Thessaly was an independent state in medieval Greece from 1267 or 1268 to 1394 CE, first as the Greek-ruled Thessaly and later as the Catalan and Latin-ruled Duchy of Neopatras. Under its sebastokrators, Thessaly was a thorn in the side of the Byzantine Empire and an ally of the Latin states in Greece and southern Italy. Following the death of the last Thessalian sebastokrator in 1318 CE, the Duchy of Neopatras was established by the Catalans and combined with the Duchy of Athens, with the two states mostly sharing the same rulers and fortunes until Thessaly was finally conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1423 CE.

Beginnings in Epirus

Following the Fourth Crusade's sacking of Constantinople in 1204 CE, the Byzantine Empire splintered into a series of successor states. Thessaly was originally held by the regional Greek leader Leo Sgouros, but when the Latin crusaders arrived, the territory was quickly taken over by Latin lords under the nominal leadership of Boniface of Montferrat, the new King of Thessalonica (r. 1205-1207 CE). Latin rule in Thessaly was short-lived, however, and in 1212 CE, Michael I Komnenos Doukas of Epirus (r. 1205-1215 CE) occupied central Thessaly, including the key city of Larissa, and the rest of Thessaly was conquered by his half-brother and successor, Theodore Komnenos Doukas (r. 1215-1230 CE). Epirus was one of the three long-lasting Greek (or rather Roman) successor states to the Byzantine Empire, and it was initially quite successful, conquering Thessalonica, restyling itself the Empire of Thessalonica, and advancing almost to the gates of Constantinople itself before Theodore suffered a horrific defeat at the Battle of Klokotnitsa in 1230 CE.

In the aftermath of Klokotnitsa, Manuel Komnenos Doukas (r. 1230-1241 CE) took up power in Thessalonica while his relative Michael II Komnenos Doukas (r. 1230-1267/1268 CE) became the ruler of Epirus. Thessaly was ruled by the Empire of Thessalonica during this decade of contraction, but when Manuel was ousted from Thessalonica in 1237 CE by the returned Theodore, he went to Thessaly, where he ruled the region as an independent state from 1239 to 1241 CE. Upon his death, Thessaly fell to Michael II of Epirus, being reincorporated into the Despotate of Epirus. The region was briefly occupied by the Empire of Nicaea in 1259 but was reoccupied by Epirote forces the following year.

An Independent State

While Thessaly had a taste of independence under Manuel, in the will of Michael II, it would become an independent state once again. Michael II decided to split his realm between his firstborn son, Nikephoros Komnenos Doukas, and his illegitimate son John Doukas. Nikephoros (r. 1267/1268-1297 CE) received the Despotate of Epirus while John received Thessaly.

John I Doukas (r. 1267/1268-1289 CE) established the city of Neopatras as his capital and ruled Thessaly as a practically independent state. Like his half-brother Nikephoros, he technically was beholden to Byzantine suzerainty. John had received the imperial title sebastokrator from the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259-1282 CE), acknowledging Byzantine rule in the same manner that Nikephoros acknowledged Byzantine rule in Epirus in exchange for the title of despot. But in reality, both states operated outside of Byzantine rule and frequently allied themselves with their Latin neighbors to the south and in Italy.

John was on good relations with Charles I of Sicily (r. 1266-1285 CE), who coveted the Byzantine Empire, as well as the Duchy of Athens. Like Nikephoros, John also portrayed Thessaly as a protector of Orthodoxy when Michael VIII agreed to the union of the Orthodox and Catholic Churches at the Council of Lyon in 1274 CE. John even convened a synod at Neopatras to condemn the Council of Lyon and its proclaimed union.

In retaliation for John's disloyalty, a Byzantine army under Michael VIII's brother invaded Thessaly and besieged John in Neopatras. He was only saved by the timely arrival of an army from the Duchy of Athens. The price for this assistance, however, was the hand of John's daughter, Helena, in marriage to the future Athenian duke, William I de la Roche (r. 1280-1287 CE), as well as a dowry of a few Thessalian border towns. The Byzantines attempted to invade again in 1277 CE, and Michael VIII lead a campaign in person in 1282 CE but died en route.

While John I was a fearsome resistor of Byzantine rule, upon his death, he left two young sons as his successors, Constantine (r. 1289-1303 CE) and Theodore (r. 1289-1299 CE). John's widow, a Vlach princess, acquiesced to Byzantine power, and in 1295 CE, the Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos (r. 1282-1328 CE) granted both men the title of sebastokrator, like their father. The two sebastokrators were their father's sons, however, and soon were causing trouble for the Byzantines. They conspired with the Serbians and even attacked their cousin in Epirus, taking the city of Naupaktos.

End of the Dynasty

By 1303 CE, both Constantine and Theodore were dead, and another child was the ruler of Thessaly: Constantine's son John II Doukas (r. 1303-1318 CE). Due to his young age, Constantine had appointed the Duke of Athens, Guy II de la Roche (r. 1287-1308 CE), as John's guardian and the regent of Thessaly. Guy was John's uncle through marriage. He appointed a bailiff, Anthony le Flamenc, to rule Thessaly in his absence. Due to his family history and Guy's tutelage, John maintained Thessaly's strong connections with its Latin neighbors. Guy's guardianship forced an invading Epirote army to retreat, further strengthening Thessaly's relationships with the Latins.

However, to the north, a new crisis was brewing in the form of the Catalan Company. The Catalan Company was a group of mercenaries from the Kingdom of Aragon that was hired by the Byzantine emperor Andronikos II. After arriving in 1303 CE, they successfully defeated the Turks in several engagements, but their growing power terrified the Byzantines. In 1305 CE, the Catalan Company leader, Roger de Flor, was murdered, leading the Catalan Company to ravage Thrace for several years, utterly devastating the land. By 1309 CE, the Catalans having already sacked Byzantine territory to the fullest extent were looking for new opportunities. John II was now of age and was attempting to break free from Walter of Brienne, the new Duke of Athens (r. 1308-1311 CE). Walter called in the Catalan Company to assert Athenian power in Thessaly, and the mercenaries easily plundered the Thessalian plain and captured several Thessalian forts.

Much like the Byzantines before him, Walter was now alarmed at the ferociousness and bloody efficiency of the Catalan Company. He attempted to liquidate them, but the Catalans crushed the ducal army in 1311 CE at the Battle of Halmyros. Walter was killed in battle. In the aftermath, the Catalans conquered the Duchy of Athens itself. John struggled on for several more years, but the Catalans maintained the Thessalian forts they had conquered earlier and continued to raid deep into Thessaly. The Thessalian nobles also grew restless, and so John was forced to recognize Byzantine suzerainty. When John died in 1318 CE, the realm quickly dissolved, with the Catalans conquering the southern part of Thessaly and Greek nobles, Stephen Gabriolopoulos chief among them, ruling semi-autonomously in the north.

Duchy of Neopatras

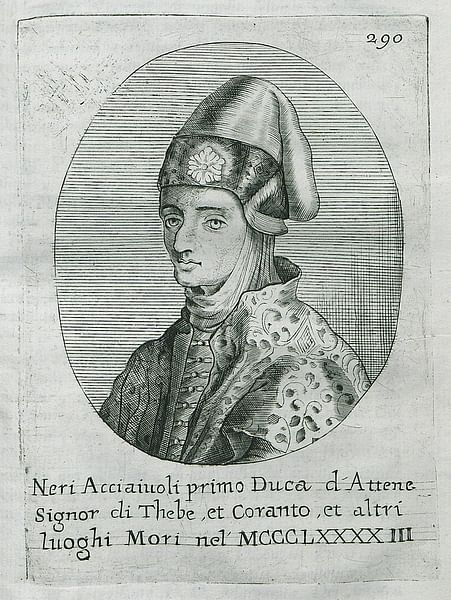

Although Thessaly was officially gone, it had a half-life of another century as the Duchy of Neopatras. The Catalans set up the Duchy of Neopatras in place of the southern half of Thessaly, but in reality, it was part of the Duchy of Athens. Catalan Athens was ruled by second and third sons of the Aragonese kings of Sicily, and thus the dukes of Neopatras and the dukes of Athens were one and the same. It was held by the Catalans until 1390 CE, when Nerio I Acciaioli (r. 1390-1391 CE), the Florentine lord of Corinth, conquered it, having wrested the Duchy of Athens from the Catalans two years before.

The Duchy of Neopatras under the Acciaioli would be short-lived. Four years later, in 1394 CE, the Ottomans conquered the duchy and advanced on Athens. After the Ottomans fell at the Battle of Ankara in 1402 CE against Timur (aka Tamerlane), the Byzantines reconquered Thessaly for a time, and the territory moved back and forth between the Byzantines and Ottomans until the Ottomans conquered it for good in 1423 CE. After its extended life of actual and nominal independence, Thessaly was now to be part of the Ottoman Empire for the next four centuries.