The Despotate of the Morea was a semi-autonomous appanage of the later Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines retook part of the Peloponnese in Southern Greece in 1262 CE, but the Morea was only officially governed by semi-autonomous despots of the imperial Kantakouzenos and Palaiologos families starting in 1349 CE. The Despotate of the Morea would end up outlasting the Byzantine Empire itself, and the final part of the territory would not fall to the Ottomans until 1461 CE.

The Byzantine Morea

Following the loss of Constantinople to the Fourth Crusade in 1204 CE, the Byzantine Empire collapsed. Its territory was broken down into a variety of Byzantine and Latin successor states, and southern Greece went almost completely to the Latins, or Franks. The Peloponnese, that peninsula at the very southern end of Greece, went to the House of Villehardouin, which ruled the Principality of Achaea. For over 50 years, the Peloponnese was entirely in Latin hands.

In 1259 CE, William II of Villehardouin, Prince of Achaea (r. 1246-1278 CE), lost the Battle of Pelagonia against the emperor of Nicaea (soon to be the emperor of the restored Byzantine Empire after the capture of Constantinople in 1261 CE), Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259-1282 CE), and was captured. The terms of his release were the surrender of the castles of Monemvasia, Maina, and Mystras (aka Mistras) in southern Greece, in the Morea. In 1262 CE, the castle of Mystras, which would be of such great importance to the House of Palaiologos, was now Byzantine.

When it was first occupied, Mystras was an isolated Byzantine outpost in the midst of Frankish Achaean territory. The city of Lacedemonia was still in Frankish hands, and the Greek population of Lacedomonia soon flocked to Mystras, where they could be ruled as equal citizens rather than second-class members of society. A Byzantine expedition tried to recover the surrounding area but was pushed back by the Franks An Achaean army even besieged Mystras, but it was impossible to dislodge the Byzantine garrison. Meanwhile, Lacedemonia was practically deserted since the Greek population had moved to Mystras, and it was abandoned when the Franks retreated. Another city would not rise there until the 19th century CE when modern Sparta (or Sparti in Greek) was built. For the next seven centuries, Mystras was to be the social and political center of the region.

Over the next decade, the whole of that region, the vale of Sparta, came under Byzantine control. Threats and border skirmishes came from the kings of Naples and the princes of Achaea, but the Principality of Achaea gradually fell more and more into disarray until it was no longer a serious threat to the Byzantine possessions in the Peloponnese by the mid-14th century. Mystras was the center of this now secure Byzantine dominion. Monemvasia had originally been the provincial capital, but by 1289 CE, the Byzantine provincial governor had moved to Mystras.

The Kantakouzenos Despotate

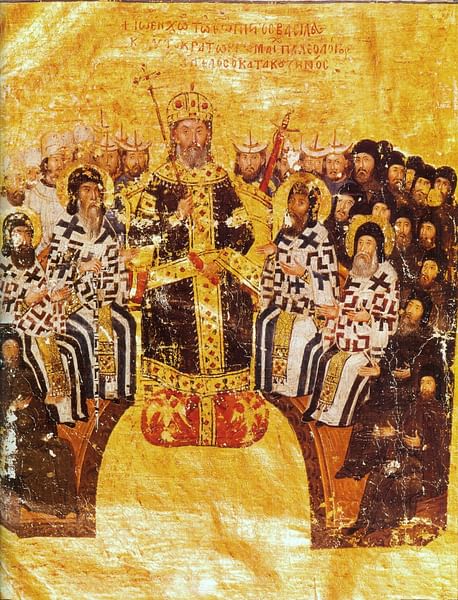

During the Byzantine civil war between John V Palaiologos (r. 1341-1391 CE) and John VI Kantakouzenos (r. 1347-1354 CE), the Byzantine possessions in the Peloponnese began to slip from centralized control, with local lords effectively operating outside of imperial rule. When the civil war was concluded, John VI Kantakouzenos, in 1349 CE, appointed his younger son Manuel Kantakouzenos to rule from Mystras under the title of despot. Mystras and the surrounding province were very much still under Byzantine control, but the long distance to Constantinople meant that Manuel effectively led an autonomous region and conducted his own policy and administration rather than those of his father. It is from this point that we can refer to the polity as the Despotate of the Morea, an autonomous unit in the Peloponnese that was part of the later Byzantine Empire.

Manuel concluded agreements with Venice and the Principality of Achaea, both to help bring his own autonomous landlords to heel and also to fend of the growing might of the Ottoman Turks. When a succession crisis emerged in Achaea in 1364 CE, Manuel involved himself in it and managed to take a few border towns for the despotate, but was then attacked in 1375 CE once the succession had been settled. However, Manuel generally tried to maintain good relations with his Frankish (or Latin) neighbors and even enjoyed a lively correspondence with Pope Gregory XI (r. 1370-1378 CE), which helped pacify his own Latin subjects.

Manuel's position inside the Byzantine Empire was put at risk, however, when his father, John VI, was deposed in 1354 CE. Matthew Kantakouzenos, Manuel's brother, tried to resist John V's rule, and, trying to broker a peace, the deposed John VI offered Matthew the Despotate of the Morea for peace. Peace was elusive, however, and civil war between Matthew and John V did break out, although in the eventual peace the Morea was not discussed. Meanwhile, John V had tried to replace Manuel with Michael and Andrew Asen as despots of the Morea, no doubt hoping to snuff out Kantakouzenos power. However, the people of the Morea supported Manuel, and eventually, Michael and Andrew gave up and went home to Constantinople. In 1361 CE, Matthew Kantakouzenos moved to Mystras, and although he initially expected the despotate as a former emperor, he was satisfied with being associated with Manuel's government. The former emperor John VI also visited Mystras on several occasions. Manuel enjoyed a successful tenure as despot until 1380 CE when he died peacefully.

His brother Matthew succeeded him but had long lost interest in power and was willing to step aside if a new despot was appointed. That was soon the case, as yet another Byzantine civil war was patched up only through dividing the Byzantine Empire between the members of the Palaiologos family, with John V remaining in overall control. To his son, Theodore Palaiologos, went the Despotate of the Morea. John VI, who had helped conclude this Palaiologos family peace, went to Mystras to inform Matthew and help him govern. However, by the time Theodore arrived, the province was in revolt under Matthew's son, Demetrios, who had expected to inherit the Morea. Thankfully for Theodore, Demetrios died in 1383 or 1384 CE, and the revolt died with him. The Kantakouzenos Dynasty was gone, the Palaiologos Dynasty would now be the despots of the Morea until the end.

The Palaiologan Despots

The reign of Theodore I Palaiologos (r. 1383-1407 CE) was much like that of his predecessors in the sense that the Despotate of the Morea operated autonomously of the Byzantine emperor in Constantinople. This was especially true during the final years of John V's reign, although Theodore was quite loyal to his brother Manuel II Palaiologos (r. 1391-1425 CE) when he came to the throne. Upon arriving in the despotate, Theodore first had to contend with Demetrios Kantakouzenos' revolt; although Demetrios died, this was not until after Theodore offered the city of Monemvasia to Venice for aid. The Greeks in Monemvasia, which included some of Demetrios' most staunch supporters, refused to let the Venetians in, and Monemvasia stayed in Byzantine hands.

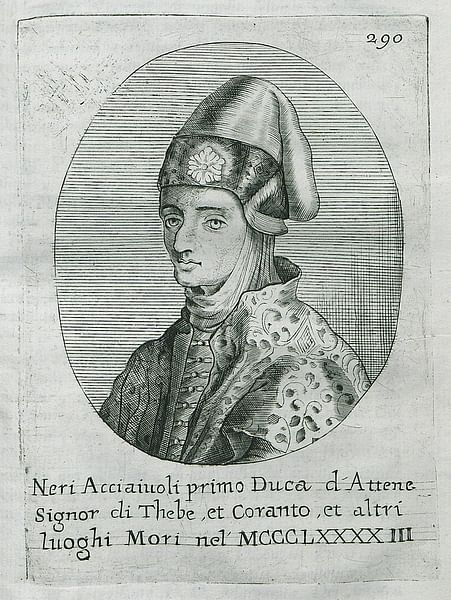

But while Manuel had sought peace with his neighbors, Theodore engaged in active diplomacy and war. The weakened Principality of Achaea was at this point effectively ruled by the Navarrese Company, a group of mercenaries, and Theodore managed to conquer border towns from them. He concluded an alliance with Nerio I Acciaioli, the lord of Corinth, who would soon take the Duchy of Athens for himself. In 1388 CE, Theodore and Nerio took the cities of Argos and Nauplio before the Venetians could occupy them, although the Venetians pushed Nerio out of Nauplio and Theodore was eventually forced to turn over Argos to the Venetians in 1394 CE.

However, Argos was ceded not because of Venice but because of the growing danger on the horizon: the Ottoman Turks. The Ottomans had crushed the Serbs at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 CE and followed up on their victory by occupying Thessaly. In 1394 CE, Theodore was forced to go to Serres and bow before Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I (r. 1389-1402 CE). When Theodore left without the sultan's permission, a Turkish army marched across the Isthmus of Corinth and into the Peloponnese for the first time in 1395 CE. The raid devastated Arkadia and Turkish marauders stayed even after the army had returned home.

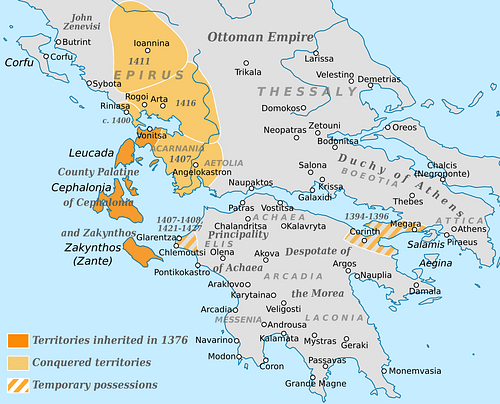

After the Ottoman army had gone, Theodore attacked the city of Corinth, which was held by Carlo I Tocco (r. 1376-1429 CE), Count of Cephalonia, who had inherited it from Nerio I Acciaioli. By the end of 1395 CE, Carlo decided to cede the city to Theodore. Now in control of Corinth, Theodore decided to restore the ancient Hexamilion Wall, a defensive wall that stretched the length of the Isthmus of Corinth. The idea was that with a great fortification protecting the Peloponnese, the Peloponnese would effectively be a fortress. However, the wall could not stand against a 50,000-man strong Ottoman army, which broke through the fortifications and pillaged through the Peloponnese in 1396 CE.

In desperation, Theodore sold Corinth to the Knights Hospitaller in 1400 CE to defend the peninsula against the Ottomans. Soon, the Hospitallers wanted more territory, including Kalavryta and Mystras itself. Theodore despondently agreed, and Kalavryta was handed over, but the citizens of Mystras practically slaughtered the Knights' representatives when they came to take control of the city. In 1404 CE, a new treaty was hammered out that gave the Knights the city of Salona, to the north of the Isthmus of Corinth, in exchange for Corinth, Kalavryta, and the Knights' claim on Mystras. This remarkable treaty was mostly the work of Emperor Manuel II; Theodore was by this point quite ill and died three years later.

Manuel had planned for the succession. He had sent his second son, Theodore II Palaiologos (r. 1407-1443 CE), to live in Mystras, prepared to take up the governorship of the Morea when his uncle breathed his last. In 1408 CE, Manuel visited Mystras himself to ensure that the administration was in good order and the local notables still viewed Byzantine rule favorably. Theodore was still but a boy at this time, but the Ottoman Empire was wracked by civil war following the disastrous Battle of Ankara against Timur the Lame (aka Tamerlane) in 1402 CE. The eventual victor, Mehmed I (r. 1413-1421 CE), had Byzantine support and respected Manuel II as a father. Thus for a period of nearly 20 years, the Byzantine Empire was allowed to breathe in peace.

In 1415 CE, Manuel went to the Morea to officially make Theodore the despot now that he had come of age. In addition, he went to the Isthmus of Corinth to examine the defenses and ordered a new, stronger Hexamilion wall built. But Manuel had to impose a tax on the Morean aristocrats; a rebellion by some of them was swiftly put down and the tax was imposed. That same year, Centurione II Zaccaria (r. 1404-1432 CE), the Prince of Achaea, came to Mystras to bow as a vassal of the Byzantines.

Theodore's court was a center of intellectualism. Theodore himself was considered one of the great mathematicians of his day, and scholars from the Greek world gathered in Mystras. While the days of Byzantium were numbered, Mystras served as a vibrant center of learning where philosophers, religious scholars, and other intellectuals gathered under the patronage of Theodore and his wife, Cleope Malatesta.

In 1423 CE, the long peace with the Ottomans was shattered when John VIII Palaiologos (r. 1425-1448 CE) backed a rival to the Ottoman throne. Theodore had been unsuccessful at maintaining troops to adequately man the Hexamilion Wall, and Ottoman troops easily broke through, raiding through the Peloponnese once more.

Meanwhile, the small states of Greece continued to war with each other. A series of skirmishes were fought between Centurione II and Theodore. In 1423-1424 CE, the Duchy of Athens tried to take Corinth. The greatest danger was the invasion of Carlo I Tocco, who had by this time consolidated his rule over all of Epirus. Carlo purchased the Achaean city of Clarentza in 1421 CE, effectively subordinated the Principality of Achaea to his rule, and attacked the Morea. John VIII had to come in person to push Carlo back, and in 1426 CE Carlo was decisively defeated in a naval engagement off the coast.

With the Byzantine Empire shrinking by the year, little was left besides the environs of Constantinople itself and the Peloponnese by 1427 CE. Therefore, the Morea was divided between three of John's brothers: Theodore remained the despot in Mystras; Constantine received Clarentza, the northern shore, and the Mani Peninsula; and Thomas received Kalavryta. Constantine captured the Latin-held city of Patras in 1429 CE, and Thomas marched on the remnants of the Principality of Achaea. Centurione offered his daughter in marriage to Thomas, giving him most of the Principality. The few possessions he maintained for himself were captured by Thomas in 1432 CE after Centurione's death. Now the whole of the Peloponnese, minus four cities held by the Venetians, was Byzantine.

The territories of the three brothers were realigned, with Constantine ruling the north from Corinth, Thomas ruling the west from Clarentza, and Theodore still ruling the southeast from Mystras. Although in reality, Theodore was merely first in precedence among the brothers, Mystras remained the political and cultural center of the despotate. The brothers, despite effectively going their own ways, were generally at peace with one another, although skirmishes broke out between Theodore and Constantine in 1435 CE when the question of who would succeed John as Byzantine emperor arose. In 1443 CE, Constantine became the despot of the Morea (r. 1443-1449 CE), while Theodore was sent to rule the appanage at Selymbria near Constantinople. Theodore's long tenure in the Morea had been difficult but successful, and the land was prosperous when he left.

The Final Years

Constantine immediately reorganized the administration of the Morea, appointing his friends as trusted governors and reinstating the privileges of the nobility to convince them to contribute to the reconstruction of the Hexamilion wall. Taking advantage of the Crusade of Varna distracting the Ottomans, Constantine captured Thebes and Athens in 1444 CE, forcing the Duke of Athens to do homage to him. The following year, Constantine marched further north into Phocis and the Pindos Mountains, capturing territory from the Turks and accepting homage from the local Vlachs. In 1446 CE, the Ottomans attacked Greece and advanced on the Hexamilion wall. Although the defenses were well manned, with the aid of their cannon, the Ottomans breached the walls on 10 December 1446 CE. Ottoman forces ravaged the Morea once again, supposedly selling 60,000 of the peninsula's inhabitants as slaves. Constantine and Thomas were forced to submit to the sultan, the Hexamilion wall was to be left in ruins, and they were forced to pay tribute to the Ottomans.

John VIII died at the end of 1448 CE, and Constantine was to be crowned the next, and final, Byzantine emperor. However, he was not crowned in Constantinople but held a ceremony in Mystras on 6 January 1449. Ironically then, for the accession of the final Byzantine emperor, it was not the people of Constantinople who would gather and proclaim him the descendants of Caesar and Augustus, but the people of Mystras, where he had ruled for the past six years.

Meanwhile, the Despotate of the Morea was handed over to the brothers Thomas and Demetrios. Thomas ruled the northwestern half, including Clarentza, Patras, and most of the territory he had previously ruled. Demetrios would rule the southeastern half, including Mystras. The two brothers did not get along well, and a territorial dispute in 1451 CE had to be settled by the Ottomans. In 1452 CE, in preparation for the final assault on Constantinople, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II (r. 1444-1446, 1451-1481 CE) sent an army to raid the Morea once again. It only retreated when a section of the army was caught in a narrow defile and slaughtered. Constantinople fell to the Ottomans on 29 May 1453 CE, with the final emperor, Constantine XI, dying heroically in the fighting. The whole Byzantine world, indeed the whole Christian world, mourned the loss of the queen of cities.

With the loss of Constantinople, the days of the Despotate of the Morea were numbered. The local Albanians rose in revolt under John Asen Centurione and Manuel Kantakouzenos. The rebellion was only put down with the help of the Ottomans, who demanded an outrageously large amount of annual tribute from the despots, which was only made more impossible by the fact that the local Greek nobility directly appealed to Mehmed II to be placed under his rule rather than that of the despots, making them untaxable. Meanwhile, the two brothers were on as poor of terms as ever. In 1458 CE, Mehmed had finally had enough, and invaded the Morea; after another devastating attack, Mehmed forced the despots to cede a third of their territory and submit yet again. In their final years of independence, Thomas and Demetrios continued to wage war against each other. In 1460 CE, Mehmed invaded, set this time on final conquest. Mystras fell without a fight. The city of Salmenikon was the last to hold out, until July 1461 CE. Demetrios bowed to Mehmed and entered his service. Meanwhile, Thomas fled to the west and would become a pensioner of the Pope. The Despotate of the Morea, the final appanage of the Byzantine Empire, was now part of the Ottoman Empire.