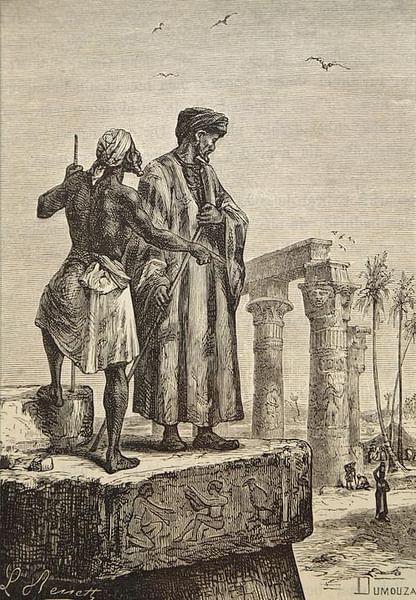

Ibn Battuta (l. 1304-1368/69) was a Moroccan explorer from Tangier whose expeditions took him further than any other traveler of his time and resulted in his famous work, The Rihla of Ibn Battuta. Scholar Douglas Bullis notes that “rihla” is not the book's title, but genre, rihla being Arabic for journey and a rihla, travel literature.

The book's actual title is A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling (Introduction, 1). Battuta kept no journal on his travels and his Rihla was composed from memory and embellished upon by the scholar Ibn Juzay al Kalbi (l. 1321-1357) between c. 1352-1355.

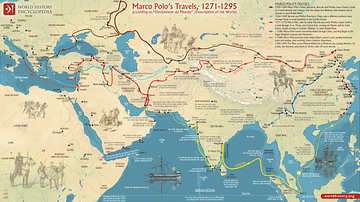

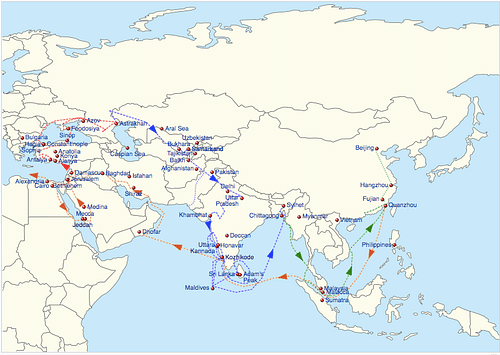

Leaving home at the age of 21, Ibn Battuta traveled the Islamic world and Far East of the 14th century, covering 75,000 miles (120,000 km) between 1325 - c. 1352, visiting 40 countries and crossing three continents. According to Bullis, “it would have worked out to a bit under 11 kilometers (7 mi) a day for almost 11,000 days” (Part I, 1). After he completed his travels, he returned home and dictated the tales of his adventures to Ibn Juzay. Little is known of his life afterwards. His now-famous work was almost unknown until the 19th century when German and English scholars brought it to world attention.

Early Life & Pilgrimage

Ibn Battuta was born in the medina (non-European quarter) of Tangier, Morocco, 25 February 1304. His full name, as given in the Rihla, was Shams al-Din Abu'Abdallah Muhammad ibn'Abdallah ibn Muhammad ibn Ibrahim ibn Muhammad ibn Yusuf al-Lawati al-Tanji ibn Battuta and all that is known of his family comes from the Rihla which records references to his education and provides his lineage.

He seems to have gone by the name `Shams al-Din' in his lifetime. He came from an educated background, a family of qadis (judges) and was devoted to his religion. He memorized the Quran and, as he reports, would sometimes recite it in its entirety twice a day during his travels. In June of 1325, he felt it was time to go on his first pilgrimage to Mecca and writes:

I set out alone, having neither fellow-traveller in whose companionship I might find cheer, nor caravan whose part I might join, but swayed by an overmastering impulse within me and a desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit these illustrious sanctuaries. So I braced my resolution to quit my dear ones, female and male, and forsook my home as birds forsake their nests. My parents being yet in the bonds of life, it weighed sorely upon me to part from them, and both they and I were afflicted with sorrow at this separation. (2)

Initially, he set himself only to accomplishing the pilgrimage and does not seem to have entertained any thoughts of going further than Mecca. He traveled across North Africa to Tunis where, upon entering the city, he records his feelings of loneliness and homesickness:

Townsfolk came forward on all sides with greetings and questions to one another. But not a soul said a word of greeting to me, since there was none of them that I knew. I felt so sad at heart on account of my loneliness that I could not restrain the tears that started to my eyes and wept bitterly. (4)

He was consoled by a fellow-pilgrim who introduced him to other educated men and found lodging for him at the College of the Booksellers. He left Tunis for Alexandria, Egypt in the company of a caravan for protection on the road (a strategy he would often employ throughout his travels). In Alexandria, he met a devout mystic named Burham al-Din who prophesied that he would visit Sind (Pakistan), India, and China and would enjoy the hospitality of al Din's three brothers who lived in those regions.

Later in Alexandria, while staying with Sheik al-Murshidi, Ibn Battuta had a dream in which he was carried by a great bird to Mecca but then beyond to lands he had never thought to see. The Sheik interpreted this dream for him as a sign that he would successfully reach Mecca but that his travels would take him much further. These experiences in Alexandria caused Ibn Battuta to re-think his original plan of returning home after the pilgrimage and he began to consider travel simply for its own sake, valuing the journey over the destination.

From Alexandria he went to Cairo and from there moved on through Palestine and Syria toward Mecca. Of his travels in Palestine, he writes, “I visited Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus. The site is covered by a large building; the Christians regard it with intense veneration and hospitably entertain all who alight at it” and, upon reaching Jerusalem, marvels at the Al-Aqsa Mosque, writing, “the sacred mosque is a most beautiful building and is said to be the largest mosque in the world” (20). In Damascus, "the city which surpasses all other cities in beauty", as he writes, he records the generosity of the government and upper class in providing endowments to those less fortunate and for the development of various aspects of the city (29).

Battuta notes how there are religious endowments for the needs of the people which take care of everything from replacing broken ceramics (plates and water jugs) to education for the young. He describes the novel innovation of paved streets and sidewalks and the beauty of the architecture in the city. Arriving in Mecca in October 1326, Battuta carefully relates the experience of the Ka'ba as thousands of pilgrims surged around the center of the world, where the celestial realm intersects with the kingdoms of the earth.

Further Travel

With the pilgrimage concluded, Battuta could now return home but, as scholar Ross E. Dunn observes, “He was no longer traveling to fulfill a religious mission or even to reach a particular destination” – he was now traveling simply for the love of travel (32). In 1326-1331, he crossed Persia to the Zagros Mountains, visited the city of Shiraz, famous at the time for its beauty and magnificent gardens, rode in the retinue of a Mongol ruler, visited Baghdad, and took ship to Yemen during which he survived a storm at sea.

The year 1331 or 1332 found him exploring Africa and then moving on to Anatolia (Turkey) where he escorted a princess to Constantinople and visited the Hagia Sophia. At some point between 1332-1333, upon finding that a ship to India would take too long to arrive, he set out on foot and crossed Central Asia to finally arrive in India almost a year after the time it would have taken the ship to bring him there.

In India, the Sultan of Delhi hired him as one the chief judges of the city. Historian Stewart Gordon writes, "Ibn Battuta's conversations with kings were, in a sense, the management seminars of the day; soon, Ibn Battuta was able to tell one king about another, information kings eagerly sought” (45). From India he visited China where he was again appointed a judge and moved on to the Maldives, again becoming a judge.

Here he complained, as he did elsewhere, about the way the women dressed, noting that they only wore clothing from the waist down and commenting, “when I held the office of judge among them, I was quite unable to get them covered entirely” (179). From the Maldives he went to Ceylon, Malaysia, traveled back through India, crossed the Sahara Desert, and made his way slowly through the Middle East.

In the course of his journeys he had married seven times, fathered a number of children, bought and sold slaves, had great riches and fine apartments, counseled kings and rode with princesses but had also traveled with nothing to his name but his trousers and the hope of finding some food, been shipwrecked, robbed, and had his life threatened by a Sultan.

Return Home

Finally, his thoughts turned to home and he traveled through Syria at the height of the plague in 1348, noting how death was all around him (he is recognized today as one of the first writers to record the plague in detail). Battuta detoured to Sardinia and traveled through Spain until he met up with a group of Muslims who were heading to Tangier. He arrived back in Morocco sometime in late 1348. Finding that his father and mother had died recently from the plague and that his friends were gone or dead, he set out again, returning to Spain and then taking a trip across to Timbuktu and the trading center of Gao only returning home again to Morocco in c. 1352.

He settled in the city of Fez where the Sultan Abu Inan heard his story and was so impressed that he asked it be written down. The Sultan either assigned the scribe Ibn Juzay al-Kalbi or Ibn Battuta chose him for the job (having met him earlier on his travels). Ibn Battuta narrated the tale of his journeys to Ibn Juzay and the result was the now-famous Rihla of Ibn Battuta. Following the dictation of his travels to Ibn Juzay, he vanishes from history but was most probably given a government post in the city by the Sultan. He died, probably in Fez, in either 1368 or 1369. The medina in Tangier is credited as his burial place and a site there as his tomb.

Critical Response to His Work

Although his work is generally accepted by scholars as factual and reliable and is certainly great reading (Ross E. Dunn calls it “worthy of an epic feature film”) some scholars have cited problems with details of the narrative which they attribute to scribal interference by Ibn Juzay, exaggeration by Ibn Battuta, or both.

The criticism claims that Ibn Juzay, as a court scribe, inserted passages from earlier writers or other accounts to supplement Ibn Battuta's memory. Ibn Battuta kept no travel journal and relied wholly on his memory in relating his tales. This reliance has troubled later scholars of his work who argue that he could not have remembered so clearly 30 years' worth of information. While this may be so, the historian Douglas Bullis writes:

When Ibn Battuta memorized the Qur'an, he embraced the collective assumption of the time that the mind can be relied on for accuracy just as our era relies on writing and microchips. Thus, in his descriptions, he was doing for his world something like what satellite television does for ours. (Part I, 4)

There is no doubt that Ibn Juzay, perhaps in an attempt to broaden or deepen descriptions, borrowed from earlier travel writers and, most notably, the work of Ibn Jubayr (1145-1217) a poet from Andalusia who traveled extensively and left behind the work which would inspire the genre of the Rihla. Passages from Battuta's Rihla describing cities such as Damascus, Mecca, and Medina are identical to those written over a century before by Jubayr.

This has no bearing, however, on the authenticity of Ibn Battuta's work. The value placed on originality in the creation of literature is a relatively recent phenomenon. Ancient readers and writers valued the story and what that story could give them; it did not matter who wrote it or how it was written.

What mattered to an ancient or medieval audience was the message and functionality of a written work and, of course, how good a story it was. To a medieval mind, Ibn Battuta's work would have served exactly the function Bullis describes above: to make the wide world a little smaller and a little more accessible to a reader back home while providing an entertaining story.

No modern-day scholar doubts that Ibn Battuta traveled as widely as he claims but some have questioned whether he could have visited all of the places he cites in his work. These charges will be familiar to anyone who has read ancient or modern criticism of Marco Polo's The Book of Marvels of the World (usually translated as The Travels of Marco Polo, c. 1300). As with Battuta's work, critics of Polo's Travels note how the poet Rustichello da Pisa (to whom Polo dictated his travels) inserted passages from his own Arthurian Romances as well as selections from earlier travel manuscripts to broaden the story.

Even so, scholars (including Dunn and Gordon) note that, while there are certainly passages which Ibn Juzay borrowed from other works, this in no way detracts from Battuta's account or his contribution to history, geography, and cultural understanding. If one were to remove all the passages which can be attributed to Juzay, one would still find a very impressive work of literature.

Conclusion

Although awareness of Battuta's travels is slowly becoming heightened in the present day, the Rihla of Ibn Battuta was unknown for centuries after his death. Whether inside or outside of the Muslim world, the tale of the great Moroccan traveler's journeys seems to have been forgotten shortly after it was set down. The historian A.S. Chughtai comments:

Ibn Battuta, one of the most remarkable travelers of all time, visited China sixty years after Marco Polo and in fact travelled 75,000 miles, much more than Marco Polo. Yet Battuta is never mentioned in geography books used in Muslim countries, let alone those in the West. Ibn Battuta's contribution to geography is unquestionably as great as that of any geographer yet the accounts of his travels are not easily accessible except to the specialist. (2)

While this situation is changing, it has been a long time coming. The manuscript was unknown in the west until the 19th century when a portion of the work was brought back by the German explorer Ulrich Jasper Seetzen. From between roughly 1818-1900 CE various translations were made of the Rihla until the Orientalist Sir Hamilton A.R. Gibb published a definitive English version in 1929.

Gibb had planned to translate the entire work in four volumes but only succeeded in completing three before his death in 1971. The complete English version of Ibn Battuta's Rihla only became available as recently as 1994 but the importance of the work has been steadily recognized since and, today, it is considered a classic of medieval travelogue.

Author's Note: Aspects of this piece first appeared in the article Ibn Battuta: The Most Famous Unknown Traveler in the World by Joshua J. Mark, published in Timeless Travels Magazine, Fall 2015.