Isaac I Komnenos was the Byzantine emperor from 1057 to 1059 CE. Although his reign was brief, he was known for being a capable and militarily astute general and emperor. As the first emperor to lead troops himself in battle in over 30 years, Isaac fended off the Pechenegs to the north while also instituting administrative reforms to prevent the Byzantine Empire from declining. His actions kept the status quo but it would quickly unravel under his successors.

Background

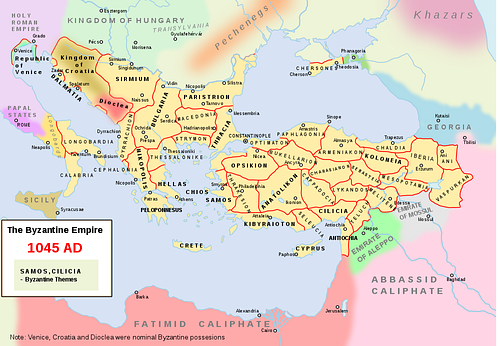

Isaac was born into one of the elite Byzantine military families of Anatolia, the son of Manuel Komnenos, one of Basil II's (r. 976-1025 CE) military commanders. Manuel died when Isaac was still young, and he and his brother John grew up in the Stoudios monastery in Constantinople. Isaac held a number of military commands and titles, including the honorific title of magistros, the position of doux (duke) of the recent Caucasian acquisitions of Vaspurakan and Iberia, and finally the position of stratopedarches, or commander of the eastern armies. Marrying Catherine, the daughter of Ivan Vladislav, the last tsar of the First Bulgarian Empire, Isaac then served as a commander from the reign of Basil II on, although the empress Theodora (r. 1055-1056 CE) removed him from the office of stratopedarches.

Taking the Throne

After the death of Theodora in 1056 CE, an administrative official, Michael VI (r. 1056-1057 CE) ascended the throne. Michael had no dynastic claim on the throne, the previous Macedonian Dynasty (r. 867-1056 CE) having perished with Theodora. Michael's reign was thus rife with coups. The first attempted coup, by Theodosios, cousin of Constantine IX Monomachos (r. 1042-1055 CE), was not successful. However, when Michael failed to promote a group of military commanders and instead publicly snubbed them, Isaac led the group in revolt at Easter 1057 CE. This group was comprised of leading generals who were descended from families that had been promoted by Basil II, including Katakalon Kekaumenos, Michael Bourtzes, and Constantine and John Doukas, among others. These were men from the military families that came to prominence during Basil II's reign. Their dislike for Michael's regime had likely already been simmering, seeing a stark contrast between their military prowess and the eunuchs and civilian politicians of Constantinople.

Isaac also had the highly respected veteran general Nikephoros Bryennios join his rebellion, which led valuable armies to join them in turn. However, Bryennios did not wait for Isaac's forces, was captured by Michael VI's men, and then blinded. With Bryennios unfit to rule, the rebellion decided that Isaac would be the most worthy candidate to replace Michael VI. On June 8, 1057 CE, the conspirators proclaimed Isaac emperor on his family estate in the Anatolian region of Paphlagonia, a fitting location for a rebellion by the landed military magnates of Anatolia. That summer Isaac's rebel forces defeated Michael's loyalists near Nikomedia and Isaac's rebellion approached Constantinople. Michael, fearing for his life, agreed to a deal where Isaac would be appointed Michael's co-emperor and they would rule together. But the Constantinopolitan populace was already turning in favor of Isaac and Michael's days were numbered without the support of the army or the people. The Patriarch of Constantinople, Michael Keroularios, persuaded Michael to abdicate in favor of Isaac and become a monk. Isaac had taken Constantinople without bloodshed and on September 1, 1057 CE, he was crowned emperor in the Hagia Sophia. It was the first successful military coup since Nikephros II Phokas (r. 963-969 CE) had taken the throne nearly a century before.

Issac was around 50 when he took the throne. Contemporary historian and government minister Michael Psellos described his character as twofold:

He was so gracious and pleasant in the one case, and in the other — why, even his face changed, his eyes flashed, and his brow, to put it metaphorically, hung threatening over the clear light of his soul like some dark cloud (Psellus 199).

Reign

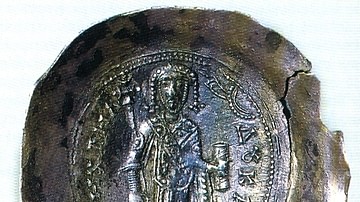

To signal the start of his reign, Isaac minted coins featuring himself wielding a drawn sword. This unusual design indicated that a military emperor sat on the throne once more – the first since Basil II – although it also could be seen as a sign of arrogance. He promoted his co-conspirators to top positions in the administration and military, and he made his brother John the domestikos, or head commander, of the western territories of the Byzantine Empire. Isaac also rewarded Keroularios for his support, including giving him broad oversight over church affairs.

Isaac's predecessors had lavished gifts on their supporters and had greatly inflated the imperial bureaucracy, leading to deficits in the budget. To remedy this, Isaac canceled a number of gifts and titles granted by previous emperors and decreased the rogai, the annual state salaries This naturally led to unpopularity, but since he had the army behind him, Isaac could operate from a position of strength, compared to his predecessors who frequently granted titles and rogai to avoid conflict.

Isaac also cut grants of public land to private individuals and especially targeted grants given to monasteries, since once these resources were in the hands of the church, they were effectively alienated since they could not be taxed. Naturally, the church was upset, as it had been when Nikephoros II Phokas did the same thing a century earlier. This possibly contributed to the deteriorating relations between Isaac and Keroularios. In part this was due to Keroularious acting like a kingmaker, even threatening that just as he had made Isaac emperor, he could unmake him too. Supposedly Keroularios even began to wear the purple boots that were the prerogative of the emperor alone. On November 8, 1058 CE, having had enough, Isaac had his elite Varangian Guard arrest Keroularios and exile him. It was normal enough for Byzantine emperors to remove patriarchs, since they theoretically only served at their pleasure. However, Keroularios would not resign and Isaac was preparing a synod to depose him when Keroularios died on January 21, 1059 CE. Isaac then had Constantine Leichoudes proclaimed patriarch.

In the first month of Isaac's reign, the Georgian lord Ivane, son of the Byzantine ally and Georgian strongman Liparit, had called in Turkish raiders to support him against the Byzantines. The Turks raided deep into Anatolia and even sacked the major city of Melitene. However, this force was destroyed when it was heading back through the Byzantine province of Taron in Armenia.

Isaac only led one campaign himself, and that was not against the Turks but against the Pecheneges and Hungarians. In 1059 CE, Isaac made a peace treaty with the Hungarians and attacked the Pechenegs, forcing all but one Pecheneg leader to surrender, and the one remaining leader was defeated. While this was a success, during Isaac's retreat, the army was caught in a large storm and many soldiers perished because of the floods and cold. Isaac himself was almost crushed by a falling tree, which would have been disastrous for the Byzantine Empire given that Isaac had not yet designated a successor. While the Pecheneg campaign was a victory, the deadly retreat limited its importance and, along with Isaac stepping down as emperor later that year, prevented the Byzantines from following up on their victory. The Pechenegs would remain the main threat to Byzantium from the north for another century.

Illness & Succession

After returning from the Pecheneg campaign, Isaac caught a cold while hunting and grew close to death. Isaac decided to appoint Constantine X Doukas, one of his co-conspirators back in 1057 CE, as his successor instead of any family members. This was in part because there were few good options. Isaac's only son, Manuel, had died before Isaac became emperor. His brother John's son, Alexios (the future Alexios I, r. 1081-1118 CE), was still just a toddler. This implies that there was not so much a coup as a realistic look at available options.

However, Psellos claimed that he had orchestrated the Doukas succession, possibly even against Isaac's better judgment. Isaac supposedly recovered, only for Psellos to publicly declare Constantine the new emperor and to leave Isaac left out. Isaac then retired to the Stoudios monastery, where he lived out the remaining six months of his life as a monk.

Legacy

Isaac is considered a successful Byzantine emperor, yet his succession was a disaster. After Isaac stepped down, the Empire continued to weaken in the face of the Seljuk Turks, Normans, and Pechenegs. If he had been able to pass the throne on directly to his relatives, the later Komnenian Dynasty (r. 1081-1185 CE), the future of Byzantium might have been different. The reality is that Isaac was merely a brief stop-gap in the slow decline of Byzantine political and military prowess over the course of the 11th century CE.