In 1848, Ellen and William Craft escaped from slavery in Georgia by Ellen posing as a Southern gentleman and William as 'his' slave (since women were not allowed to travel alone with a male slave). They arrived in the free state of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia, on Christmas Day 1848, were taken in by the Vigilance Committee, and sent on to Boston. There, they were understood to be free people, safe from capture and re-enslavement, until the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

In October 1850, two slave=catchers arrived in Boston from Georgia to bring the Crafts back to their former master. The incident was recorded by the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879) in his anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, in November 1850, and his article was saved and reprinted by the abolitionist William Still (1819-1902) in his work, The Underground Railroad Records (1872), along with Still's narrative of Boston's reception of the slave-catchers and the Crafts' later flight to Great Britain, given below.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was passed by the US Congress on 4 February 1793 to provide the legal means of enforcing the Fugitive Slave Clause of the United States Constitution (Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3), giving slaveowners the right to retrieve their fugitive slaves from wherever they might have gone.

No escaped slave, therefore, could be confident in their freedom because, at any time, once they were located, they could legally be reenslaved. No one, however, was legally compelled to inform on the fugitive. It was up to the slaveholder to locate and then organize the capture of their former slave.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 strengthened the Act of 1793 by mandating that citizens of free states, law enforcement and judicial officials, and public servants aid slave-catchers in finding and capturing fugitives (today referred to as 'freedom seekers). Further, those who refused to do so or helped freedom seekers evade capture in any way faced fines and imprisonment.

Anyone convicted of helping a freedom seeker was subject to a fine of $1,000.00 (equal to around $37,000.00 today) and six months in prison. Once a freedom seeker was caught, they were brought before a commissioner, who ruled on whether the person was a fugitive slave or a free Black. Commissioners were paid a stipend for performing this duty, but it was weighted heavily in favor of declaring the person a slave. A decision sending the person back to slavery was rewarded with $10.00 (equal to around $380.00 today), while a verdict freeing the person netted the commissioner only $5.00 (around $190.00 today). Commissioners, therefore, tended to decide in favor of the slave-catchers.

It was not only freedom seekers who might be caught and enslaved, however, but any free Black that a slave-catcher managed to ensnare. The slave-catcher would then make up a name and backstory for the 'slave' and sell him or her to a slave trader. This policy was followed even before the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

The most famous example of this is the case of Solomon Northup (circa 1807/1808 to circa 1857/1864), a free Black man from Saratoga Springs, New York, who was drugged and sold into slavery in New Orleans, Louisiana, under the name Platt Hamilton in 1841. His family had no idea where he had gone or how to locate him. He only regained his freedom twelve years later when a sympathetic Quaker, Samuel Bass (1807-1853), alerted Northup's family to his whereabouts, and they were able to have him freed and brought home. Northup then detailed his experience in his book, Twelve Years a Slave (1853), which became a bestseller at the time and a major motion picture in 2013.

After 1850, this same practice that had enslaved Northup continued, but on a larger scale. In his case, the two men who tricked and sold him were acting out of self-interest, but, after 1850, informing on the whereabouts of a fugitive slave – or a free Black one could claim as such – was the law and 'catching' any Black person, free or fugitive, netted the informer or catcher a significant sum of money. Free Black children, especially, were in danger of being kidnapped and sold into slavery at any slave auction in any slave state in the South.

Resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act

Prior to the Fugitive Slave Act, what happened to freedom seekers once they had fled to the North seems to have been of little concern to most White people in the free states. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in September 1850, however, people were forced to engage with the 'peculiar institution' of slavery even if they did not want to. One had to decide whether to help a freedom seeker or turn the person in for a reward. The Fugitive Slave Act had the unforeseen result of galvanizing people in the North, especially the abolitionists, in resisting the act, helping slaves to freedom in Canada, and working within the law to imprison, fine, and expel slave-catchers.

As the text below illustrates, the people of Boston were no friends to the slave-catchers, and the lawyers of the city were quick to find any excuse to have them jailed and fined. The free Black community of Boston, naturally, resisted the act, hid fugitives, and helped send them on to Canada via the Underground Railroad. Harriet Tubman (circa 1822-1913) led some of these freedom seekers to Canada herself.

In the case of Ellen Craft (1826-1891) and William Craft (1824-1900), prior to 1850, they would still have been at risk of slave-catchers from the South coming to retrieve them in Boston, but they would not have had to worry about someone – anyone – they encountered informing on them, as the law now mandated should be done.

The Boston community rallied around the Crafts, protected them from the slave-catchers, and, realizing they would never be safe from re-enslavement in the United States, sent them to Great Britain, where they lived for the next 19 years, co-authoring their book, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom (1860), describing their escape from slavery.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was severely weakened by the outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-1865) but remained on the books until it was formally repealed in June 1864. In 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, and in 1868, the Crafts were able to return to the United States, with their children, as free people.

Text

The following is taken from The Underground Railroad Records by William Still, republished by Modern Library, New York, 2019. "Slave Hunters in Boston" was an article in The Liberator by William Lloyd Garrison, 1 November 1850, reprinted by Still in his discussion of the escape and attempted re-enslavement of Ellen and William Craft.

In the excerpt below, Garrison's piece ends just before Still resumes his narrative of the Crafts with the story of Mrs. Hilliard and her efforts in helping the Crafts.

From "The Liberator", Nov. 1, 1850: SLAVE HUNTERS IN BOSTON:

Our city, for a week past, has been thrown into a state of intense excitement by the appearance of two prowling villains, named Hughes and Knight, from Macon, Georgia, for the purpose of seizing William and Ellen Craft, under the infernal Fugitive Slave Bill, and carrying them back to the hell of slavery.

Since the day of '76, there has not been such a popular demonstration on the side of human freedom in this region. The humane and patriotic contagion has infected all classes. Scarcely any other subject has been talked about in the streets, or in the social circle.

On Thursday, of last week, warrants for the arrest of William and Ellen were issued by Judge Levi Woodbury, but no officer has yet been found ready or bold enough to serve them. In the meantime, the Vigilance Committee, appointed at the Faneuil Hall meeting, has not been idle. Their number has been increased to upwards of a hundred "good men and true," including some thirty or forty members of the bar; and they have been in constant session, devising every legal method to baffle the pursuing bloodhounds, and relieve the city of their hateful presence.

On Saturday, placards were posted up in all directions, announcing the arrival of these slave-hunters, and describing their persons. On the same day, Hughes and Knight were arrested on the charge of slander against William Craft. The Chronotype says, the damages laid at $10,000.00; bail was demanded in the same sum and was promptly furnished. By whom? is the question.

An immense crowd was assembled in front of the Sheriff's office, while the bail matter was being arranged. The reporters were not admitted. It was only known that Watson Freeman, Esq., who once declared his readiness to hang any number of negroes remarkably cheap, came in, saying that the arrest was a shame, all a humbug, the trick of the damned abolitionists, and proclaimed his readiness to stand bail.

John H. Pearson was also sent for, and came – the same John H. Pearson, merchant and Southern packet agent, who immortalized himself by sending back, on the 10th of September, 1846, in the bark Niagara, a poor fugitive slave, who came secreted in the brig Ottoman, from New Orleans – being himself judge, jury, and executioner, to consign a fellow-being to a life of bondage – in obedience to the law of a slave State, and in violation of the law of his own.

This same John H. Pearson, not contented with his previous infamy, was on hand. There is a story that the slave-hunters have been his table-guests also and whether he bailed them or not, we don't know. What we know is, that soon after Pearson came out from the back room, here he and Knight and the sheriff had been closeted, the Sheriff said that Knight was bailed – he would not say by whom.

Knight, being looked after, was not to be found. He had slipped out through a back door, and thus cheated the crowd of the pleasure of greeting him…Hughes and Knight have since been twice arrested and put under bonds of $10,000.00 (making $30,000.00 in all), charged with a conspiracy to kidnap and abduct William Craft, a peaceable citizen of Massachusetts, etc. Bail was entered by Hamilton Willis, of Willis & Co., 25 State Street, and Patrick Riley, US Deputy Marshal.

At a meeting of colored people, held in the Belknap Street Church, on Friday evening, the following resolutions were unanimously adopted:

Resolved: That God willed us free; man willed us slaves. We will as God wills; God's will be done.

Resolved: That our oft-repeated determination to resist oppression is the same now as ever, and we pledge ourselves, at all hazards, to resist unto death any attempt upon our liberties.

Resolved: That, as South Carolina seizes and imprisons colored seamen from the North, under the plea that it is to prevent insurrection and rebellion among her colored population, the authorities of the State, and city in particular, be requested to lay hold of, and put in prison, immediately, any and all fugitive slave hunters who may be found among us, upon the same ground, and for similar reasons.

Spirited addresses, of a most emphatic type, were made by Messrs. Remond, of Salem, Roberts, Nell, and Allen, of Boston, and Davis, of Plymouth. Individuals and highly respectable committees of gentlemen have repeatedly waited upon these Georgia miscreants, to persuade them to make a speedy departure from the city. After promising to do so, and repeatedly falsifying their word, it is said that they left on Wednesday afternoon, in the express train for New York, and thus (says the Chronotype), they have "gone off with their ears full of fleas, to fire the solemn word for the dissolution of the Union!"

Telegraphic intelligence is received that President Fillmore has announced his determination to sustain the Fugitive Slave Bill, at all hazards. Let him try! The fugitives, as well as the colored people generally, seem determined to carry out the spirit of the resolutions to their fullest extent.

Ellen first received information that the slave-hunters from Georgia were after her through Mrs. Geo. S. Hilliard, of Boston, who had been a good friend to her from the day of her arrival from slavery. How Mrs. Hilliard obtained the information, the impression it made on Ellen, and where she was secreted, the following extract of a letter written by Mrs. Hilliard, touching the memorable event, will be found most interesting.

"In regard to William and Ellen Craft, it is true that we received her at our house when the first warrant under the act of eighteen hundred and fifty was issued.

Dr. Bowditch called upon us to say that the warrant must be for William and Ellen, as they were the only fugitives here known to have come from Georgia, and the Dr. asked what we could do. I went to the house of the Rev. E.T. Gray, on Mt. Vernon Street, where Ellen was working with Miss Dean, an upholsteress, a friend of ours, who had told us she would teach Ellen her trade. I proposed to Ellen to come and do some work for me, intending not to alarm her. My manner, which I supposed to be indifferent and calm, betrayed me, and she threw herself into my arms, sobbing and weeping. She, however, recovered her composure as soon as we reached the street, and was very firm ever after.

My husband wished her, by all means, to be brought to our house, and to remain under his protection, saying, 'I am perfectly willing to meet the penalty, should she be found here, but will never give her up.' The penalty, you remember, was six months' imprisonment and a thousand dollars fine. William Craft went, after a time, to Lewis Haden.

He was at first, as Dr. Bowditch told us, 'barricaded in his shop on Cambridge Street.' I saw him there, and he said, 'Ellen must not be left at your house.' 'Why, Willian,' said I, 'do you think we would give her up?' 'Never,' said he, 'but Mr. Hilliard is not only our friend, but he is a U.S. Commissioner, and should Ellen be found in his house, he must resign his office, as well as incur the penalty of the law, and I will not subject a friend to such a punishment for the sake of our safety.'

Was not this noble, when you think how small was the penalty that anyone could receive for aiding slaves to escape, compared to the fate which threatened them in case they were captured? William C. made the same objection to having his wife taken to Mr. Ellis Gray Loring's, he also being a friend and a commissioner."

This deed of humanity and Christian charity is worthy to be commemorated and classed with the act of the Good Samaritan, as the same spirit is shown in both cases. Often was Mrs. Hilliard's house an asylum for fugitive slaves.

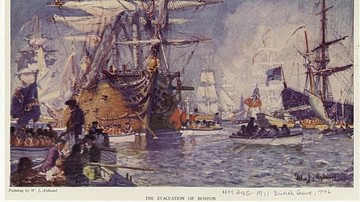

After the hunters had left the city in dismay, and the storm of excitement had partially subsided, the friends of William and Ellen concluded that they had better seek a country where they would not be in daily fear of slavecatchers, backed by the Government of the United States.

They were, therefore, advised to go to Great Britain. Outfits were liberally provided for them, passages procured, and they took their departure for a habitation in a foreign land.