Erwin Rommel (1891-1944) was a German field marshal who gained fame as a tank commander in the Fall of France in 1940 and then as the commander of the Afrika Korps in North Africa, where he gained numerous victories. Known as the 'Desert Fox' for his daring tactics, Rommel was obliged to commit suicide when suspected of involvement in the plot to kill the leader of Nazi Germany Adolf Hitler (1889-1945).

Early Life

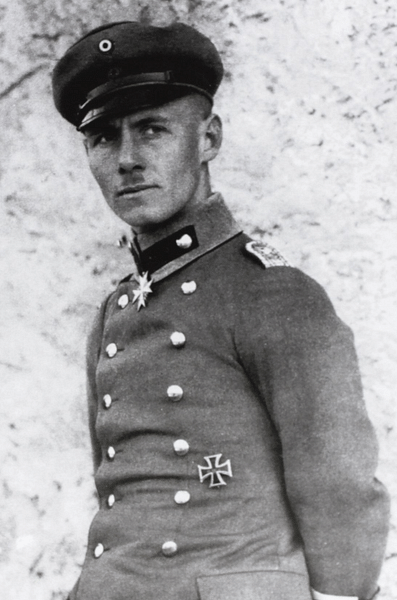

Erwin Rommel was born into a middle-class family on 15 November 1891 in Heidenheim an der Brenz, southern Germany. His father was a mathematics teacher, a subject Erwin showed a talent for when he was not cycling and skiing. Keen to study engineering and perhaps join the Zeppelin airship company, Erwin ended up joining the army in July 1910, specifically, the 6th Württemberg/124th Infantry Regiment. In the German system, future officers joined the ranks to gain their first experience of military life. Rommel earned his sergeant stripes and an insight into the private's life, which would serve him well as a commander throughout his career. Completing his officer's training at the War Academy of Danzig (modern Gdańsk) in early 1912, Lieutenant Rommel served in the infantry regiment he had first joined in 1910.

By the time the First World War (1914-18) broke out, Rommel was a platoon leader. One biographer memorably describes the young officer as "the perfect fighting animal, cold, cunning, ruthless, untiring, quick of decision, incredibly brave" (quoted in Boatner III, 462). During the conflict, Rommel won both the 2nd and 1st class versions of the Iron Cross. He was next assigned to a special group of mountain troops where he served as a company commander. Here he learnt the value of mobility in modern warfare. For his role in capturing Monte Matajur near Caporreto in the Italian Alps in October 1917, Rommel gained another medal, this time the Pour le Mérite (Prussia's highest decoration), one of only two he would proudly wear for the rest of his life, the other being the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds (the highest German decoration). By now a captain, Rommel saw out the war as a staff officer.

Family

Rommel had a daughter, Gertrud, with a fruit seller called Walburga Stemmer in 1913, but the couple were not married, and neither would they be given their differences in social position. He had already met his future wife, Lucia 'Lucie' Maria Mollin, in Danzig in 1911; they married in 1916. Lucie was the daughter of a wealthy landowner and the couple remained close even when separated by two world wars. The letters Rommel frequently wrote, always starting with "Dearest Lu", give a unique insight into the commander's private thoughts regarding his campaigns. The letters, kept out of Nazi hands by Lucie, were posthumously collected into a single volume, The Rommel Papers. Rommel and Lucie had a son, Manfred, born in 1928.

Between the Wars

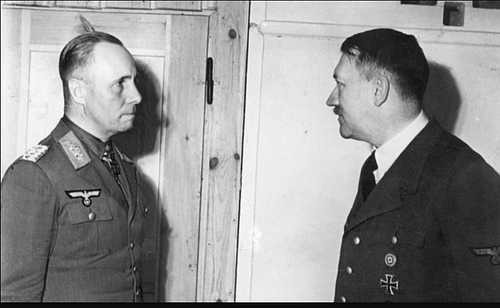

In the interwar years, Rommel continued his military career, notably commanding a mountain battalion and giving dynamic and popular lectures, first at the Dresden Infantry School and then at the Potsdam War Academy. Although never becoming a member of the general staff, Rommel wrote of his knowledge of tactics in his Infantry Attacks (Infantrie greift an). The Swiss were particularly impressed and used the book as one of their army manuals. Hitler also liked the book, and the two men became friends of sorts, Rommel commanding Hitler's personal security detachment from 1938. By 1939, Rommel had achieved the rank of major-general. Seemingly uninterested in Nazi party politics, Rommel was, nevertheless, not so scrupled as to waste his relationship with Hitler, and he secured a choice command in February 1940, that of the 7th Panzer Division. This was just in time for the action to begin in earnest in WWII.

The Fall of France

Germany attacked France in May 1940, and Rommel led his panzers with aplomb, often daringly pressing ahead, ignoring the convention of awaiting infantry support. Rommel won a notable victory at the Meuse, and his division moved so quickly compared to everyone else that it became known as the 'Phantom' division. The port of Cherbourg surrendered to him on 19 June. Rommel raced on to the Spanish border as behind him the chaos led to the collapse of French resistance. The next year, Rommel was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-General in preparation for his next mission: curb the Allied threat in Africa.

North Africa

Following the Allied victories against Italian forces in Operation Compass (ended February 1941), Hitler decided to send German troops to ensure North Africa was not completely overrun. Who controlled North Africa also controlled vital Mediterranean shipping routes and strategic islands like Malta. Hitler's plan, known as Operation Sonnenblume (Sunflower), was intended to be entirely defensive, but the man he chose to lead this new force had other ideas. The Deutsches Afrika Korps, formed in February 1941 and consisting of two armoured divisions, was to be led by Rommel. With close to 30,000 men and over 300 tanks under his command, Rommel believed the best defence was to attack the enemy. In addition, he entertained ideas of pushing the Allies right back into Egypt and even capturing the vital Suez Canal.

Rommel led the Afrika Korps until his promotion in August 1941 when he took command of the wider Axis forces in North Africa, variously named as Panzer Group Africa (September 1941), Panzer Army Africa (January 1942), and then German-Italian Panzer Army (February 1943). Technically, since Libya was an Italian colony, Rommel's superiors were the Italian high command, but he often bypassed this level and communicated directly with Hitler, his relationship with the Nazi leader blossoming after each new victory.

Rommel's Tactics

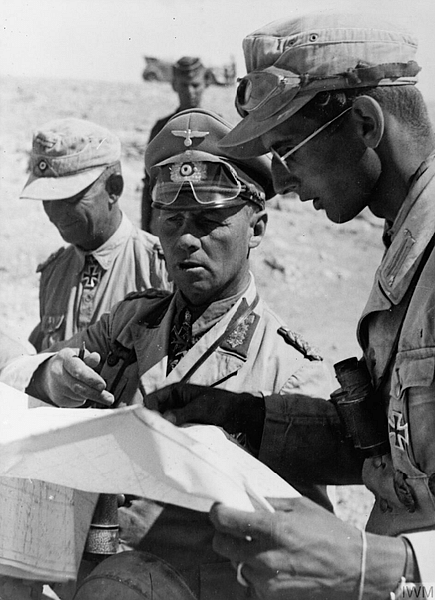

Rommel quickly forged his divisions into formidable fighting units, largely through hard training and sheer personality. As one of Rommel's staff officers noted: "The Afrika Korps followed Rommel wherever he led, however hard he drove them" (Dear, 7).

Rommel instilled in his troops the importance of combining arms for greater effect, deploying tanks, artillery, anti-tank units, and infantry to mutually assist each other and overwhelm the enemy. Rommel proved time and again that anti-tank guns were far more effective against enemy tanks than tanks themselves, the traditional view of how armour should be used. Rommel favoured speed and audacity, attacking in force using combined units to deeply penetrate the enemy lines at a specific point, cutting off units from their reserves and supplies, encircling the enemy, and then destroying material en masse. Meanwhile, Rommel's flanks were protected by reconnaissance forces, and the infantry behind the armour secured the ground just won. Although this aggressive approach often meant victories came at a high cost, these were tactics that greatly unsettled the much more cautious Allied commanders. Even more unsettling, Rommel seemed to have a gift for second-guessing what the enemy would do next, a tactical intuition first noted by his men back in WWI.

Rommel's first victories in Africa came at El Agheila in March 1941 and then Mersa Brega on 1 April, capturing Benghazi on 4 April. The Allied offensives of Brevity and Battleaxe in May-June 1941 were rebuffed, but the siege of Tobruk was a failure (April-December 1941). Rommel gained an important victory at the Battle of Bir Hakeim and his greatest at the Battle of Gazala (May-June 1942), which terminated, at last, with Tobruk's capture. Rommel also won a stunning victory at the Battle of Kasserine Pass in Tunisia (February 1943), which gave the US Army a first bloody taste of desert warfare.

Rommel, more often than not with British maps in his hands and British-made goggles protecting his eyes so that he could read them, charged around the battlefield in a half-track vehicle (his favourite was called 'Greif'), cajoling his officers to greater efforts. Rommel benefitted from excellent military intelligence, with Allied communications being intercepted, revealing their commander's plans.

The Rommel Myth

Rommel became known to his enemies as the 'Desert Fox' in begrudging admiration. Indeed, the Allied high command became increasingly anxious that their soldiers were bewitched with Rommel, who was seen by many as the bogeyman of the desert war, a general capable of extraordinary achievements in extraordinary places. Even Allied commanders respected Rommel. Major-General John Harding states: "Rommel was a brilliant tactician, a great opportunist and a very fine leader on the battlefield" (Holmes, 264). The British prime minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965) described Rommel as "a great general" (Strawson, 253).

Most important of all, Rommel was beloved by his own troops. Even his Italian troops liked the German commander. Captain Behrendt recalls:

Rommel was much loved by the Italian simple soldiers because he cared more about them than anybody else in the desert and they called him 'Santo Rommel' ['Saint Rommel'], I have heard them say this.

(Holmes, 161)

Rommel's 'lead from the front' approach endeared him to his men, as here remembered by one Afrika Korps soldier:

Rommel was one of us, a German soldier with dust on his boots and dirt under his nails. He was the sort of general we all would have wanted to be. He was the type of general we wanted. He was our general.

(Clark, 201)

The Nazi regime was keen to capitalise on Rommel's popularity, and so he was made a field marshal in 1942 in a glittering ceremony in Berlin. At 49 years of age, Rommel was then the youngest field marshal in the German army. Rommel himself contributed to his legendary status, welcoming photographers and always striking the right pose for the press back home.

There were and remain some criticisms of Rommel. He was, for example, not as popular with his superiors as he was with ordinary soldiers. Field Marshal Kesselring (1885-1960) thought Rommel had no talent for anything beyond army level. Rommel irked his superiors because he rarely communicated his plans, and when he did, he more often than not did something entirely different anyway, such was his emphasis on improvisation. Neither did Rommel's immediate subordinates appreciate his habit of moving around the front line away from his command headquarters, which meant communicating with him became difficult. In addition, the general had a volatile temper, was stubborn, did not tolerate any opinion that was against his aggressive tactics, and was utterly ruthless against poor performers or insubordination in his divisions. Some modern historians, too, have been keen to point out that Rommel's successes often came at a time when his enemies were weakened for one reason or another, and that perhaps he was no more gifted than any other competent general of the period.

The Tide Turns

Rommel was very often at a disadvantage in one crucial area: supplies. Dependent on all supplies being shipped from Italy, these resources fluctuated wildly as the Allies used their air and naval dominance to sink Axis supply ships. As Rommel noted in his private letters, "Everything depends on supplies" (Strawson, 225). Rommel would always struggle to gain the resources he wanted to conduct the campaign in his own way, especially after the German invasion of Russia (Operation Barbarossa) from June 1941, which became Hitler's priority. Often, the only solution was to attack and take supplies from the enemy.

As the Allies steadily built up a massive superiority in men and material, so the tide began to turn in their favour. Rommel lost ground at the First Battle of El Alamein (July 1942) and then lost much of his army at the Second Battle of El Alamein where the Allied forces, including the famed 'Desert Rats' were led by the extremely thorough General Bernard Montgomery (1887-1976). Rommel had been absent in the crucial first days of this battle, ill with serious and persistent stomach and nasal problems. Critics, then and since, have cited these defeats as evidence that Rommel was not suitable for a command above divisional level.

The final death bells of Rommel's African escapade rang when the Allies conducted the massive amphibious landings of Operation Torch in November 1942, which squashed the Axis armies into a small pocket around Tunis. Overwhelmed, the Axis armies surrendered in May 1943. By then, Rommel had already returned to Germany due to ill health. Rommel had tried to persuade Hitler that North Africa desperately needed more resources, which would allow him to withdraw his army intact. The field marshal was also keen to return to the men he had led through thick and thin, but, as he himself realised, "All of my efforts to save my men and get them back to the Continent had been fruitless" (Allen Butler, 439).

Normandy Command

After the North Africa surrender, Rommel was appointed Commander-in-Chief Southeast in July 1943 and moved to Salonika. With the overthrow of the Italian leader Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) in the same month, Rommel was moved to command the defence of the Alps, ultimately being appointed the commander of Axis forces in northern Italy in August. The fluidity of the situation in southern Europe and imminent threat of an Allied invasion of northern France meant that Rommel was soon packing his medals and baton again, this time for Normandy.

Rommel's new position was inspector general of the coastal defences along the entire northern European coast from the Spanish border to Denmark, although Normandy was considered one of the most likely areas where an Allied invasion would occur and one of the areas which needed most catching up to make the so-called Atlantic Wall less of a propaganda myth and a practical defensive reality. Rommel, as he had in the desert, invigorated the enterprise, always full of ideas and driving his men hard.

Rommel had half a million steel obstacles strewn across the wide Normandy beaches. 4 million mines were laid. Aware that paratroopers would be involved in any invasion, he had tens of thousands of stakes planted in fields behind the beaches. These stakes, many of which had barbed wire and booby traps attached, were known as 'Rommel's asparagus'.

The real issue was how to best use troops in the defences. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (1875-1953), commander-in-chief of the German army in the West, believed it would be impossible to stop an invasion on the coast and so thought it better to hold the bulk of the defensive forces as a mobile reserve to counterattack against enemy beachheads. Rommel, appointed commander of Army Group B in Jan 1944 (and so in charge of the area from Antwerp to the Loire), disagreed, since overwhelming Allied air superiority, as had been shown in Africa, meant that reserves could be easily destroyed. Rommel, therefore, considered it essential to halt any invasion on the beaches themselves. Hitler settled the issue with a compromise plan that only resulted in a confused command structure. The D-Day Normandy landings in June were a great Allied success. Rommel pushed Hitler for more divisions for this new front, but his ideas were dismissed. Hitler confided in his armaments minister Albert Speer (1905-81), "Rommel has lost his nerve; he's become a pessimist. In these times only optimists can achieve anything" (Speer, 482). The good relationship between führer and field marshal was clearly over.

As the Normandy Campaign swept the Allies through France, Rommel was approached by conspirators who wished to assassinate Hitler and negotiate an honourable peace before Germany itself was invaded. Although he supported the ultimate cause, Rommel did not agree that Hitler should be killed. As the historian P. Caddick-Adams notes, "there is nothing concrete to tell us how close to the conspiracy Rommel really was" (426). Events then quickly spiralled out of Rommel's control.

Forced Suicide

Rommel was seriously injured on 17 July 1944 when three Supermarine Spitfires attacked his staff car. Unconscious for a week, Rommel missed the failed assassination attempt on Hitler (20 July) but was then caught up in the backlash against anyone remotely connected with the conspirators. One key conspirator, General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel (1886-1944) happened to whisper Rommel's name as he regained consciousness from a medical operation, and that sealed the field marshal's fate.

Recuperating from his car crash at the family home in Herrlingen, Rommel was visited by two generals on 14 October 1944. They carried an ultimatum directly from Hitler giving Rommel two choices: face a public trial for treason or take his own life. In the latter case, guarantees were made for the safety of Rommel's family, and he would be given a state funeral with all the honours due a hero of the Third Reich, his reputation intact. Given only ten minutes, Rommel consulted his wife and said goodbye to his son. Driving a short distance from his home, Rommel, dressed in full uniform (the Afrika Korps version) and clutching his field marshal's baton, committed suicide by taking a cyanide capsule. The public were told that Rommel had succumbed to injuries from the car accident back in July. His funeral took place on 18 October in Ulm, there was a military procession, a 19-gun salute, and a large wreath sent from Hitler. Rommel's body was cremated and his ashes buried in Herrlingen.