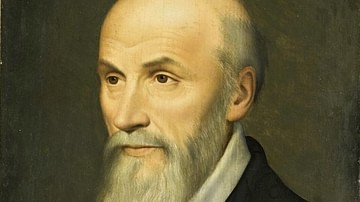

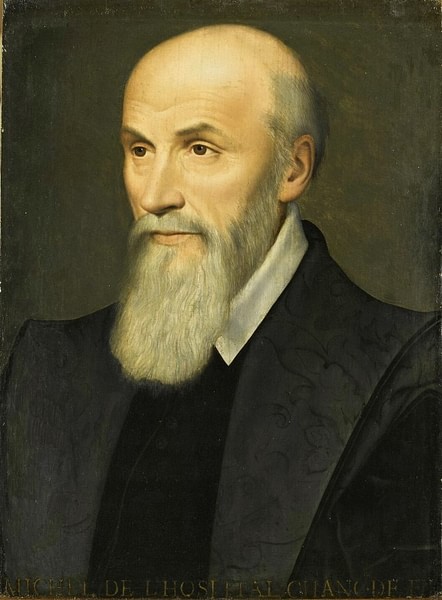

Michel de L'Hospital (also known as L'Hôpital, c. 1505-1573) was a French statesman who served during the reigns of four kings – Francis I, Henry II, Francis II, and Charles IX – as Councillor of Parlement (1537), Chancellor of the Duchesse de Berry (1550), the first president of the Chamber of Accounts (1555), and Chancellor of France (1560-1568).

At a time when "one king, one law, one faith" was the almost unanimous opinion of French people, L'Hospital advanced the concept of the separation of the state and church to free France from unending religious conflicts. He considered freedom of conscience as the first condition of social peace and worked tirelessly for peace between competing confessions.

Early Life

Michel de L'Hospital was born in 1505 or 1506 in the small town of Aigueperse in Auvergne. His father Jean was attached to the service of Charles de Bourbon, Constable of France, and sent his son to Toulouse for his studies. He only spent two years at Toulouse, but the atmosphere of violence that characterized the Protestant Reformation in France influenced what became a lifelong commitment to oppose all forms of intolerance.

During this time, the fortunes of Michel's father Jean were reversed by the troubles of Charles III, Duke of Bourbon (l. 1490-1527), viewed as a rival by King Francis I of France (r. 1515-1547). Bourbon was accused of a treasonous alliance with Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (l. 1500-1558). Jean was viewed as Bourbon's accomplice, leading to the confiscation of his property and Michel's arrest at Toulouse. Once released, he left for Italy to join his father in Milan. Jean lost everything at his patron's death when Charles de Bourbon was killed during the siege of Rome in 1527. Michel and his father went to Rome where Cardinal de Grammont persuaded both men to return to France. Michel's father was unable to recuperate his lands and left for Lorraine, where he died. In 1537, Michel married Marie Morin, the daughter of a high court official, the lieutenant-criminel of the Châtelet, with whom he had three daughters, and became a councillor in Parlement as part of the dowry.

Political Career

François Olivier (c. 1487-1560), Chancellor of France, recognized L'Hospital's qualities and entrusted to him matters of significant importance. In 1542, 1546, and 1547, he was sent to preside over special judicial sessions in the cities of Riom and Tours. His work in Parlement gave L'Hospital insight into the moral condition of France and stirred in him the desire to work toward reform in eliminating abuses. He failed to advance his career where he might have had more influence to bring about changes in social, religious, and political institutions. His influential friends at the court could not persuade an appointment from Francis I of France (r. 1515-1547), who saw in L'Hospital the son of a man who had allied himself with the treasonous Charles de Bourbon.

On 31 March 1547, King Francis I died and left the crown to his son Henry II of France (r. 1547-1559) who appointed L'Hospital ambassador to the Council of Trent. This mission provided him the opportunity to assess ecclesiastical questions and church and state relations. The new religious ideas of the Protestant Reformation had spread throughout Europe, and despite the Catholic Church's anathemas and persecution, there was the hope that religious unity could be re-established. The pope had promised a council in 1535 and delayed it as long as possible. He named two of his teenage grandchildren cardinals to ensure that the council would be beholden to him. L'Hospital was astonished at the small number of prelates in attendance and disillusioned when the high dignitaries of the Church, consulted by sovereigns on the best way to achieve religious harmony, served their nations' ambitions and personal interests.

After his return to France, L'Hospital was appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Berry, a region ruled by Marguerite de Navarre (l. 1492-1549), sister of Francis I and a proponent of the Reformation. L'Hospital considered that the years he administered the duchy were among his happiest. Although he conserved his title of councillor in Parlement, he was mostly exempt from participation in the affairs of litigation. It was here that his desire was strengthened for the development of the social order and respect for personal convictions.

As his influence grew, L'Hospital was entrusted by the French Court with important matters of state. After the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis ended the Italian Wars in April 1559, he accompanied Marguerite de Valois, Duchesse de Berry, daughter of Francis I, to sign the marriage contract with Duke Emanuele Filiberto, Charles V's nephew. L'Hospital's nomination as chancellor of France was prompted by the violence and executions that followed the failed Conspiracy of Amboise to kidnap King Francis II of France (r. 1559-1560) in March 1560. The conspiracy was the work of Huguenots and other malcontents who sought to remove the king from the influence of the House of Guise that had mobilized persecution against Protestants. The conspirators sought to obtain freedom of worship and the convocation of the Estates General to establish peace in the kingdom.

With the plot unmasked, the Duke of Guise succeeded in consolidating his power and was appointed lieutenant-général of the kingdom. Under the duke's authority, the ringleader of the conspiracy was killed and his co-conspirators were hunted down and massacred without due process. The queen mother, Catherine de' Medici (l. 1519-1589), was shocked by the savagery of the reprisals and realized that the unity of the kingdom was threatened. She wanted a moderate in government as an advocate for reconciliation and suggested that the king appoint L'Hospital. He became Chancellor of France on 6 May 1560 and remained in this position until 27 September 1568. Upon his appointment as chancellor, he supported the queen mother in seeking to counterbalance the power of the Guises.

The Colloquy of Poissy in 1561 under the direction of Chancellor L'Hospital presented the last opportunity for Catholics and Reformed believers to achieve religious tolerance and national unity in France. The chancellor had already affirmed at the Estates General in 1560 that he desired to relegate the terms 'Huguenots', 'Papists', and 'Lutherans' to the past and only conserve the name 'Christian'. In his address, he stated that conscience cannot be constrained and that constrained faith is no longer faith. However, the two faiths proved impossible to reconcile at the colloquy.

L'Hospital, assisted by Theodor Beza (l. 1519-1605), prepared the Edict of January in 1562 under Catherine de' Medici, which authorized Reformed worship for the first time under certain conditions. Opposition to the edict led to the persecution of Protestants in several places. The massacre of Huguenots at Toulouse in May and the destruction of churches in Vendôme and Meaux aggravated religious tensions. The chancellor, fearing for his life, pretexted an illness and remained away from the court, prompting the king to send Swiss guards to protect him from Parisian Catholics. Although he attended Mass regularly, L'Hospital's enemies accused him of masking his real beliefs. The papal nuncio and the ambassador of Spain pressured the court to replace him with someone more clearly on their side, and L'Hospital wrote to the pope to affirm his Catholic faith and desire for reform.

L'Hospital the Poet

During the first half of the 16th century, Christian humanists reflected on how religious poetry might best convey their evangelical values. Renaissance poets were looking for greater simplicity in translating the Christian faith placed at the center of human existence. L'Hospital reimagined poetry in the light of moderate evangelical commitments from a life and vision profoundly marked by the Christian faith. His writings included law and literature, politics, and poetry, revealing his commitments, hopes, and failures and became a strategic means of disseminating his convictions among diverse social circles.

His masterpiece Carmina was written from 1543 to 1573 and expressed the contradictions of his time in the struggle for religious reconciliation and justice. There are reflections on himself, society, human existence, and humanity's destiny. The epistles of Carmina trace his political fortunes as a figure of ethical and moral authority with political, moral, and literary reflections. Other poems develop ethical reflection, a meditation on the dangers of self-love and ignorance, a reflection on luxury and greed, and exhortations on the Christian life and moderation.

As Chancellor of France under Charles IX of France (r. 1560-1574), L'Hospital sought to neutralize and reconcile the hostility between Catholics and Protestants by affirming the necessity of religious tolerance. His attempts at national reconciliation ultimately failed, and he resigned from his position. The complexity of his thought has led historians to describe him as a crypto-Protestant, free thinker, or Christian rationalist. Perhaps the 18th-century biographer Louis-Jean Levesque de Pouilly best summarizes the life of the chancellor and poet Michel de L'Hospital:

[L'Hospital was] one of the most esteemed persons that France produced for whom the public good was always the object of his ambitions. L'Hospital desired to make his fellow citizens happier by making them more reasonable. (1)