Hippolytus is a tragedy written by Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE), one of the great Greek playwrights of the early 5th century BCE. As with many tragedies of the era, the central focus of Hippolytus is humanity's relationship with the gods. Hippolytus chooses not to pay homage to Aphrodite, the goddess of love; instead, he dedicates his life and love to the goddess of the hunt, Artemis. For his slight, his step-mother, Phaedra, is made to fall in love with him; a love that can never be returned. Innocently, Hippolytus rejects Phaedra' love and vows to remain away from the palace until his father, Theseus, returns. She becomes so distraught that she commits suicide, leaving a note accusing Hippolytus of rape. When Theseus returns, he banishes Hippolytus without a trial and prays that Poseidon kill him. Later, when Artemis reveals the truth, the remorseful Theseus is confronted with his dying son's body. In the end, Hippolytus forgives his father; something that one might find difficult to accept outside a play.

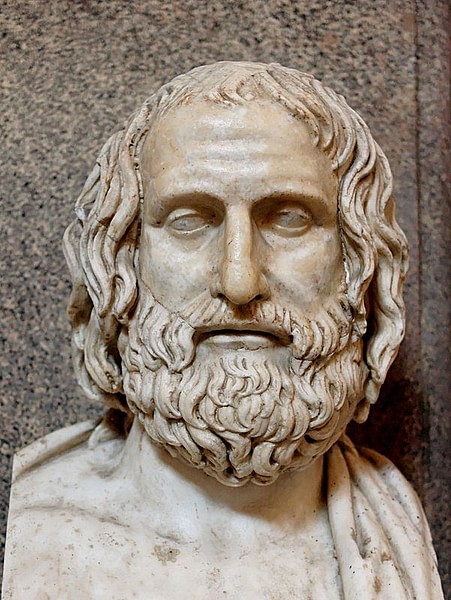

Euripides

Little is known of Euripides' early life. He was born on the island of Salamis near Athens to a family of hereditary priests. Although not as successful as fellow tragedians, Sophocles and Aeschylus, he participated in several dramatic competitions at the Dionysia beginning in 455 BCE but winning only four times and not winning his first victory until 441 BCE. Hippolytus was one of his most successful plays, providing him with one of his few victories. Of his over 90 plays, 19 have survived which is the most of any other author.

Athens was a depressing place during this time. It was a period of war between Sparta and Athens, which may have weighed heavily on the author. Although mostly avoiding involvement in the political and military life in Athens, he did serve on a diplomatic mission to Syracuse. Classicist Edith Hamilton in her The Greek Way quoted Aristotle's view of Euripides as the most tragic of the poets. She added that he felt the “pitifulness of human life” and no poet's work was “so sensitively attune as his to the still, sad music of humanity, a strain little heeded by that world of long ago” (205). This sadness may have been the cause of his leaving Athens in 408 BCE to live the remainder of his life at the court of King Archelaus of Macedonia.

The Background

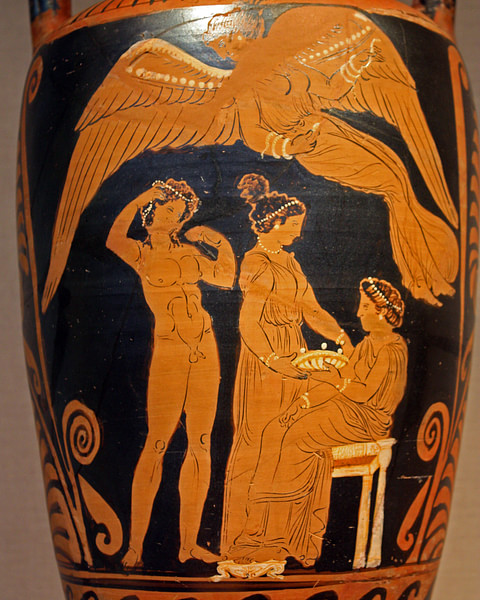

According to Thomas Martin's Ancient Greece, Greek plays often ended without any solution, leaving only suffering, turmoil, and death. And, as with other tragedies, the audience was already well aware of the myth and characters surrounding the play. In Euripides' version, Hippolytus is the illegitimate son of the Athenian hero and king Theseus and an Amazon queen. Unfortunately for the play's central character, Hippolytus, the goddess of love Aphrodite needed the young man to revere her, but he chose otherwise. As Moses Hadas points out in his Greek Drama, Hippolytus illegitimacy was a terrible stigma at the time, and he blamed and hated Aphrodite for his troubles. Instead of paying homage to Aphrodite, Hippolytus, therefore, dedicated himself to the virginal goddess of the hunt, Artemis.

Characters

The cast of characters for Hippolytus is rather small:

- Theseus

- Hippolytus

- Phaedra

- a servant

- a messenger

- the nurse

- a chorus of women

- a chorus of herdsmen

- Aphrodite

- Artemis

The Plot

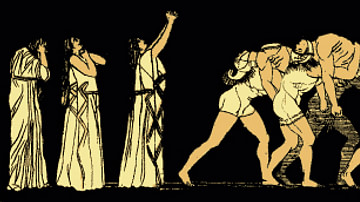

Outside Theseus' home in Troezen two large statues stand, one of Aphrodite and one of Artemis. The goddess of love Aphrodite speaks: “I am mighty among men and they honor me by many names” (Grene, 191). She adds that she will honor those who worship her in humility, but she warns that if they do not honor her she will lay them by their heels. She remarks that Theseus' son Hippolytus has blasphemed against her and worships Artemis instead. This dishonor angers Aphrodite, and she vows to punish him. Her plan is simple. She recognizes that his step-mother, Phaedra, loves him and “groans bitterness of heart.” (192). She will use this love to retaliate against Hippolytus. To accomplish her goal the queen must die. Theseus will learn of the matter and the tragic cause of her death, and he will slay Hippolytus with curses.

Renowned shall Phaedra be in her death, but none the less she must. Her suffering shall not weigh in the scale so much that I should let my enemies go untouched escaping payment of retribution sufficient to satisfy me. (193)

Hippolytus arrives from inside the house and lays a wreath at the base of the statue of Artemis:

Loved Mistress, here I offer you this coronal; it is a true worshipper's hand that gives it to you to crown the golden glory of your hair. (194)

His servant warns him not to slight Aphrodite, but the young prince replies she is not his god; some men choose one god while others choose another. The elderly servant exclaims that “The honors of the gods you must not scant, my son.” (196) As Hippolytus leaves, the servant prays that Aphrodite be forgiving for young men often speak foolishly.

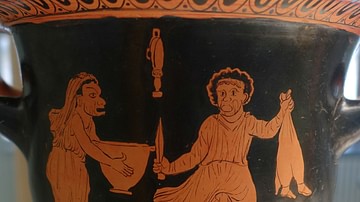

Shortly, a nurse and the queen Phaedra enter. The queen is obviously weak and asks the nurse to remove her headdress, for it is too heavy. The despondent wife of Theseus is restless and wants to go away to the mountains, to drink from a spring, to lie beneath the trees in a meadow, to find rest. The nurse is concerned and asks Phaedra what ails her. She responds:

O, I am miserable! What is this I've done? Where have I strayed from the highway of good sense? (201)

The chorus leader sees that the queen is in pain and asks the nurse for the cause of her ailment, but the nurse sidesteps the question and only says she has her troubles. The nurse continues to probe the queen to tell her of her ills. Desperately trying to find the reason, the nurse finally suggests that if she dies the queen's children will inherit nothing; it will all go to the illegitimate Hippolytus. Unmoved, the queen remains silent but cautions the nurse that she must never again speak Hippolytus' name. After the queen finally relents and says that someone she loves is destroying her. With her interest roused, the nurse continues to ply the queen for information. At last Phaedra admits she is in love with, of all people, her step-son Hippolytus:

… I believed that I could conquer love, conquer it with discretion and good sense. And when that too failed me, I resolved to die. (209)

The nurse advises the queen that she must tell her story, but she is chided. The nurse must hold her tongue and especially not tell Hippolytus, but, of course, the nurse does. Realizing the nurse has gone against her wishes, the queen says:

She loved me and she told him of my troubles, and so has ruined me. She was my doctor, but her cure as made my illness fatal now. (216)

Thinking she has done the right thing, the nurse begs Hippolytus to keep the information to himself. He replies, “My tongue swore, but my mind was quite unpledged” (217). He pledges to leave the house and not return until Theseus does. The angry Phaedra begs that Zeus raze the nurse from the world. She knows that Hippolytus will tell Theseus everything. The chorus leader asks Phaedra what she plans to do; she replies that she must die. She exits into the house.

Shortly, the nurse returns and says that the queen has hanged herself. The chorus wonders what they should do, whether they should cut her down. Theseus arrives and wonders why everyone is crying. He is told of his wife's death. He soon learns that the queen had left a note stating that Hippolytus had raped her.

He has dishonored Zeus's holy sunlight. Father Poseidon, once you gave to me three curses … Now with one of these I pray, kill my son this very day. (229)

The chorus leader begs him to reconsider. Refusing to recall his curse, Theseus chooses to banish Hippolytus. Poseidon will either honor his curse or Hippolytus will wander as a beggar. Hippolytus enters with his friends and asks his father why he mourns. He is told of Phaedra's death. Theseus speaks aloud:

Look at this man! He is my son and he dishonored my wife's bed! By the dead's testimony, he's clearly proved the vilest, falsest wretch. (231)

Hippolytus denies everything but Theseus refuses to listen and banishes him without a trial, for the letter is proof enough. Hippolytus is ordered away, and as he leaves he touches the statue of Artemis and says farewell.

A messenger arrives with tragic news; Hippolytus is dead - well almost dead.

Theseus, I bring you news worthy of distress for you and all the citizens who live in Athens' walls and boundaries of Troezen. …the balance that holds him [Hippolytus] in this world is slight indeed. (240)

Theseus calls upon Poseidon and thanks him. While Hippolytus and his comrades were combing their horses along the shore, waves crashed upon them. Now, the question remains: what to do with the body. Suddenly, the goddess Artemis appears. She tells Theseus that his wife's death was the fault of Aphrodite and the nurse's stratagems. Phaedra had tried to resist but failed. She says:

… your wife feared lest she be put to the proof and wrote a letter, a letter full of lies, and so she killed your son by treachery, but she convinced you. (245)

Theseus asks to see his son's body. Barely alive, Hippolytus is brought before his father. Artemis looks upon the fallen prince and tells him, “You are beloved by me” (248). She tells him that Aphrodite hated him for his temperance and disrespect, but she will be held accountable for her actions. Theseus speaks to his son, wishing that he could die in his place. Hippolytus frees his father of any guilt before he breathes his last.

Interpretation & LEgacy

According to Hadas, Hippolytus is a beautiful poem, both poignant and compassionate. Oddly, Hippolytus is rarely seen throughout the play, making only very brief appearances. Most of the early dialogue of the play is between the queen and her nurse. Knowing the ending of the play, it is difficult to have compassion for the queen. However, one must feel some sympathy for the young prince. Unknowingly, by rejecting his step-mother, he has sealed his fate. While considering him a victim, Hadas is careful not to call him a martyr.

In his book Antiquity, historian Norman Cantor said Hippolytus displayed the unbalanced personality of a tragic hero. He adds that all of the main characters sinned against the gods; Phaedra by means of her suicide, Hippolytus because of his excessive purity, and Theseus's through his anger. It is a tragic story of love, lies, and misfortune which would be read long after Euripides' death, influencing poets and playwrights such as the Roman Ovid and Seneca.