Crowded and uncomfortable air raid shelters became a feature of the urban landscape across Britain during the Second World War (1939-45) as the bombers of Nazi Germany systematically hit cities from 1940. The London Blitz was a particularly sustained period of bombing which civilians escaped from by diving into private or public shelters when the sirens whined their warning signal.

People sought refuge in the London Underground stations, in purpose-built community shelters, in their cellars, under the stairs, or in refuges in their gardens such as the Anderson shelter. The danger was real, prior to the autumn of 1942, more British civilians were killed in the war than British military personnel.

The Bombing of Britain

Civilians had a lot to put up with even before the bombing started. The blackout was imposed where no non-essential lights were to show at night and so help enemy bombers. There was a real fear that gas bombs would be used, and so everyone was encouraged to carry gas masks. The Phoney War, the period of relative military inactivity in Britain between September 1939 and the spring of 1940, brought a sense of false security, but the German Luftwaffe (air force) would arrive soon enough.

Hundreds of thousands of children were evacuated from cities, including the capital where one million children were shipped out. Youngsters were sent to the safety of the countryside, but the separation from parents and a familiar environment proved traumatic for many. As the historian J. Hale points out: "By January 1940 about half of all children and nine out of ten mothers had returned to their old homes" (27). Despite this, when the bombing started, the official policy of evacuation was continued.

Bombers of the Luftwaffe and the Italian Air Force dropped both explosive and incendiary bombs, the first type to smash through buildings and the second to set the ruins alight. Britain had an integrated air defensive system, the Dowding System, which monitored incoming aircraft and sent out fighters to intercept like the Supermarine Spitfire, but many bombers got through to deliver their deadly loads. In the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe aimed to destroy the Royal Air Force (RAF), both in the air and on the ground, while a secondary aim was to terrorize the civilian population. As the Luftwaffe began to lose the battle, so it concentrated more on civilian targets. Most raids were carried out at night since darkness was the best protection for the German bombers against fighters and anti-aircraft guns. The bombers were guided by radar to their targets, but bombing remained highly inaccurate so that even when strategic sites like factories were the target, there was usually great damage to civilian areas.

London was first bombed on 24 August 1940. The bombers were to attack an oil terminal but mistakenly hit the city, thus beginning a tit-for-tat bombing of civilian areas that escalated to unimaginable horrors like the total bombing of Coventry and Hamburg (Operation Gomorrah). The systematic bombing of London began on 7 September 1940 and continued until the middle of May 1941. The British press called this campaign "the Blitz". The East End of the city, where the docks were located, was a particular target. Other cities across Britain were also repeatedly hit. For civilians, not knowing where the bombers would hit next, air raid shelters became essential everywhere.

The Warning System

The police and Air Raid Precaution (ARP) volunteers (1.6 million around the country, many of whom were women), warned civilians that bombers were headed for their location, information that came from RAF Fighter Command using its network of radars and observers. The whine of air raid sirens became an all too familiar sound during the war. When the sirens went off, it usually meant bombers were just 12 minutes away. ARP wardens made sure people headed to the shelters, compiled damage reports, and alerted bomb disposal squads to any unexploded munitions (UXBs). The public often helped the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) to put out fires using buckets and stirrup pumps. People were informed that a raid was finally over by the sirens ringing a steady note. Most raids lasted most of the night.

The sirens, of course, could ring out at any time and interrupt daily life. John Scott, on leave from his post with Coastal Command, recalls a raid when he was in a London cinema:

In those days, early in the war, when the air-raid siren sounded a notice to that effect would appear on cinema screens, asking those who wanted to go to the shelters to leave quietly. On this occasion we were in a cinema near Victoria station when the manager appeared on the stage and told us that bombs were dropping. A few minutes later we could hear them; everyone rose and headed for the exits. In the streets outside there was chaos – people charging about, shouting, searchlights flashing, guns going off, bombs dropping, and already the glow from fires in the sky over the river. It was very frightening, and there was sometimes a lot of panic before people got used to these mighty raids.

(Neillands, 45)

Eventually, the authorities stopped the sirens in favour of a calmer warning system using the ARP wardens. The people themselves became tired of leaving their homes night after night, and by November 1940, only 40% or so of Londoners were going to the public shelters for refuge.

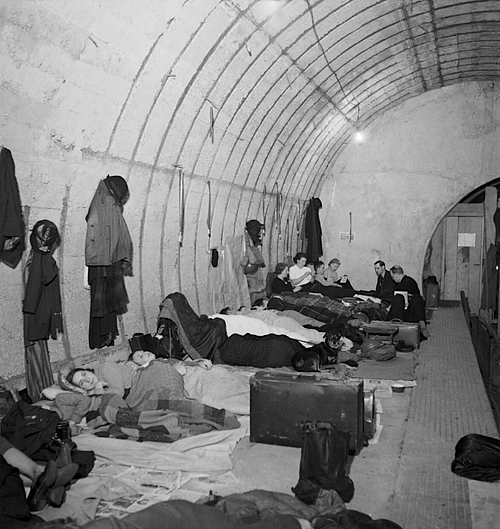

Community Shelters

Britain expected a bombing campaign against it. The terrors of modern air warfare had been displayed all too clearly in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) in which the Luftwaffe had actively participated. One London resident, Mr Overlander, explains:

They expected a tremendous number of civilian casualties, dead, and all the schools and playgrounds were turned into emergency mortuaries with stretchers and things of that sort to put the bodies on. But the thing that surprised the authorities, owing to the policy of the Anderson shelters and things of that sort, was that very few of the people themselves were injured but there was a tremendous damage to property, all these little houses at the least blast fell down.

(Holmes, 140)

The government followed a policy that community shelters were necessary but not to be encouraged since massing many people together would mean greater casualties where the bombs hit. There was even a government booklet, The Protection of Your Home Against Air Raids, which encouraged people to create a 'refuge room' in their house, basement, or coal cellar. A consequence of this policy was that local authorities were delegated to build and organise public shelters. This meant that facilities varied greatly depending on the area. The cellars of such buildings as schools and town halls, railway tunnels and bridges, the perceived sanctity of churches (although crypts were safe enough), and purpose-built street shelters of concrete, bricks, and earth welcomed people each night, not only locals but anyone caught out in the street when the bombers came. "In London alone, at least 5,000 shelters were erected" (Levine, 63). Some street shelters were death traps since councils cut costs and used insufficient cement. Some were so flimsy, dirty, and flooded that they attracted few shelterers. A shelter in Waterloo even had a sign warning people they entered at their own risk. The government had plans for deep underground shelters, but these were not completed until 1944. Businesses were obliged by law to provide some sort of shelter for their workers (who worked day and night shifts) and were given government funds to do so, but, again, the ability of such shelters to withstand bombing varied greatly.

One East End Londoner describes their local community shelter:

The shelter where we used to be what we call 'under the arches' and at the end of under the arches was a bigger archway and there'd be a canteen in there and this was run by Father John Groser of Stepney. He used to run the canteen and run dances so we all used to have half an hour, an hour up there and all. He used to come through selling coffee or cocoa or tea and what have you and keep us all happy in the shelters, it was one big, happy family.

(Holmes, 141)

In the community shelters, people tried to forget the risks to their property above ground and the unsavoury smells and discomfort below. They chatted, played cards and darts, wrote diaries, and tried to put up with the consequences of so many strangers all together in the same place, the whispered prayers, the snoring, and the arguments that developed over breaches of shelter etiquette like putting down one's blanket in another persons's usual spot or stepping on somebody in the darkness. The majority stoically accepted the inconveniences, even developing a spirit of community as faces became familiar and routines were established. The authorities began to get their act together as the Blitz wore on, providing more public shelters with more toilets, washing facilities, canteens, and bunk beds. Much depended on the enthusiasm of the individuals managing a shelter. Some had libraries of their own, like one in West Ham with an impressive 4,000 volumes. Classes were put on and acting troupes toured the official shelters.

Sometimes bombs fell that destroyed shelters or underground venues previously considered safe. The famous Café de Paris, an underground nightclub, promoted itself as the safest nightclub in London. On the night of 8 March, the club was hit by two bombs, only one of which exploded but still killed 32 people. The Kennington Park Shelter in London – a long trench lined with concrete – was struck by a bomb, which killed 47 people. The hit on the Dame's Alice Owen's School in Edmonton was a similar disaster when a parachute bomb collapsed the building and trapped 150 people in the school's basement.

The Underground

Londoners quickly got the idea that the underground stations of the London Tube were a safe place to see out an air raid. Indeed, the underground network had been a place of refuge during the airship raids of the First World War (1914-1918). The government did not encourage this as it could interfere with the normal running of the trains, but people-power made the habit unstoppable as several thousand gathered in each station each night.

One had to bring one's own bedding, there was plenty of noise from chatter and children running about, and the sanitation was limited, but this did not put off over 150,000 people (around 4% of London's population) who chose to spend the nights in the stations.

Even the underground was not immune to bomb damage. Sloane Square Station was hit on 12 November and 37 people died. On 11 January, a bomb hit the booking hall of Bank Station causing the escalators to collapse and a blast wave that swept people sheltering on the platform below into the path of a train. 111 people were killed in the incident.

Anderson Shelters

An Anderson shelter was a cheap and easy-to-build solution for those civilians who did not have a cellar in their homes or lived too far from a community shelter. It is often claimed it was named after John Anderson, Lord Privy Seal, the man made responsible for British civil defence during the war, but actually, it was named after one of its designers, Dr David Anderson (another designer involved was William Paterson). The shelter was composed of two curved pieces of corrugated galvanized steel which were set in a pit with a depth of between 1 and 2 metres or 3 to 6 feet. The roof was then covered with earth and turf (18 inches or 45 cm being the recommended minimum). The shelter measured 6 ft by 4 ft 6 in and was 6 ft high (1.8 x 1.4 x 1.8 m). They were meant to accommodate four people or six at a push. Around two million shelters were distributed free of charge provided one's annual income was below £250 ($17,000 today) with priority given to areas considered most vulnerable to attacks. However, production was halted due to a shortage of steel, a valuable material needed elsewhere in the war effort. There was, at least initially, a problem of uptake, as explained by one East End resident:

Many of the casualties that happened in the early part of the Blitz need not have happened if they had accepted the help and advice of the authorities. There must have been thousands and thousands of Anderson shelters staked up in depots up and down the country where people said they weren't going to have their gardens destroyed.

(Holmes, 140)

The flimsy Anderson shelter did not appear to offer a great deal of protection, but many survived when the buildings next to them did not, and they certainly protected against flying debris. As the historian P. Ziegler states, an Anderson shelter could "resist a 50 kg bomb falling six feet away and a 250 kg bomb at twenty feet" (99-100). One serious design flaw was the lack of drainage and bailing out after a rainstorm became a frequent chore.

People dashed to their garden shelter with pre-prepared bags of essential items and valuable documents like bank books and house deeds. Those keen on preparation bought themselves a siren suit, a sort of boiler suit with lots of pockets for essential items. When the sirens wailed and one had to get out of bed and dash to the garden, a single suit was a lot quicker to put on than normal clothes. The siren suit was championed by Winston Churchill (1874-1965), and there were small sizes for children.

People tried their best to make their Anderson shelters homely as they spent more and more time in them. They fitted their shelter with carpet, pictures (especially patriotic portraits of the monarchy), candles, artificial flowers, and as much furniture as could be squeezed in. Some went for individual beds, others for bunkbeds and chairs. Those who could afford it had a chemical toilet, others simply had a bucket. Time in the shelter could be used to read, knit, or repair things. People listened to wind-up gramophones or, because many were shared between households, caught up on local gossip as to who had survived the last raid.

For those who had neither a cellar nor a garden but still wished to stay in their homes during a raid, there was the possibility of acquiring a Morrison shelter from January 1941. The shelter, named after the Home Secretary Herbert Morrison, was a steel box-table that the family could all lie under. If none of these options was available, the last and most popular resort was to seek refuge under the stairs. A more drastic option was to leave the urban areas and head for a night in the countryside, a phenomenon known as 'trekking'.

The Psychology of the Blitz

The enemy believed that the systematic bombing of London and other cities would destroy the social fabric of Britain. In this, they were quite wrong, if anything, the opposite happened as people pulled together. Even the monarchy became 'one of us' after a corner of Buckingham Palace was hit by a bomb. It is true, though, that there were some strains put upon society.

There were often accusations that some people were using the shelters for improper liaisons. There were other, more sinister prejudices, too, such as rumours that Jews were spending all day in the shelters and taking the best places when there was a raid. The idea that the best-placed spots were being traded in some sort of shelter black market seems to have been widespread, too.

There were, albeit rare, instances of those without shelters acting upon their displeasure at seeing the wealthier elements of society safe in their shelters. In one incident, a crowd pushed their way into the basement of London's swanky Savoy Hotel, then being used as a shelter. The 100-or-so interlopers were led by Peter Piratin, a leading communist, but they were allowed to stay the night. Piratin and his followers were served tea, which they insisted on paying for (although not at the Savoy's usual price).

The authorities were certainly concerned over civilian mental health as well as protecting them physically from the bombing. John Langdon wrote a short guide for maintaining a positive attitude during the bombing, his Nerves versus Nazis. Certainly, many who could left the big cities for the relative safety of smaller towns, staying with relatives. As the destruction affected more people, the monarchy and leading politicians visited bombed-out homes, and the propaganda branch of the UK government put up posters with slogans like "Britain Can Take It".

The End of the Bombing

The Blitz ended in the spring of 1941, with Britain unsubdued. The Luftwaffe had conducted 85 major operations against London and dropped 24,000 tons of high explosives. The losses in aircraft and technological improvements in air defences meant the campaign was halted to prepare for Hitler's campaign against the USSR, Operation Barbarossa (22 June 1941). The bombing of Britain killed over 43,000 civilians, injured another 139,000, and made over 750,000 families homeless, but the skies would darken once again before the war ended when Germany sent almost 10,000 V-weapons, unmanned flying bombs, in the final year of WWII. These attacks caused another 6,184 civilian deaths and injured almost 18,000 more, but how heavier would have been these casualties without the country's system of air raid shelters?