The First Battle of El Alamein (1-27 July 1942) was a series of encounters during the Second World War (1939-1945) in Egypt between Allied and Axis forces. The battle, focussed around the El Alamein defensive line, ended without a decisive result except that the advance into Egypt of the German General Erwin Rommel (1891-1944) was finally halted.

The British Eighth Army followed up with a victory at the Battle of Alam Halfa (September 1942) and then definitively turned the tide of the war in North Africa by winning the great set-piece encounter known as the Second Battle of El Alamein in October-November 1942.

The Importance of North Africa

North Africa became a major theatre of WWII because of the importance of holding the Suez Canal and protecting vital shipping routes in the Mediterranean. In the early years of the war, North Africa was the only place where Britain could fight a land war against the Axis powers of Germany and Italy and so hopefully gain much-needed victories that would encourage the British people after the debacle of the Dunkirk Evacuation and the horrors of the London Blitz. The fighting in North Africa, which involved infantry, artillery, armoured divisions, and air support, became known as the Western Desert Campaigns (June 1940 to January 1943).

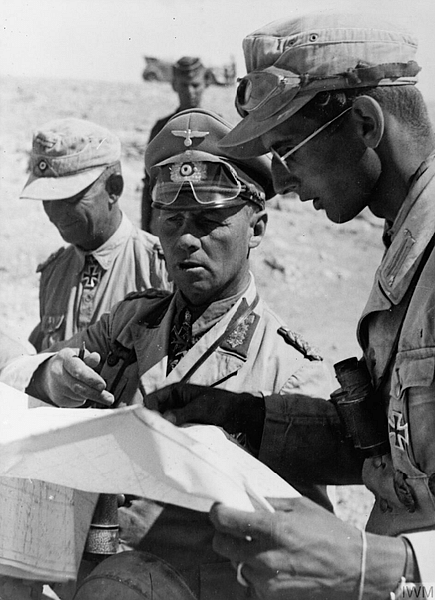

With Operation Compass (December 1940 to February 1941), British and British Empire troops obliged Italy's poorly equipped army to withdraw from Egypt and then Cyrenaica (Eastern Libya). From February, the Axis presence in North Africa was considerably boosted by the arrival of German troops such as the elite Deutsche Afrika Korps (DAK) with superior armour, weapons, and training compared to both the Italians and the Allies. Things improved further for the Axis powers when General Rommel took over command of Axis forces in North Africa. Rommel won a series of victories in March and April 1941, but the Allies kept hold of their vital supply port during the siege of Tobruk (April to December 1941). Rommel regained the initiative at the Battle of Gazala (May-June 1942) where the Allied Gazala Line of defences was smashed. Rommel even captured Tobruk on 21 June and so was promoted to the rank of field marshal. Rommel gained another victory at the Battle of Mersa Matruh, capturing the Egyptian port on 28 June. Here, as in other arenas of the conflict, the Allies were taking a beating.

Rommel Eyes Egypt

The Allies were obliged to conduct a fighting retreat and regroup behind a new defensive line, this time at El Alamein in Egypt. With backing from both Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), Rommel was determined to pursue and smash the enemy rather than allow the Allies to regroup and come back stronger. The Suez Canal and port of Alexandria were in imminent danger of capture by Axis forces, but they would have to act quickly, before Allied troops in North Africa received reinforcements from the Middle East and, most importantly of all, before United States troops arrived in this arena.

The Allies were severely hampered by having a lethal combination of poorly trained troops, poor equipment, poor multi-arms cooperation, and poor commanders who could not cope with Rommel's tactics of using his armour with speed and audacity. Rommel's tactics more than compensated for his numerical inferiority in men and tanks compared to the Allies.

The Allied fighting force in Africa was the British Eighth Army, and it had lost 50,000 men to Rommel's latest round of successes, but thanks to reserves coming from Egypt and Syria, it remained a formidable obstacle to Rommel's ambitions. The Eighth Army's new commander was General Claude Auchinleck (1884-1981), who was also commander-in-chief of Allied troops in the Middle East, but he decided to take personal command in North Africa. As Auchinleck put it, "The danger of complete catastrophe was too great for me to leave the responsibility with a subordinate" (Mitchelhill-Green, 348).

The El Alamein Defences

El Alamein was a tiny desert railway halt built in the 1920s and located 60 miles (95 km) west of Alexandria. Stretching from the coast to 40 miles (65 km) inland, the El Alamein Line was a much better line to defend than at Gazala since the southern end could not be outflanked by the enemy thanks to the Qattara Depression, a vast area of soft sands and salt marshes that could not be crossed by heavy vehicles. As the historian D. Allen Butler puts it, "If Rommel was going to take Cairo, he would have to go through Eighth Army, not around it" (343). Another advantage of the El Alamein Line over the featureless Gazala Line was the Ruweisat Ridge in the middle of it, a low rocky outcrop some 8 miles (13 km) long, which provided excellent natural cover for both tanks and artillery. Further beneficial features for the defenders were the steep escarpment that bordered the Qattara Depression and the Deir el Munnsaib Depression, both of which obliged a commander to send his troops into particular places which could be prepared beforehand. It is no surprise then that British commanders had identified El Alamein as a potential area of defence back in the 1930s.

Auchinleck now used every available hour to strengthen his defences as gunners and tanks dug in, yet more mines were laid, and the infantry frantically filled sandbags to better protect their positions. Knowing he did not have sufficient troops to defend the entire stretch of the line, Auchinleck created three major 'boxes', one at the northern end of the line (El Alamein), one to the south (Naqb Abu Dweiss), and one in the centre (Bab el Qattara). Realising these boxes were too far apart, a fourth, called Deir el Shein, was laid out between Alamein and Bab el Qattara.

The 'boxes' were defended in strength but depended on mobile units for support and to cover the gaps between them. Each 'box' contained two infantry battalions and three batteries of artillery – one each of field, anti-aircraft, and anti-tank guns. In addition, in case everything went wrong and once again a retreat was required, another line of defences was prepared to the rear. There was much activity in Alexandria and Cairo, too, where government officials were desperately gathering up their papers, burning secret files, and generally getting ready for a full evacuation. Despite the fears of another setback, Auchinleck, at least to his men, presented a determination to stand and fight at El Alamein. The commander sent the following message to all ranks of the Eighth Army:

The enemy is stretched to the limit and thinks we are a broken army…He [Rommel] hopes to take Egypt by bluff. Show him where he gets off.

(Holland, 193)

Weapons

As in previous battles, the British Army included all manner of empire troops, including Australians, Indians, Nepalese, New Zealanders, and South Africans. The best of the British troops was the battle-hardened 7th Armoured Division, known as the 'Desert Rats' for their badge emblem, a jerboa. The Allies received some important equipment upgrades in the summer of 1942. The newly arrived US-made Lee and Grant tanks finally gave some equality with the German Panzer IV tanks. Both US tanks had a 75mm and a 37mm gun. Another valuable addition to Allied armoury was the 6-pounder (57 mm) anti-tank gun, capable of firing a 2.84-kg shell through armour 50 mm (2 in) thick. The Axis powers' most destructive weapon remained the 88mm artillery gun, which was originally designed as an anti-aircraft gun but used by the DAK as a horizontal anti-tank weapon with devastating effect against all enemy armour.

One weapon the Allies had which the Axis powers did not was the use of special forces. The Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) and the Special Air Service Brigade (SAS), now equipped with customised US jeeps, carried out daring raids behind enemy lines, destroying vital equipment and supplies, particularly enemy aircraft and airfields. Another important role of the LRDG was to spot enemy supply convoys and alert the Allied air force so that they could be attacked and destroyed.

A final weapon was military intelligence. Auchinleck was assisted by interceptions and decodings of Axis communications by the Allied ULTRA unit which allowed him to some degree to know what Rommel planned, although because the field marshal rarely communicated his plans to his superiors, this was not always as helpful as it might have been. Rommel had his own intelligence from a unit intercepting Allied communications between Europe and America, but this source was discovered. A second source of intelligence was a specialised DAK unit, Kompanie 621, which listened in to radio chatter between Allied soldiers, not a source of high-level decision-making but often useful when troops were given orders to take up new positions. Unfortunately for Rommel, Kompanie 621 was put out of action when it was attacked and captured in mid-July.

Rommel Attacks

Rommel's army had been greatly replenished in ammunition, transport, and fuel when it had captured Tobruk, but its permanent supply lines remained dangerously stretched. In addition, the mad chase after the retreating Allies across the border into Egypt had taken its toll on the Axis troops and tanks. Rommel had only around 85 tanks left, and 30 of these were inferior Italian types. The German general still had 300 guns, including 29 of the 88mm tank-busters. Both sides badly needed to rest and make good their losses in men and material. What followed was a series of disparate actions collectively called the First Battle of El Alamein, although some modern historians prefer not to classify these engagements as a single battle.

Rommel attacked the Allied positions at El Alamein on 1 July and again on 3 July, concentrating on the northern and central 'boxes'. Both times Rommel was repulsed. Rommel had underestimated perhaps the capacity of resistance of those parts of the line he attacked and the strength of the enemy's air force. The Allied Western Desert Air Force flew over 2,000 sorties between 2 and 5 July. In addition, the unexpected presence of an entire Indian division wrecked Rommel's plan of attack and a sudden sandstorm seriously delayed the deployment of his tanks. Rommel lost about one-quarter of his tanks in these first few days of the battle. Dysentery was also wreaking havoc with the Axis army. Refusing to withdraw, Rommel turned to digging his own defensive lines while a series of minor skirmishes followed over the next few days. On 9 July, Rommel attacked the southern Allied 'box'.

Auchinleck Counterattacks

On 10 July, at the Battle of Tell el Eisa (10 July), General William Ramsden sent two divisions (9th Australian and 1st South African) against Rommel's Italian troops at the northern end of the line. The engagement was again indecisive, although the Italian losses were significant. A pattern was being established where neither side could make any real territorial progress against the other. On 14 July, General William Gott deployed another two divisions (New Zealand and 5th Indian) in an engagement which became known as the First Battle of Ruweisat. The Allied troops faced two Italian divisions, but after two days and with support coming from Rommel's German troops, the engagement finished, yet again, with nobody making any significant gain. Auchinleck's belief that the Italians were the weak link of the Axis army turned out to be wrong. The battle was becoming a stalemate as "Eighth Army's advantages in numbers could not counter its enemy's superior tactics" (Butler, 353). Both sides were also by now seriously limited by a lack of ammunition.

The battle of attrition was part of the Allied plan, summarised as follows by General John Strawson:

To concentrate the army, to fight it in integrated battle groups, to mass the artillery, to husband the armour, to form a light armoured brigade for flank reconnaissance, to attack and wear down the Italian divisions.

(Strawson, 141)

Auchinleck, determined not to allow Rommel time to make repairs and reorganise, launched another attack on 21 July in the Second Battle of Ruweisat. The night attack made some gains at first, but Rommel counterattacked to re-establish the status quo. The Allies, despite enjoying a numerical advantage in armour and men, were once more paying the price for a lack of coordination between the armour and infantry when attacking (although in defensive mode this cooperation had greatly improved). The British lost 121 tanks on 22 July alone compared to Rommel's loss of just three tanks. Another Allied push on 23 and 26 July proved ineffective. The veteran Axis troops were proving remarkably able to resist anything thrown at them.

Assessment

Rommel's advance was certainly halted by these minor battles, although whether this was because of Allied endeavour or his lack of supplies is still a matter of debate amongst historians. It is generally felt that Rommel's force was not ready for a major battle and that the static warfare around El Alamein was much more to the advantage of the Allies with their material superiority, command of the best terrain, and greater capacity to replace men and supplies. No longer able to dictate the terms on which battles were fought, Rommel's abilities at ambitious high-speed warfare had become much less relevant to the outcome of the encounters.

Rommel had outdistanced both his logistical capabilities and possible air support. The general himself noted that the gamble on a quick victory had failed, and he had "brought the strength of my Army to the point of exhaustion" (Clark, 210-11). Even worse in the longer term, the lack of success for Germany on the Russian Front diminished Rommel's chances of ever gaining sufficient resources to conduct his campaign how he wished. In addition, the Axis air and naval presence in the Mediterranean was weakening, and so even the few supplies directed to North Africa were not guaranteed to arrive there. As Allen Butler notes, "for the first eight months of 1942, only 40 percent of the total tonnage needed to sustain his [Rommel's] divisions actually reached Panzerarmee Afrika [as it was now called]" (362).

The fact remained, though, that Rommel was in the field and still a threat to Egypt. The First Battle of El Alamein had not achieved the Eighth Army's objectives. As the military historian Niall Barr summarises:

No important ground had been wrested from the Panzerarmee Afrika, and much of the Eighth Army's strength had been wasted in hasty attacks that broke down in confusion…Eighth Army had suffered more than 13,000 casualties…Axis casualties are very difficult to estimate but at least 7,000 German and Italian troops had been captured... Neither army had achieved its goal.

(184)

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965), disappointed that Rommel had not been decisively defeated, had Auchinleck replaced by General Harold Alexander (1891-1969) as commander-in-chief in the Middle East. With public opinion and that of his major ally the United States in mind, the pressure was mounting on Churchill to deliver a decisive victory in North Africa, which could then act as a platform for an Allied invasion of southern Europe.

Aftermath

El Alamein was a stalemate, but it was the beginning of a definitive turning point in the Western Desert Campaigns. The Allies, gaining in strength as more and more resources arrived at Alexandria, next won the Battle of Alam Halfa (August-September 1942). The British army benefitted from a large influx of superior US tanks and artillery pieces and greatly improved air support provided by a much-enlarged Western Desert Air Force. In contrast, Rommel's air support dwindled the further east he moved, and his logistics lines were at breaking point. Perhaps just as significantly, the British Eighth Army's new commander from August 1942 was General Bernard Montgomery (1887-1976), and he revitalised his troops. Montgomery much more effectively combined artillery, infantry, and armoured divisions to inflict a heavy defeat on Rommel in October-November at the Second Battle of El Alamein, but despite mopping up 30,000 prisoners, Rommel was permitted to withdraw to fight another day. Tobruk was then retaken by the Allies.

In Operation Torch of November 1942, three new Allied armies, which included the Western Task Force commanded by General George Patton (1885-1945), landed in North Africa in November 1942 and headed eastwards. Montgomery captured Tripoli in January 1943. Rommel realised the hopelessness of his position given the superiority of the enemy in terms of numbers and logistics, but his recommendation to the German high command that North Africa be abandoned went unheeded. Rommel, who had withdrawn his forces to Tunisia, was ordered to continue the desert campaign as best he could. The Allies were attacked in northern Tunisia and even defeated at the Kasserine Pass in February 1943. The Eighth Army then won the Battle of Medenine (6 March 1943), and Rommel, by then quite ill, returned to Germany in March 1943; he would never fight again in Africa. Allied ground and air forces combined with naval blockades of key ports to definitively drive the Axis powers out of North Africa by May 1943.