Michael Psellos (1018 - c. 1082 CE) was a Byzantine historian, writer, and intellectual. Michael acted as courtier and advisor to several Byzantine emperors, and he was the tutor of Michael VII. Writing between 1042 and 1078 CE, his texts combine theology, philosophy, and psychology, while his most famous work is the Chronographia, a series of biographies on emperors and empresses, which has proved an invaluable source on the Byzantine Empire of the 11th century CE.

Life & Works

Born in Constantinople in 1018 CE and given the name Constantine by his aristocratic parents, Michael later changed his name when he joined a monastery mid-career. Prior to that decision he successfully converted his early promise as a child prodigy when he was taught by John Mauropous (a future bishop), rose from the rather low starting point of a judge's clerk, and enjoyed a glittering career in the imperial administration in the capital of the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople. One of the court's intellectuals - and there were many at the time - Michael was an influential writer who combined both philosophy and theology in his letters and books which also encompassed a wide range of other subjects from rhetoric to law, medicine to history. He examined the psychological motivations of friendships and rulership, emphasised the importance of nature (physis) in human affairs and revived an interest in Neoplatonism. He was a member of the vibrant intellectual scene of Constantinople for decades and counted the city's patriarchs (bishops) John VIII Xiphilinos and Constantine Leichoudes as his friends.

Michael, although his long presence at court made him a perfect advisor for many short-reigning emperors, was not always a favourite in every ruler's court in his lifetime. There was a falling-out with the emperor Constantine IX (r. 1042-1055 CE) which led to Michael becoming a monk in a monastery on Mount Olympus. However, in 1045 CE, there was a reconciliation and Constantine made Michael the head of the refounded University of Constantinople. The scholar was given the impressive title of hypatos ton philosophon or Consul of the Philosophers. At the university, he focussed particularly on Rhetoric. Michael wrote widely on an impressive range of topics, for example, publishing his letters, a topography of ancient Athens, a summary of Homer's Iliad, a treatise on alchemy, seven eulogies, countless poems, and a comprehensive list of illnesses. Michael died around 1082 CE, although some scholars prefer a later date of 1096 CE.

Chronographia

Michael Psellos' most famous work is the Chronographia ('Chronicle') which covers the history of the Byzantine Empire from 976 to 1078 CE. It seemed that his time at court was mere preparation for his true vocation or, as the historian E. R. A. Sewter puts it in his introduction to his translation of the Chronographia, “the unusual triumphs of a political career are surpassed by his brilliance as a scholar” (14).

Michael's vivid descriptions of Byzantine emperors examine what might have led to the dramatic decline of the empire following the reign of Basil II (976-1025 CE). As an advisor to several emperors and both tutor and then chief minister to Michael VII (r. 1071-1078 CE), Michael was able to draw on personal experience and his privileged access to the imperial court to give a unique insight into Byzantine politics. The historian's influence at court is illustrated by his persuasion of Constantine X (r. 1059-1067 CE) to appoint the previously unfavoured John VIII Xiphilinos patriarch in 1064 CE. Indeed, Michael had contributed to Constantine's accession to the throne. For this reason, perhaps, the work is often a personal one, written in the first person and openly expressing the writer's views. It is also well to remember, though, that Michael, besides being a remarkable scholar, was also “self-seeking, conceited, sanctimonious and untrustworthy” (Norwich, 230), as is obvious from many purple passages of praise in his biographies, and so his history is rarely a wholly objective one.

The Chronographia does lack a military perspective and a wider view of international affairs, focusing as it does on domestic policies and the personalities of the rulers, and how these may have affected their decisions and successes or failures. There is a curious omission of names at times and a definite selection of facts. Michael was also a member of the ruling aristocracy, even if it was the intellectual branch, and the Chronographia does lack any discussion of the lot and role of the peasantry within the Byzantine state. Still, these omissions are not unique for writers of his time, and the work as a whole is one of the most important on Byzantine history that has been handed down to us. Further, Michael himself states in a private letter that the work is not intended to be comprehensive history nor to present the whole truth:

As I say, I am not making any attempt at the moment to investigate the especial circumstances of each event. My object is rather to pursue a middle course between those who recorded the imperial acts of Ancient Rome, on the one hand, and our modern chroniclers, on the other. I have neither aspired to the diffuseness of the former, nor have I sought to imitate the extreme brevity of the latter. (16)

The Chronographia covers the following 14 Byzantine rulers (all quotes are from the E. R. A. Sewter translation):

Basil II (r. 976-1025 CE)

Basil's character was two-fold, for he readily adapted himself no less to the crises of war than to the calm of peace. Really, if the truth be told, he was more of a villain in wartime, more of an emperor in time of peace. Outbursts of wrath he controlled and, like the proverbial “fire under the ashes” kept anger hidden in his heart, but, if his orders were disobeyed in war, on returning to his palace he would kindle his wrath and reveal it. Terrible then was the vengeance he took on the miscreant. (47-8)

Constantine VIII (r. 1025-1028 CE)

A person of decidedly effeminate character with but one object in life - to enjoy himself to the full. Since he inherited a treasury crammed with money, he was able to follow his natural inclination, and the new ruler devoted himself to a life of luxury. (53)

Romanos III (r. 1028-1034 CE)

He had a graceful turn of speech and a majestic utterance. A man of heroic stature, he looked every inch a king. His idea of his own range of knowledge was vastly exaggerated, but wishing to model his reign on those of the great Antonines of the past, the famous philosopher Marcus and Augustus, he paid attention particularly to two things: the study of letters and the science of war. Of the latter he was completely ignorant, and as for letters, his experience was far from profound. (63-4)

Michael IV (r. 1034-1041 CE)

I am aware that many chroniclers of his life will, in all probability, give an account different from mine, for in his time false opinions prevailed. But I took part in these events, and besides that, I have acquired information of a more confidential nature from men who were his intimate friends…For my own part, when I examine his deeds and compare successes with failures, I find that the former were the more numerous. (109 & 118)

Michael V (r. 1041-1042 CE)

A second peculiarity was the contradiction in the man between heart and tongue - he would think one thing and say something quite different. Men would often stir him to anger and yet meet with a reception of more than usual friendliness when they came to him…There were several examples, of men, who, at dawn the next morning, were destined by him to undergo the most horrible tortures, being made to share his table at dinner, the evening before…The man was a slave to his anger, changeable, stirred to hatred and wrath by any chance happening. (125-6)

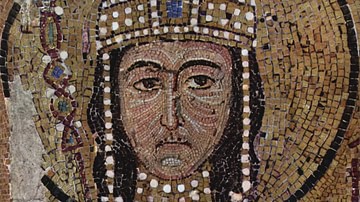

Theodora (r. 1042 CE & 1055-1056 CE)

Without the slightest embarrassment she assumed the duties of a man and she abandoned all pretence of acting through her ministers. She herself appointed her officials, dispensed justice from her throne with due solemnity, exercised her vote in the courts of law, issued decrees, sometimes in writing, sometimes by word of mouth. She gave orders, and her manner did not always show consideration for the feelings of her subjects, for she was sometimes more than a little abrupt. (261-2)

Zoe (r. 1042 CE)

Zoe was a woman of passionate interests, prepared with equal enthusiasm for both alternatives - death or life, I mean. In that she reminded me of sea-waves, now lifting a ship on high and then again plunging it down to the depths. (157)

Constantine IX (r. 1042-1055 CE)

In the emperor's case, the people were convinced that some supernatural power foretold him the future: because of this he had more than once shown himself undaunted in time of calamity. Hence, they argued, his contempt of danger and his utter nonchalance. (204)

Michael VI (r. 1056-1057 CE)

In the case of the aged Michael, the conferring of honours surpassed the bounds of propriety. He promoted individuals, not to the position immediately superior to that they already occupied, but elevated them to the next rank and the one above that…His generosity led to a state of absolute chaos. (275-6)

Isaac (r. 1057-1059 CE)

When dealing with ambassadors he pursued no set policy, except that he always held converse with them dressed in the most magnificent apparel. On those occasions he poured out a flood of words, more abundant than the rising Nile in Egypt or Euphrates splashing against the shores of Assyria. He made peace with those who desired it, but with the threat of war if they transgressed so much as one term of his treaty. (306)

Constantine X (r. 1059-1067 CE)

He was a keen student of literature and a favourite saying was this: 'Would that I were better known as a scholar than as emperor!' (344)

Eudokia (r. 1067 CE)

Her pronouncements had the note of authority which one associates with an emperor. Nor was this surprising, for she was in fact an exceedingly clever woman. On either side of her were the two sons, both of whom stood almost rooted to the spot, quite overcome with awe and reverence for their mother. (345)

Romanos IV (r. 1068-1071 CE)

With his usual contempt of all advice, whether on matters civil or military, he at once set out with his army and hurried to Caesarea. Having reached that objective, he was loath to advance any further and tried to find excuses for returning to Byzantium. (354)

Michael VII (r. 1071-1078 CE) - an unfinished biography.

I must first beg my readers not to look upon my version of the man's character and deeds as exaggerated. On the contrary, I shall hardly do justice to either. As I write these words, I find myself overcome by the same emotions as I often feel when I am in his presence: the same wonder thrills me. Indeed, it is impossible for me not to admire him. (367)