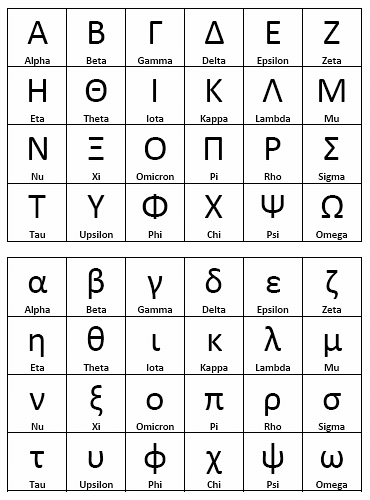

The Greek Alphabet developed from the Phoenician script at some point around the 8th century BCE. The earlier Mycenaean Linear B script, used primarily for lists and inventories, had been lost during the Greek Dark Age, and the technology of the written word remained unavailable until the invention of the alphabet, which influenced the later Latin script.

The basis for the writing system known as the 'alphabet' came from the Near East, specifically the Levant, but, as scholar Barry B. Powell, points out, these earlier systems were not the alphabet:

From an historical point of view, "alphabet" and "Greek alphabet" are one and the same. The Greek alphabet was the first writing that informed the reader what the words sounded like, whether or not he knew what the words meant. The word "alphabet" itself is Greek, formed from the Greek names of the first two signs in the series [alpha and beta]. Earlier writings, including such West Semitic writings as Phoenician and Hebrew, were in this sense not alphabets. All later alphabets, the Latin or Cyrillic or the International Phonetic Alphabet, are modifications of the Greek alphabet, having the same internal structure. (3)

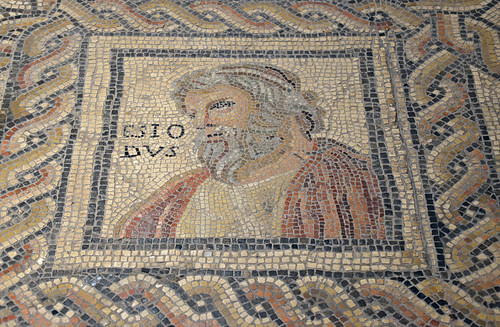

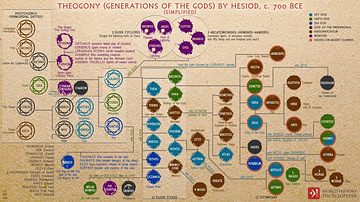

Unlike the Mycenaean Linear B Script, which seems to have served a primarily utilitarian function, the alphabet was quickly used in preserving the literary oral tradition by writing down the Iliad and the Odyssey (attributed to Homer) and religious traditions as recorded by Hesiod in his Theogony, all three dated to the 8th century BCE. New works were also created, however, such as Hesiod's Works and Days, and inscriptions such as the one from Nestor's Cup (also dated to the 8th century BCE), among the earliest extant examples of Greek writing.

From the 8th century BCE onwards, the Greek alphabet was used to produce all of the famous works of the civilization on topics ranging from astronomy and astrology to botany, biology, creative writing, literary criticism, history, the medical arts, philosophy, science, sociology, veterinary medicine, and zoology, among many others, standardizing knowledge and allowing for further developments. The Greek alphabet was adopted by the Etruscans and transmitted by them to the Romans who used it to develop the Latin script, which became the basis for modern alphabetic scripts.

Linear B & The Greek Dark Age

The Mycenaean Civilization (c. 1700-1100 BCE) developed over 100 urban centers across Greece and Anatolia and kept records through the writing system known as Linear B Script. Linear B developed from the Linear A Script of the Minoan Civilization (2000-1450 BCE), but as Linear A remains undeciphered, their relationship is unclear.

Linear B was a syllabic script consisting of over 80 signs and 100 ideograms. A syllabic script, as the name suggests, represents the syllables of a word through these characters – the signs providing phonetic and referential meaning and the ideograms the subject matter and quantity (or some unit of measurement). A line of Linear B would give the signs up front, the subject (sheep), and quantity (25) but could not convey a need for twenty-five sheep.

Consequently, the script was only used for official records of the Mycenaean palace complexes and inventory in trade. There is no written Mycenaean literature because they did not have a writing system capable of expressing complex thoughts or concepts, even though they clearly had such thoughts as shown through the archeological evidence of their religious practices.

The Mycenaean Civilization fell during the Bronze Age Collapse (c. 1250 to c. 1150 BCE), initiating the Greek Dark Age (c. 1200 to c. 800 BCE) during which Linear B was lost. However limited the script may have been, it still provided a written record of the activities of the people, which was no longer possible during the Dark Age. Reconstruction of daily life in ancient Greece during this period relies entirely on archaeological evidence or works from other civilizations of the Near East.

Origin of the Alphabet

At some point between 800-700 BCE, the alphabet was introduced to the Greeks by the Phoenicians (most likely through Phoenician traders), but how this happened is unclear. Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/413 BCE) provides the best-known version of the event:

The Phoenicians who came to Greece with Cadmus ended up living in this land and introducing the Greeks to a number of accomplishments, most notably the alphabet which, as far as I can tell, the Greeks did not have before then. At first the letters they used were the same as those of all Phoenicians everywhere, but as time went by, along with the sound, they changed the way they wrote the letters as well. At this time, most of their Greek neighbors were Ionians. So it was the Ionians who learnt the alphabet from the Phoenicians; they changed the shapes of a few letters, but they still called the alphabet they used the "Phoenician alphabet", which was only right, since it was the Phoenicians who had introduced it into Greece. (Book V.58)

Powell, among others, dismisses this account as "nascent historical thinking…seeking to place past human events in real time" (6) and mythologizing the event through the figure of Cadmus, the great Phoenician hero-prince who founded Thebes. Writers before and after Herodotus give their own versions of the birth of the Greek alphabet, some, like the Latin writer Gaius Julius Hyginus (l. c. 64 BCE to 17 CE), attributing it almost wholly to the work of the gods and Fates, but the general consensus is its Phoenician origin. Powell comments:

Phoenician writing consists of a signary of twenty-two syllabic signs, each of which designates a consonant plus an unspecified vowel (or no vowel). Of obscure origin, but usually thought to descend from Egyptian, the script was fully developed by 1000 BC, when it spread without differentiation to Hebrew Palestine and soon after to Aramaic-speaking Syria and northern Mesopotamia. The simple syllabary replaced, in many areas, the cumbersome logo-syllabic Akkadian cuneiform scripts, long supported by the ruling elite of Bronze Age civilization. (6-9)

Cuneiform, invented by the Sumerians c. 3500 BCE and refined c. 3200 BCE, had 600 characters in its simplest form. It is easy to understand, therefore, why a more concise writing system would have been welcomed and would, eventually, replace it. Scholars Christopher Scarre and Brian M. Fagan comment on the development of the system that became the Greek alphabet:

The idea of alphabetic components first appeared in inscriptions found in Sinai, known as Protosinaitic, and dated to c. 1700 BC. These took Egyptian hieroglyphics as a basis but used a small selection of the full range of hieroglyphic signs to form the letters of an alphabet. The language of the inscriptions was not Egyptian but Canaanite, and it was in the Levant that the subsequent development of the alphabet took place. By the eleventh century BC, a fully developed version of this early alphabet was being used by the Phoenicians. The Israelites and Aramaeans adopted and adapted the Phoenician alphabet in the ninth century BC, and the Greeks adopted it from Phoenician merchants in the eighth century. (222)

However the initial transfer of information took place, it is thought it involved a Greek who was well-acquainted with the Phoenician written script and was able to make whatever adjustments thought necessary to develop the script for use by the Greeks. This may have included adding vowels and two letters to bring the total number up to 24 from 22, or this development may have come later.

Early Use & Impact

Once the script was mastered, it was used to record far more than lists of inventory. The oral tradition of Greece, developed during the Dark Age and featuring tales of the creation of the world, the birth of the gods, and the adventures of great heroes, could now be committed to written form, and this seems to have happened fairly quickly after the alphabet was introduced to the Greeks. Scholar Thomas R. Martin comments:

Knowledge of writing was the most dramatic contribution of the ancient Near East to Greece as the latter region emerged from its Dark Age. The Greeks probably originally learned the alphabet from the Phoenicians to use it for record keeping in business and trade, as the Phoenicians did so well, but they soon started to employ it to record literature, namely, Homeric poetry. Since the ability to read and write remained unnecessary for most purposes in the predominantly agricultural economy of Archaic Greece and there were no schools, few people at first learned the new technology of letters. (58-59)

Those who write the stories, however, shape the culture, and it did not matter whether one could read the pages of Homer because one could hear the stories read, watch their recitation, and through this participation, however passive, absorb the cultural values encouraged by the literate social elite. Martin notes:

The ideas and traditions of this social elite concerning the organization of their communities and proper behavior for everyone in them – that is, their code of values – represented, like the reappearance of agriculture, basic components of Greece's emerging new political forms. The social values of the Dark Age elite underlie the stories told in the Iliad and Odyssey, two book-length poems that first began to be written down about the middle of the eighth century BC, at the very end of the Dark Age. (42-43)

At about this same time, the poet Hesiod composed his Theogony on creation, the birth of the gods, and their genealogy and, sometime after this, wrote the first autobiographical poem in Greek literature, Works and Days, invoking the gods to take his side against unjust judges and laws that favored his brother Perses over the author in a dispute regarding ownership of the family farm. Although earlier civilizations had produced autobiographical works, these were not available to the Greeks, as Powell notes:

What about the literature that went before, couched in the writings of the immemorially old, splendid civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia? These literate civilizations flourished 2,500 years before Homer and gave much to Hellas in technical and material culture. How much of their literate culture was transferred to Greece? The answer is "little or none." The Greek simply could not read the writings of pre-Greek peoples. (1)

The works of Homer and Hesiod, therefore, while not 'new' from a global historical perspective, were completely novel to the Greeks. The influence the Greek alphabet had on the development of Greek culture was enormous, even if, as noted, most of the population was illiterate during the Archaic Age. The alphabet introduced the people to worlds presented by writers they would never meet, and it allowed for endless possibilities of word combinations in shaping these worlds for a particular effect, sometimes the same effect: elevation, enlightenment, and understanding.

The Iliad and Odyssey are epic book-length poems, the Theogony a little over 1000 lines, Works and Days almost 900 lines, but among the earliest examples of the Greek alphabet is a three-line inscription on the drinking vessel known as Nestor's Cup which could be considered the first 'beer commercial' in history:

Who am I? None other than the luscious

Drinking cup of Nestor. Drink me quickly –

And be seized in lust by golden Aphrodite.(Cahill, 58)

On the simplest level, the inscription suggests a narrative still used in advertising in the present day – Drink this beer and get the beautiful woman – but by identifying the vessel as Nestor's cup it also invites the drinker to associate himself with Nestor, the wise king of Pylos from the Iliad and, by that association, with all the other great Homeric heroes, gods, and goddesses. Just as the Iliad and Odyssey might elevate the hearts and minds of the hearers, so might this inscription of only three lines.

The cultural impact of these works, which owed their existence to the alphabet, was immense. Scholar Thomas Cahill comments:

A writing system of some twenty-odd characters meant that anyone might learn to read, even a child, a woman, or a slave. What empowerment this implied! – especially when considered against earlier systems…One needed to know Hebrew well in order to read it confidently. If Hebrew was not your mother tongue, you would always be guessing which vowel sounds to supply between the consonants. But written Greek, because of the addition of vowels, required no subjective judgment or interpretation. It was completely objective, completely out there, completely distinct from the reader. Just as the simplicity of alphabetical writing made possible general access to literacy, which in its turn encouraged democratic give-and-take, the utter objectivity of the Greek alphabet encouraged the demystification of the world. (59)

Conclusion

As the alphabet allowed one to build on lessons of the past, it encouraged the development of philosophical, scientific, medical, religious, political, cultural, and social systems. In Greece, the concept of democracy was already understood and practiced during the Dark Age, but during the Archaic and Classical ages, it developed into a recognizable system of government. Prior to the alphabet, one could believe whatever one wanted to without difficulty, but, afterwards, one was required to reconcile one's beliefs with an objective standard of reality as presented by the written word.

Since the Greek alphabetic script was easier to learn than others, it encouraged greater literacy, broadened through the establishment of schools, resulting in a more cohesive society that recognized objective truths, even if they then argued over what those truths meant. It also led to a democratization of literacy. Although only the upper class could afford the tuition for formal education, anyone with the desire could learn how to read the Greek alphabet. Cahill comments:

A type of literacy that can be grasped easily by almost anyone will tend to spread some kind of proto-democratic consciousness far and wide, even if this is accomplished only in small steps over a very long period of time…A type of literacy that demystifies the act of reading, erasing for all time the aura of an unapproachable Sacred Brotherhood of scribes, wisemen, and potentates, will by its very nature tend to demystify additional realms of human experience. (60)

The Greek alphabet, later adopted by the Etruscans and then the Romans, became the basis for the modern-day alphabet and, so, the modern paradigm of what constitutes objective reality. Prior to the alphabet, a narrative concerning the life of the state or community might take many forms depending on the memory of the speaker and their particular interpretation; afterwards, stories became standardized, accepted as truth, and known as 'history.' Discoveries or novel ideas, whose transmission previously relied on one's proximity to the innovator, could now be understood over both distance and time, allowing for further development in multiple disciplines. Before the alphabet, there was only opinion; afterwards, there was fact.