To this day the ancient Romans remain infamous for their dramatic use of spectacle and other forms of entertainment. A lesser known variation of Roman spectacle is the mythological re-enactments that took place during the ludi meridiani (midday spectacle). These performances were not only re-enactments for entertainment's sake, but were also a very real form of execution. The unfortunate souls forced to re-enact the myths were primarily condemned criminals who had committed a capital offense, but they may also have been prisoners of war. Within the Roman world it was only the humiliores (people of lower status) and non-citizens who were condemned to die in such a way, as public executions were often performed in a manner that was considered degrading and humiliating. Kathleen M. Coleman suggests that non-citizens, along with lowly criminals, were entitled to the most degrading of penalties as a result of their lack of status within society. It was the intent of the individual responsible for condemning the criminals/prisoners to separate the condemned from society, both physically and emotionally, in order to prevent sympathy among the spectators. By humiliating the condemned, the spectators would experience a sort of shared moral superiority over the individual that had been sentenced to die.

Although it is difficult to determine the true motives behind the executions, it is probable that the emperor would hold such games as the ludi meridiani in order to control the population and allow the re-enactments to serve as an example of what may happen to the public if they, too, broke the law. Whether or not this was the case, and whether or not this was effective, remains unclear. It is clear, however, that such spectacles served a political purpose, and the inclusion of myth is no coincidence. As ancient Greek and Roman history was measured in terms of myths, myths were, in turn, incorporated into many aspects of daily life and spectacle within the ancient world, serving political, social, and religious purposes alike.

Primary sources of such events include Martial, a 1st century CE poet, and Clement of Alexandria, a 2nd-3rd century Christian theologian. Martial's work On the Spectacles describes the inaugural games of Titus in 80 CE and provides three accounts of mythological re-enactments. These include: Hercules, Orpheus, and Pasiphae.

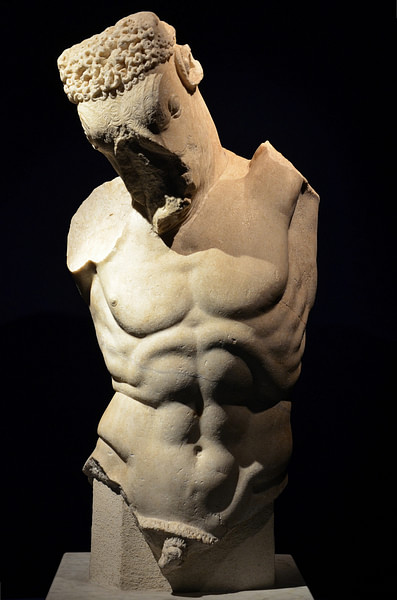

HERCULES

It is likely that the Romans specifically chose the most popular myths and characters in order for the condemned to be readily identified, such as Hercules clad in a lion's skin clutching a club. The inevitable outcome of this re-enactment was crematio (cremation) as within the myth. The setting itself may differ from the myth, yet it is believed that the most common setting for the re-enactment of the Hercules myth would take place on the immolation pyre of Mount Ida. If not, then the re-enactment would simply include "Hercules" wearing the garment given to him by Deianira, which according to myth had been smeared with the centaur Nessus' blood. In reality, the tunic was doused in pitch in order to become more flammable. This tunic was given the name tunica molesta. In comparison to the original myth itself, this re-enactment is quite similar. The attributes of Hercules are generally the same, even the tunic given to him by Deianira. Most importantly, the outcome of the myth is still the same as well; "Hercules" dies by being burned alive one way or another.

ORPHEUS

In regards to Orpheus, another easily identifiable figure in mythology, Martial describes a manipulation of the myth. Although Orpheus would have remained identifiable by carrying a lyre, perhaps even playing music and singing, the outcome of the myth was altered. Unlike the myth, Martial records that the death of "Orpheus" was caused by a bear rather than the Bacchae. In this re-enactment, the wonders of the amphitheatre would have been put into effect, taking advantage of the multiple entrances, trap doors, and scenic displays. "Orpheus" would have entered the area with his lyre, while tame and harmless animals would have been slowly released. Some of these animals may have even been trained to interact with the character and his music. Finally, a bear would have been released, and perhaps "Orpheus" would have even been netted to prevent escape. Once "Orpheus" was trapped and the bear released, the criminal would have been torn apart, likely interpreted as an ironic twist to the myth, which the audience, not having anticipated this, would find entertaining and full of suspense: "Orpheus," killed by the very beast he was meant to charm.

PASIPHAE

Finally, Martial also recounts the re-enactment of Pasiphae, the wife of King Minos, and mother of the Minotaur. According to myth, it was King Minos who brought doom upon Pasiphae, cheating Poseidon of a magnificent bull that was meant to be sacrificed to him in return for legitimizing King Minos' claim for the throne. In punishment for this crime, Pasiphae was cursed to fall in love with the bull. Full of desire for the animal, she requested the craftsman Daedalus to construct for her a wooden cow covered in a hide so she could climb inside and join with the bull in his field. Ovid makes fun of the situation within his work, Ars Amatoria, stating, "Pasiphae shouted for joy when the animal made her his mistress...Well, the lord of the harem, deceived by a wooden plush-covered dummy, got Pasiphae pregnant. The child looked just like his dad". (289)

DIRCE & THE DANAIDS

Two more ambiguous myths that are recorded to have been re-enacted are those of Dirce and the Danaids. In describing the persecution of Christians, Clement of Alexandria records that, "Women suffered persecutions as Danaids and Dirce because of their commitment. After they had experienced acute and unspeakable torture, they trod the firm track of their faith and, physically frail, received their noble reward."[4] It appears that the myths of Dirce and the Danaids may have been reserved for Christian women, although whether or not there was a level of significance behind this is unclear.

Within the myth, Dirce is tied to the horns of a wild bull and dragged to her death by Zethus and Amphion, sons of Antiope, who were held prisoner by Dirce. In this case, the myth and re-enactment were essentially the same. Within the arena, a condemned woman, often a Christian, was forced to re-enact this myth and tied to the horns of a bull and dragged to her death. In the case of the Danaids, however, the relationship between myth and re-enactment is less clear.

According to mythology, the story of the Danaids differs from source to source. The 50 daughters of Danaüs were married to the 50 sons of his brother, Aegyptus, but only after much persuasion. Danaüs gave each of his daughters a dagger and instructions to kill their husbands on the night of their wedding; all but one daughter does so. Their punishment seems to vary, yet in the Hellenistic period it appears the common belief was the Danaids were forced to carry water to the underworld or Hades with leaky vessels to fill a trough, or perhaps forced to fill a bottomless vessel. Within the area their punishment is even more unclear, as the "Danaids" were only recognized by their vessels, which they were forced to carry. The means of their death is unknown and were likely created for the re-enactment alone.

ATTIS

Coleman describes an additional mythological re-enactment concerning Attis. According to Ovid, Attis was a gorgeous Phrygian youth that was loved by the mother of the gods, Cybele. Attis consecrated himself to her by swearing eternal faithfulness, betraying her with a tree-nymph named Sagaritis, and who was then driven mad resulting in his self-inflicted emasculation. Within Catullus' song 63, Attis is described as a youth that emasculated himself as the result of the insanity Cybele infused on him, while an alternate version of the myth refers to the youth as the Galli, the head eunuch priest of Cybele. The end result was the same within the re-enactments. The criminal condemned to die as "Attis" would inevitably be castrated which was perhaps even self-inflicted. Coining the term "fatal charades," Coleman addresses this myth within her investigation of the re-enactments. In her opinion the castration in itself was not considered to be fatal. Instead, the re-enactment of Attis may have been used as a means of torture during cross-examination instead. In order for "Attis" to actually castrate himself it is likely that the individual would have been threatened with death if he refused to do so. Chances are the condemned was aware that they would die either way, as the re-enactments were a form of execution as a whole, and it is difficult to believe that threatening the condemned really worked. What is most probable is that "Attis" would have been impaled instead, and instructed to castrate himself if he was to be free. Certainly a graphic concept, but it would likely have worked.

SOCIAL & POLITICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF MYTH IN THE ARENA

Much like the works of Martial, the mythological re-enactments held political significance and both can be attributed to commission by the emperor. In fact, by recreating myth the emperor gained control over it. He was not only able to draw in the crowds using spectacle as a means of propaganda, but he was also able to show the public that as emperor he had power over history and the myths themselves. To go even further, whenever the myth of Orpheus was re-enacted and the condemned was killed by a bear rather than the Bacchae, the audience would have been pleased with the innovative change while also noting that the emperor was not only able to recreate myth, but alter it as well. An emperor that was able to recreate myth was able to "prove" that a myth was real and therefore able to work a miracle.

In a world where myth and history are bound to one another, the individual that can lay claim to mythology not only holds power over history, but also holds the ability to lay claim to whatever prestige and power the myths themselves possess. Indeed, members of the aristocracy would have easily recognized the concept of associating oneself with myth and appropriating the powers connected with it, for the elite had followed this practice for generations. The Romans believed that through myth, morality, conduct and virtues of the nobility were learned. Naturally, many would attempt to claim mythological lineage in order to deserve such noble traits. Cities and regions also connected their heritage to mythological heroes as they often displayed important elements of valorization, among which include great age, civilizing deeds, and martial bravery.

The Romans placed a great amount of respect on religions and cultures that were able to boast antiquity, and the same theory was applied to individuals as well. Although fictitious beyond the third or fourth generation, the elite were often found to associate one's family with ancient or mythological heroes and kings in order to boast a claim to the same prestige that the alleged ancestor had once possessed. This is not so different from the holders of the games themselves, those who organized the most effective and grand spectacles in order to honour and gain prestige for their own family. As myth held an integral place within Roman ancestry, society, politics and religion, there can be no surprise that the mythological re-enactments within Roman spectacle held an important role as well. Although few modern and ancient sources address the practice directly, mythological re-enactments serve a subtle, yet valuable role within the Roman games as a means of propaganda and control that should not be overlooked.