian advance guard under Feldmarschalleutenant Armand von Nordmann. Under relentless fire from the French cannons on Lobau Island, Nordmann's troops had little choice but to give ground, offering minimal resistance to the advancing French corps; the exceptions were at Sachsengang castle and Gross-Enzersdorf, where Nordmann left just enough men to slow the French onslaught. However, a fresh barrage of French artillery was enough to clear the Austrians out of both positions. Another Austrian corps led by Feldmarschalleutenant Johann Klenau was ordered to delay the French advance, but Klenau's men were checked by the French cavalry, who used the open fields of the Marchfeld plain to their advantage. By 10 a.m., both Nordmann and Klenau were withdrawing to Charles' position behind the Russbach, and most of the French army had gotten across the river. Napoleon had amassed some 130,800 infantry, 23,300 cavalry, and 544 guns against Charles' 113,800 infantry, 14,600 cavalry, and 414 guns. The stage was set for the largest battle Europe had yet seen.

First Day: 5 July

Napoleon set up his headquarters on the knoll at Raasdorf, the only piece of elevated ground on the otherwise flat Marchfeld. From here, he organized Davout's corps on the right flank, Oudinot in the center, and Masséna on the left. Bernadotte's Saxons, Beauharnais's Army of Italy, Marmont's corps, and the Imperial Guard would form the secondary line. Napoleon's plan was for Davout to turn the enemy left flank while Oudinot and Bernadotte pinned the Austrians down, giving Beauharnais enough time to break through the enemy center. Charles, meanwhile, held his position on the heights, anxiously awaiting the arrival of Archduke John.

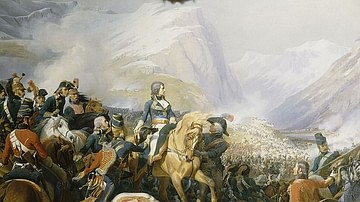

The French advance began at 1 p.m.; tens of thousands of troops pushed through waist-high cornfields across a 25-kilometer (16 mi) wide front. By 5 p.m., the French army had crossed the Marchfeld and was drawn up in an arrowhead formation across from the Russbach; Davout, Beauharnais, and Oudinot were facing the middle of the river with a combined 110,000 men. Bernadotte's Saxons had seized the vital town of Aderklaa, the possession of which could split the Austrian army in half. At 7 p.m., Napoleon ordered a general assault on the Austrian position, telling his marshals to "give us some music before nightfall" (Roberts, 519). Rather than a massive, coordinated assault, each French corps ended up making isolated attacks, allowing the Austrians to repel each one sequentially.

Oudinot's men were the first across the Russbach. They attacked the Austrian II Korps under Prince Hohenzollern near the hamlet of Baumersdorf but were soon driven back after suffering heavy losses. Beauharnais' Franco-Italian troops, on Oudinot's left, made some initial progress but were checked by an influx of Habsburg troops led by Archduke Charles himself. When some of Beauharnais' reserves accidentally fired on the Italian troops in the smoky confusion, the Italians panicked and fled; their disorderly retreat was stopped only when they came face-to-face with the bayonets of Napoleon's Imperial Guard.

That left Bernadotte's Saxon troops, who did not begin their assault on the village of Wagram until 9 p.m. The onset of darkness added to the usual battlefield chaos, and the Saxons were unable to progress beyond the town. The uniforms of the white-coated Saxons resembled those of the Austrians, causing several instances of friendly fire before Bernadotte ordered a withdrawal to Aderklaa at midnight. Bernadotte, whose rivalry with Napoleon had lasted for years, blamed the emperor for the failure, noisily ranting that "had he [Bernadotte] been in command, he would have forced Charles…to lay down his arms almost without combat" (Chandler, 719). This rant was reported back to Napoleon, who did not take it kindly.

Davout, noticing the failure of the other French assaults, decided against mounting his own, and the first day of battle came to an end. Despite the bungling of the evening assaults, Napoleon was quite pleased with the progress of his army. Confident that the next day would bring him a victory, the emperor spent the night in a roadside encampment, sleeping beside his troops and a pile of drums. Archduke Charles was also confident that he would secure a victory; he still possessed the high ground, half his army had not yet been engaged, and he still expected Archduke John to arrive with 12,000 reinforcements. Thus, spirits were high in both camps as, in the words of a German surgeon at the battle, “night fell, spreading its somber wings over the two armies. The silence of death reigned over all” (Gill, 52).

Second Day: 6 July

The second day of battle began at 4 a.m. when the sounds of musket fire could be heard on the French right flank; Davout's corps was under attack by the 18,000 men of the Austrian IV Korps under Prince Franz von Orsini-Rosenberg, with Nordmann's battered advance guard in support. Though Davout was caught off guard, his III Corps was the best disciplined in the French army and masterfully held its ground until Napoleon could rush over reinforcements. By 6 a.m., Rosenberg's men were retiring back across the Russbach. Davout pursued and began preparing an assault on the town of Markgrafneusiedl. But no sooner had this crisis been averted than Napoleon received news of another; between 3 and 4 a.m., Bernadotte had abandoned the vital position of Aderklaa without a fight. Napoleon was furious, especially after he learned that Aderklaa had since been occupied by the Austrian I Korps.

Bernadotte and Masséna were ordered to retake Aderklaa, which was briefly accomplished before Archduke Charles flung fresh regiments of grenadiers into the fray. Bernadotte rode ahead to rally his men and crossed paths with Napoleon. Still bristling at Bernadotte's remarks the previous night, Napoleon did not miss his chance to taunt the marshal: "Is this the maneuver by which you were going to make the archduke lay down his arms? A bungler like you is no good to me" (Roberts, 522). The emperor promptly removed Bernadotte from his command, ordering him to quit the army within 24 hours. Meanwhile, a division of Franco-Hessian troops swept through Aderklaa with shouts of “Vive l'Empereur!”, but they advanced too far and were ground down by a fresh Austrian counterattack. At 9:45 a.m., the French finally regained control of the town, but the French left wing was left in total disorder.

At 10 a.m., Klenau's VI Austrian Korps took advantage of the confusion, moving through the gap on the French left flank vacated by Masséna. Klenau swept aside the French artillery and advanced as far as Essling, threatening Lobau Island itself. This was the point of crisis. However, Klenau fatefully chose to halt his attack as he waited for fresh orders, allowing Napoleon time to maneuver. He sent Masséna's Corps southward on a quick march toward Essling; to buy Masséna time to execute this maneuver, Napoleon ordered the reserve cavalry to launch a series of near-suicidal charges against the Austrians massing near Aderklaa. Napoleon also assembled a 'grand battery' of 112 guns to pin down the Austrians and ordered Davout to commence his attack on Markgrafneusiedl. This quick thinking saved the day for the French; Klenau's men were packed too close together, providing easy prey for Napoleon's new battery and for Masséna's troops. The moment of crisis had passed.

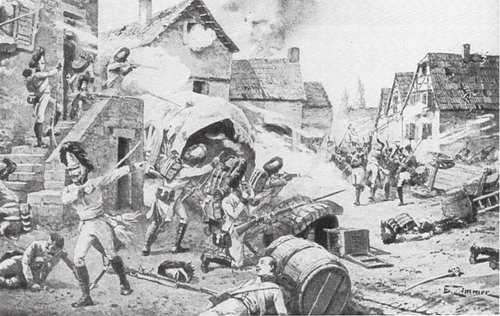

Davout, meanwhile, personally led the storming of Markgrafneusiedl. What followed was vicious house-to-house fighting, as the French heavily paid in blood for every yard gained. Davout's horse was killed from under him and his subordinate, General Gudin, suffered four wounds. Yet the French succeeded in taking the burning village and several Austrian counterattacks failed to dislodge them; Nordmann was killed leading one of these attacks, his body abandoned in a ditch by his fleeing men. When Napoleon saw through his spyglass that Davout had seized Markgrafneusiedl, he took a quick nap in his saddle, knowing that the battle was won. The only thing that could have changed this would be the appearance of Archduke John, but the archduke turned around as soon as he learned that his brother was on the verge of defeat.

To secure victory, Oudinot was instructed to storm the heights to the east of Wagram, with the main thrust entrusted to General Étienne Macdonald. Macdonald formed his 8,000 men into a huge hollow square, which made an easy target for the Austrian guns; before long, Macdonald's command was reduced to only 1,500 men. Frustrated, Napoleon sent Marmont in support, and the French slowly rolled the Austrians off the heights. By 2 p.m., Archduke Charles realized his brother was not coming and ordered a phased withdrawal. Napoleon neglected to pursue, still fearful that John might appear; it was not until the next morning that Napoleon realized there would be no third day of fighting. He had won.

Aftermath

Napoleon's victory came at a terrible cost; he had lost 32,500 men killed or wounded, or 24% of his army. These numbers include 40 generals and 1,822 junior officers. The Austrians suffered 37,156 casualties including four dead generals and 13 wounded senior officers. Despite the horrific carnage, the French celebrated their much-needed victory; "the whole French army got drunk the night after Wagram," recalled one French officer (Roberts, 525). Macdonald, Oudinot, and Marmont were awarded the rank of marshal after the battle. On 10-11 July, Marmont fought Charles in the inconclusive Battle of Znaim, which led Charles to ask for an armistice. The War of the Fifth Coalition was over; coming so soon after a defeat, victory at Wagram ensured that Napoleon's dominance of Europe would last for a little while longer.