The Matter of Aratta is the modern-day title for a collection of four poems – Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana, Lugalbanda in the Mountain Cave, and Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird – concerning the rivalry between the cities of Uruk and Aratta and dated to the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE).

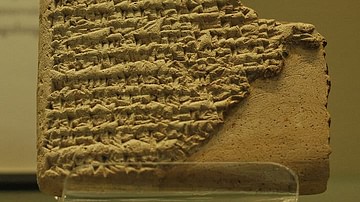

Their order of composition is unknown, and scholars disagree on the order in which they should be read, but they originated in the scribal schools of the city of Nippur, possibly during the reign of Shulgi of Ur (2029-1982 BCE). The popularity of the Matter of Aratta is attested by the number of copies discovered at Nippur and elsewhere beginning in the mid-19th century as well as the style in which they are written, suggesting the hand of highly skilled scribes creating lasting works, not merely scribal exercises.

All four poems were part of the curriculum of the edubba ("House of Tablets"), the Sumerian scribal school, and were included as required texts one needed to master toward the end of one's formal education to graduate. The poems all feature Enmerkar, King of Uruk who, according to the Sumerian King List (c. 2100 BCE), reigned for over 400 years during the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) and founded the city. His successor, Lugalbanda, is the main character in what are usually regarded as the last two poems (sometimes translated as a single work), also known as Lugalbanda I and Lugalbanda II. As they feature historical figures in fictional tales, the works may also be considered Mesopotamian naru literature, the earliest form of historical fiction.

According to some scholars, including Samuel Noah Kramer and H. L. J. Vanstiphout, the works were composed to celebrate Sumerian culture during the period now known as the Sumerian Renaissance when, after the end of the occupation of the region by the Gutians, the Sumerian kings of the Ur III Dynasty revitalized their cultural legacy through building projects, arts, and written works. Today, the four poems of the Matter of Aratta are regarded as among the most impressive in the corpus of ancient Mesopotamian literature.

Background

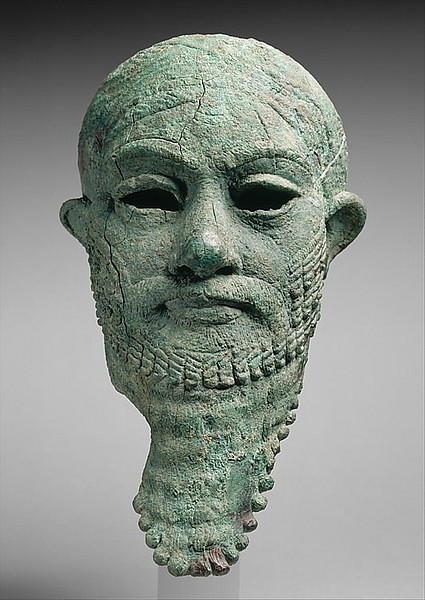

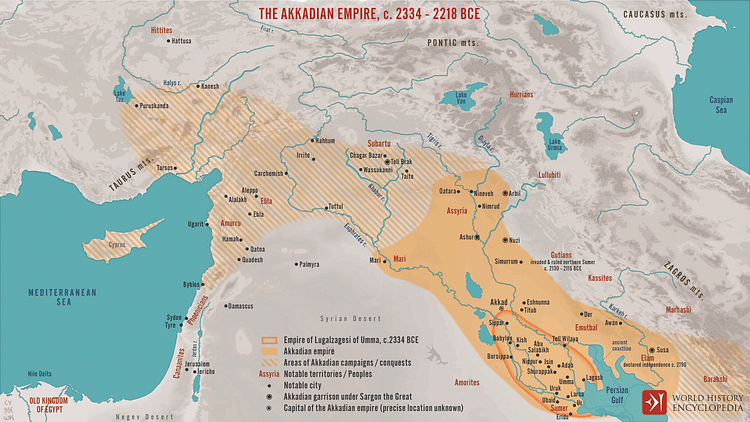

The Uruk Period, which saw the foundation and growth of cities throughout Mesopotamia, was followed by the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) during which Sumerian culture flourished. The city-states were then conquered by Sargon of Akkad (Sargon the Great, r. 2334-2279 BCE) and absorbed into his Akkadian Empire which fell to the Gutians in 2218 BCE. Although the Sumerian city-states had repeatedly rebelled against Sargon and his successors, they found the Gutians far worse overlords, as attested by later inscriptions. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek relates the later Sumerian scribal accounts of the Gutian occupation:

[According to Sumerian scribes], the catastrophe [the Gutians] visited on Akkad was merciless: "Nothing escaped their clutches, no one avoided their grasp. Messengers no longer traveled the highways, the courier's boat no longer passed along the rivers. Prisoners manned the watch. Brigands occupied the highways. The doors of the city gates of the Land lay dislodged in mud and all the foreign lands uttered bitter cries from the walls of their cities." (130)

It is possible, as Kriwaczek and others have noted, that these accounts are poetic fiction exaggerating and dramatizing the fall of Akkad whose decline may have been due more to climate change, drought, and famine than any invasion. It seems, however, that the Gutians were unable to establish a stable government – their king list shows a rapid succession of monarchs – and so something like the chaotic image of the time given by the Sumerian scribes may have been the result.

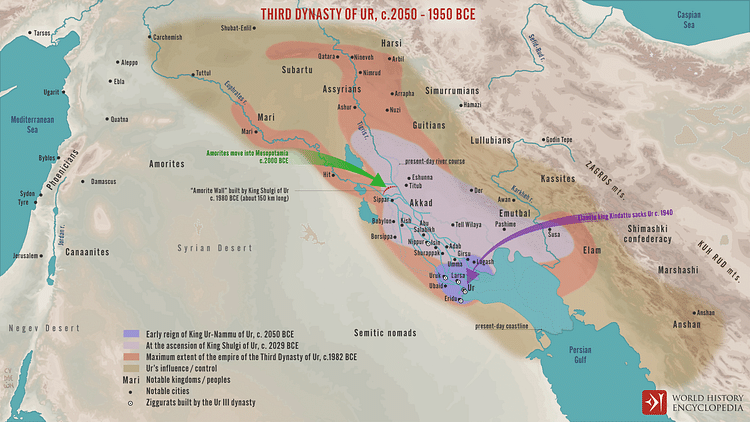

The Gutians were challenged by Utu-Hegal, king of Uruk (r. 2055-2047 BCE), and after his death by Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE), founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur and father of Shulgi of Ur, who succeeded him. Ur-Nammu and Shulgi of Ur drove the Gutians from Sumer, and, afterwards, Shulgi commissioned works and initiated policies honoring his father (who died fighting the Gutians) and reviving Sumerian culture. The poems of the Matter of Aratta are thought to have been composed at this time to celebrate the House of Uruk and link the Ur III Dynasty with an ancient and illustrious past.

The Matter of Aratta

Aratta is depicted in several Sumerian poems, pre-dating the Matter of Aratta, as a city of fabulous wealth which lay far beyond the boundaries of Sumer. Modern-day scholars tend to place it somewhere in ancient Elam, past Susa (in modern Iran). In the poems of the Matter of Aratta, it can only be reached by traversing over seven mountains and is a treasure trove of gold, lapis lazuli, silver, and other valuables.

The Matter of Aratta concerns Enmerkar's efforts in forcing the king of Aratta to submit to him and send him the precious materials he needs to adorn the temple of the goddess Inanna at Uruk. Inanna, in the first poem, lives in Aratta but secretly favors Enmerkar and would prefer to move to Uruk. It is suggested she will do so if Enmerkar can build her a beautiful home.

Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta

If one reads the Matter of Aratta beginning with Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, the problems start when Enmerkar wants to beautify the temple of Inanna with materials from Aratta. He asks Inanna what to do and she suggests he send a message to Aratta demanding the materials he needs. Enmerkar casts "the spell of Nudimmud" (the spell of Enki, god of wisdom) which allows everyone, no matter what language they speak, to understand everyone else. He then sends his messenger ("eloquent of speech and endowed with endurance"), who has memorized his words precisely, across the seven mountains with his demands.

The Lord of Aratta refuses to submit to Uruk and sends the messenger back with a challenge: he will consider submission if Enmerkar can send him grain in nets instead of bags. Enmerkar considers the riddle and has his servants wet the grain down and place it in finely woven nets so none can fall out. The messenger then delivers the grain to Aratta.

The Lord of Aratta then demands Enmerkar deliver him a scepter made of no known substance. Enmerkar spends years perfecting a material he pours into a hollow reed-mold, and after he breaks the reed open, sends the scepter to Aratta.

The Lord of Aratta, still unsatisfied, sends the messenger back asking for a champion of no known color who will be sent to fight his champion. Enmerkar weaves a cloth of lion skin for his champion and sends him to Aratta.

When the Lord of Aratta still will not yield, Enmerkar delivers a long rebuke to his messenger who claims it is too difficult for him to remember. The king then takes a reed stylus and a piece of clay and writes his message – thereby inventing writing – which is sent to Aratta. When the Lord of Aratta receives the tablet, he is thrown into confusion by the written word and submits to Enmerkar. A rainstorm, sent by Inanna, ends the drought in Aratta, and the goddess, while refusing to forsake Aratta, embraces Enmerkar, uniting the two cities in peace as trade partners.

Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana

As the story opens, En-suhgir-ana, Lord of Aratta, claims he is the favored lover of Inanna, and Enmerkar of Uruk rebukes him, claiming the same for himself. En-suhgir-ana insults Enmerkar as a poor lover and Enmerkar sends word across the mountains for Aratta to submit to him. En-suhgir-ana refuses, even though his assembly of elders chastises him for starting trouble with Uruk and urges him to end the argument before it escalates.

A visiting sorcerer, Urgirinuna, makes his way to the court and tells En-suhgir-ana he can cast a mighty spell that will force Uruk to submit to him. The king pays him, promising more when he is successful, and Urgirinuna makes his way to the city of Eresh, sacred to the goddess of writing, Nisaba, and close to Uruk, where he casts a spell that kills the dairy-producing livestock, of all shapes and sizes. The keepers of the livestock pray to Utu-Shamash, god of the sun and justice, for help, and the sorceress Sagburu appears to challenge Urgirinuna.

Urgirinuna and Sagburu meet at the Euphrates River, where he throws in fish eggs and produces an animal, but each time Sagburu does the same, and a predator appears to devour Urgirinuna's creature. Urgirinuna recognizes he is no match for Sagburu and begs for his life, but she refuses, telling him he has already caused harm and will no doubt do so again. She kills him and throws his corpse into the river. When En-suhgir-ana receives word of the defeat, he submits to Uruk.

Lugalbanda in the Mountain Cave (Lugalbanda I)

As the poem begins, Enmerkar demands various precious materials from Aratta to adorn the temple of Inanna in Uruk. He grows tired of Aratta's refusal and mobilizes his army to march on the city. His eight commanders are brothers, and the youngest is the noble Lugalbanda, known for his piety. As they march across the mountains, Lugalbanda falls ill. There seems no reason for the sickness and no cure, but the army must move on, and so, leaving him with food and water, his brothers march off with the others.

For two days, Lugalbanda prays for deliverance to Inanna, Shamash, and the moon god Nanna – deities he has faithfully served all his life – and they restore his health. He goes hunting, but instead of taking the food for himself, he prepares a feast for the gods and offers it to them. The gods are pleased and suggest that Lugalbanda will be elevated above others from now on.

Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird (Lugalbanda II)

The story continues from the end of the previous work with Lugalbanda resting in the mountain cave. He has been restored to health but has no idea where he is or how to rejoin the army. The mountain regions are the home of the great Anzud Bird, so huge that the beating of its wings cause storms and whose breath is fire. Lugalbanda is not eager to meet up with the bird but feels he has no choice if he wants to find his way and so goes looking for its nest.

When he finds it, the nest has fallen into disrepair and the bird's offspring is hungry, as the Anzud has been out for a long while herding cattle. Lugalbanda restores and improves the nest and feeds the young bird, and when the Anzud returns, he is so grateful that he offers Lugalbanda any wish he desires. He tempts the young soldier with riches and power, but all Lugalbanda asks for is speed and stamina, which is granted.

The Anzud helps Lugalbanda locate the army and returns to his nest after telling him not to let anyone know of his new powers. Lugalbanda quickly rejoins the troops and finds Enmerkar in a state of despair. The king is about to abandon his siege of Aratta and has lost faith in his mission. He needs to know whether Inanna still supports him, but the only way to ask her is to return to Uruk and speak with her at her temple - and Uruk is far away.

Lugalbanda volunteers to go alone back to Uruk and, using his new power, arrives there the next day. Inanna tells him she still supports Enmerkar and gives him instructions for the king to cut down a tamarisk tree he will find by the river and catch a certain fish to sacrifice, and then Aratta will fall to him. The tablet breaks off after a description of Aratta and praise for Lugalbanda, but it is suggested that his mission is successful and Enmerkar is victorious.

Conclusion

Lugalbanda is best known today as the father of the hero Gilgamesh and husband of the goddess Ninsun from The Epic of Gilgamesh. In that story, Gilgamesh begins as a proud and haughty king who must learn humility through the loss of his friend Enkidu, but, in these tales, Lugalbanda is depicted from the beginning as a devout servant of the gods who already understands his place in the world at a young age. Instead of crying out in anger or despair when he becomes sick for no reason, he expresses gratitude to the gods and asks for their help, and, even though he is afraid of the Anzud, he seeks its assistance and provides for its young.

Lugalbanda and Enmerkar, both of whom appear in the Sumerian King List as historical (although their reigns are impossibly long), are depicted here as admirable characters who choose peaceful means to reach their ends until, in the case of Enmerkar, those options are exhausted. The Sumerian King List gives no details of what the historical Enmerkar and Lugalbanda were like – if they existed at all – but their depiction in the Matter of Aratta is precisely how the kings of the Ur III Period wanted to be seen by their subjects.

Ur-Nammu presented himself as a father figure to his people. His laws, the Code of Ur-Nammu, were issued to prevent possible problems and enable his subjects to live together peacefully. Shulgi of Ur continued his father's policies, completing the Great Ziggurat of Ur, improving roads, temples, cities, and encouraging literacy through the establishment of more schools. Perhaps, it is thought, the Matter of Aratta was written to link these kings to a greater past, even if that past never existed, when rulers sought peaceful resolutions to conflicts and spared their subjects the horrors of war. Vanstiphout comments:

[In these stories], military glory is spurned and even somewhat ridiculed in at least two of the poems. Instead, the emphasis is on cultural and technical prowess, expressed as the highest form of intelligence and, of course, including writing. Furthermore, they overtly prefer their dominant position to be based on peaceful coexistence, even friendly relations with the outer world, to brute strength. Their ethical principles are founded in respect for and the fostering of the vital forces as such and in all their aspects. Their attitude to the gods is practical and far from naïve. Whatever they achieve, they achieve by their own intellect and craftsmanship, whereas the gods, at most, give moral support…the kind of world and society [the Sumerians] have envisioned in these poems, in an obviously idealized way, is therefore indeed a kind of fairy-tale, pastoral universe. Their assumption is that [Uruk's] domination of that world will be beneficial to all, and that statecraft and rulership should be used to that end. (15)

It is unclear, after all, whether Aratta falls through an assault or surrender as Inanna only tells Lugalbanda that Enmerkar will have victory. In Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, the conflict between the two cities is resolved without bloodshed, and in Enmerkar and En-suhgir-ana magic is used, and it has even been suggested that the figure of Sagburu is the incarnation of the goddess Nisaba, giving divine approval to the contest with Urgirinuna. Throughout, the poems advocate for another approach to political conflict than violence, and even if this may have been or is considered unrealistic, it is still an admirable vision.