The Aztecs of ancient Mexico measured time with a sophisticated and interconnected triple calendar system which followed the movements of the celestial bodies and provided a comprehensive list of important religious festivals and sacred dates. Each day in the calendar was given a unique combination of a name and a number.

In addition, both individual days and periods of days were given their own gods in the calendar, highlighting the Aztec view that time and daily life was inseparable from religious beliefs. The date, every 52 years, when the calendars coincided exactly was regarded as particularly significant and auspicious.

The Aztec View of Time

In the modern world, time is often imagined as a straight line running from a distant past to an infinite future but not so for the Aztecs. As the historian R.F. Townsend describes,

Time for the Aztecs was full of energy and motion, the harbinger of change, and always charged with a potent sense of miraculous happening. The cosmogenic myths reveal a preoccupation with the process of creation, destruction and recreation, and the calendrical system reflected these notions about the character of time. (127)

For the Aztecs, specific times, dates and periods, such as one's birthday for example, could have an auspicious (or opposite) effect on one's personality, the success of harvests, the prosperity of a ruler's reign, and so on. Time was to be kept, measured, and recorded. It is significant that most major Aztec monuments and artworks conspicuously carry a date of some kind.

Tonalpohualli – 'Counting of the Days'

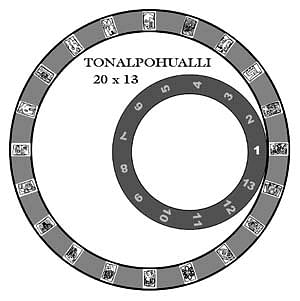

The Aztecs used a sacred calendar known as the tonalpohualli or 'counting of the days'. This went back to great antiquity in Mesoamerica, perhaps to the Olmec civilization of the 1st millennium BCE. It formed a 260-day cycle, in all probability originally based on astronomical observations. The calendar was broken down into units (sometimes referred to as trecenas) of 20 days with each day having its own name, symbol, patron deity and augury:

- cipactli - crocodile - Tonacatecuhtli - good

- ehecatl - wind - Quetzalcoatl - evil

- calli - house - Tepeyolohtli - good

- cuetzpallin - lizard - Huehuecoyotl - good

- coatl - snake - Chalchiutlicue - good

- miquiztli - death - Tecciztecatl / Meztli - evil

- mazatl - deer - Tlaloc - good

- tochtli - rabbit - Mayahuel - good

- atl - water - Xiuhtecuhtli - evil

- itzcuintli - dog - Mictlantecuhtli - good

- ozomatli - monkey - Xochipilli - neutral

- malinalli - dead grass - Patecatl - evil

- acatl - reed - Tezcatlipoca / Itztlacoliuhqui - evil

- ocelotl - ocelot / jaguar - Tlazolteotl - evil

- quauhtli - eagle - Xipe Totec - evil

- cozcaquauhtli - vulture - Itzpapalotl - good

- ollin - earthquake - Xolotl - neutral

- tecpatl - flint knife - Tezcatlipoca / Chalchiuhtotolin - good

- quiahuitl - rain - Tonatiuh / Chantico - evil

- xochitl - flower - Xochiquetzal - neutral

The 20-day group ran simultaneously with another group of 13 numbered days (perhaps not coincidentally the Aztec heaven had 13 layers). This meant that each day had both a name and a number (e.g.: 4-Rabbit), with the latter changing as the calendar rotated. After all possible combinations of names and numbers had been achieved, 260 days had passed. The number 260 has multiple significances: it is the approximate human gestation period, the period between the appearance of Venus, and the length of the Mesoamerican agricultural cycle.

In addition to names and numbers, each day was also given its own deity – one of thirteen day-lords (the levels of heaven) and one from nine night-lords (the levels of the underworld). These were taken from the Aztec pantheon and included Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, Tlaloc, Xiuhtecuhtli, and Mictlantecuhtli. Daylight hours also had their own patron birds such as the hummingbird, owl, turkey, and quetzal, and one day had a butterfly patron. On top of that, each group of 13 days was ascribed its own god too. Finally, in yet another layer of meaning, the 20 days were divided into four groups based on the cardinal points: acatl (east), tecpatl (north), calli (west), and tochtli (south).

This all seems rather complicated compared to a modern 7-day week of repeating names but it did have the advantage that every single day of the year had its own unique name and number combination and so could not be confused with any other. For this reason, it was possible for Aztec children to be given the name of the day on which they were born. Records were kept of the days in a book made of bark paper, called a tonalamatl. There was also a class of official diviners who interpreted which dates were the most auspicious for certain events such as marriages, and agricultural chores such as planting particular crops, and which days should be avoided.

Xiuhpohualli – 'Counting of the Years'

The second Aztec calendar was the xiuhpohualli or 'counting of the years' which was based on a 365-day solar cycle. It was this calendar which signified when particular religious ceremonies and festivals should be held. This calendar was divided into 18 groups of 20 days (each with its own festival). These 'months' were:

- Atlcahualo – stopping of the water

- Tlacaxipeualiztli – flaying of men

- Tozoztontli – lesser vigil

- Hueytozoztli – great vigil

- Toxcatl – drought

- Etzalqualiztli – eating maize and beans

- Tecuilhuitontli – lesser feast of the lords

- Hueytecuilhuitl – great feast of the lords

- Tlaxochimaco – offering of flowers

- Xocotlhuetzi – the fruit falls

- Ochpaniztli – sweeping

- Teotleco – return of the gods

- Tepeilhuitl – feast of the mountains

- Quecholli – a bird

- Panquetzaliztli – raising of the quetzal-feather banners

- Atemoztli – falling of water

- Tititl – unknown significance

- Izcalli - growth

Some scholars begin the sequence with Izcalli and so Atlcahualo becomes the second 'month' and so on. There was also an extra period, the nemontemi (literally, 'nameless' days) tagged onto the end of the year which lasted 5 days. These still did not ensure a complete solar accuracy (achieved by our leap-year) and so the calendar did eventually slip out of synch with the seasons, which necessitated the moving of festivals and even re-naming of days. The nemontemi was a strange period of limbo when nobody dared do anything significant but waited for the renewal of the calendar proper. The whole year had a name, one of four possibilities in sequence: Rabbit, Reed, Flint Knife, and House. To distinguish between repeating years they were each given one of 13 numbers, e.g. 1-House was followed by 2-Rabbit. Thus, when all four names had been used 13 times, one full 52-year cycle had passed.

The Calendars in Unison

The tonalpohualli and xiuhpohualli calendars ran simultaneously, as Townsend describes,

They have often been explained as two engaged, rotating gears, in which the beginning day of the larger 365-day wheel would align with the beginning day of the smaller 260-day cycle every 52 years. This 52-year period constituted a Mesoamerican “century”. (127)

The passing of one 52-year cycle (xiuhmolpilli) to another was marked by the most important religious event of the Aztec world, the New Fire Ceremony, also known, appropriately enough, as the 'Binding of the Years' ceremony. This was when a human sacrifice was made to ensure the renewal of the sun. If the gods were displeased, then there would be no new sun and the world would end.

Every second 52-year cycle was even more important to the Aztecs as this was when the tonalpohualli and the 52-year cycle coincided exactly. Curiously, although the 52-year periods were important blocks in Aztec history, they were never given an individual name and all dates started afresh at the beginning of a new cycle. This, no doubt, reflected the Aztec cosmos mythology where the world and humanity were being constantly renewed in perpetual cycles of change.