The Battle of Sobraon on 10 February 1846 was the last of four major victories for the British East India Company (EIC) against the Sikh Empire during the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-6). Lieutenant-General Sir Hugh Gough (1779-1869) commanded the largest army yet seen in the campaign and, despite heavy losses in attacking the Sikhs' well-fortified positions, won the battle and with it the war.

The EIC & the Sikh Empire

By the mid-18th century, the British East India Company had started to look very much like the colonial arm of the British Crown in India with its territorial expansion across the subcontinent. The Company had won vital encounters with rival powers like the 1757 Battle of Plassey and the 1764 Battle of Buxar, which gave the British a vast and regular income in local taxes, besides other riches. The EIC kept on expanding and defeated the southern Kingdom of Mysore in the three Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799). Intertwined with those wars was a long-running contest with the Maratha Confederacy of Hindu princes in central and northern India. The EIC once again emerged victorious after the three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1819). Next came expansion in the far northeast and more victories in the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814-1815) and what turned out to be three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824-1885). The next and final target of the EIC was northwest India and the Punjab.

The Punjab, located in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, is an area which today covers parts of Pakistan and India. It was the heartland of the Sikhs, who had established a state of sorts in the 18th century following the gradual decline of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857). Sikh territories were divided between 12 misls or armies, each led by a chief who collectively formed a loose confederation. The greatest of Sikh leaders was Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), the 'Lion of Lahore'. He forged the Sikh Empire by modernising the army and conquering Multan and Kashmir (1819), Ladakh (1833), and Peshawar (1834). This expansion rang alarm bells in the offices of the East India Company, especially after their failure in the First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-42) to the north. In 1839, the Sikhs, Afghans, and British signed a treaty to protect existing borders. Ranjit Singh died in June 1839, and political turmoil weakened the Sikh government's control over its own army. Rajit Singh's youngest son, Duleep Singh (l. 1838-1893), was selected as the new Sikh ruler in 1843, but as he was but a child, his mother, Jind Kaur (aka Rani Jindan, d. 1863), ruled as regent. Jind Kaur supported a military escapade against the British since, even if the Sikhs lost, this would cut the army down to size, perhaps ending the interference of the generals in government affairs and certainly reducing the threat of a military coup.

The EIC noted with interest this weakening of the Sikh state and took the opportunity to take over the Sindh province (southwest of the Punjab) in 1843. Confident that some of the Sikh misls in the east supported closer ties with the EIC, the British prepared for war in the Punjab and amassed an army of 40,000 men to the southeast of the Sikh state. In the wider world of empires, the British no longer considered the Sikh Empire a useful buffer zone in case of expansion of the Russian Empire into Afghanistan and northern India – the so-called Great Game. To retain their independence, the Sikhs would have to wage war against the most formidable military force in India: the armies of the East India Company.

The First Anglo-Sikh War

The First Anglo-Sikh war broke out when a large Sikh army crossed the Sutlej River into EIC territory on 11 December 1845. The first confrontation was the Battle of Mudki on 18 December. The EIC was victorious there and again at the Battle of Ferozeshah on 21-22 December. There were so many casualties on both sides, Ferozeshah was a marginal victory only and then largely because the Sikh commanders, with one eye on a post-war regime change, did not apply themselves to the task and refused to go on the offensive. The Sikhs did inflict some serious damage when a British column passed too close to the fort of Bhudowal on 21 January. The EIC army had been treacherously guided to within firing range of the Sikh artillery and suffered a bad mauling. Major-General Harry Smith (1787-1860) then commanded an EIC army to victory at the Battle of Aliwal on 28 January 1846. This left just one Sikh army south of the Sutlej to be dealt with, the final act of this short and bloody war.

The Two Armies

The armies of the EIC had enjoyed a string of victories thanks to its winning combination of British troops, regular British army regiments, sepoy (Indian) and Gurkha (Nepalese) infantry, cavalry, and well-trained artillery units. The principal weapon was the musket, either breech-loaded or the more modern version with a quicker cap-ignited mechanism. The preferred tactic remained, though, the infantry charging at the enemy with fixed bayonets. The EIC commander-in-chief was Lieutenant-General Sir Hugh Gough, a crusty old veteran who led from the front. Gough took command of the EIC army at Sobraon, just as he had at the Battle of Ferozeshah. The British total force numbered some 20,000 men with 32 cannons.

The Sikh army, known as the Khalsa, was as well-trained as the EIC army, thanks to the employ of European mercenaries. It was also well-equipped (although its cap-ignited muskets were inferior replicas) and had far more and bigger cannons than the EIC was able to mobilise in this part of India. These monster cannons were dragged to the battlefield using huge teams of bullocks and elephants. A typical Sikh army brigade was composed of around 3,000 infantry, 1,500 cavalry, and 35 cannons, making them efficient, compact, and mobile fighting units.

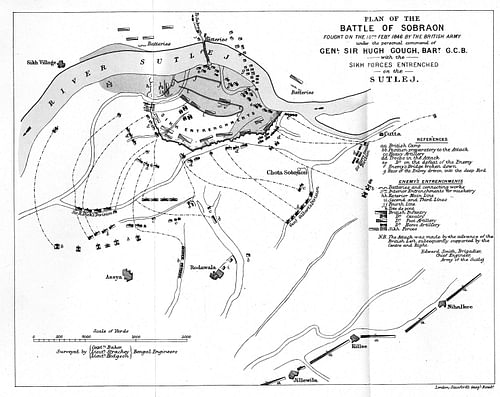

The commander-in-chief of the Sikh Empire's army was Tej Singh (1799-1862), a leader of experience and ability, but in charge at Sobraon was General Ranjodh Singh (aka Ranjur Sing, d. 1872). Ranjodh Singh was one of the few top Sikh commanders loyal to the cause, but he was not a particularly gifted military leader, and he had disgraced himself at Aliwal by leaving half his army to face the British in a chaotic retreat. Ranjodh Singh commanded at least 20,000 infantry, 1,000 cavalry, and around 70 cannons at Sobraon. Through January, excellent defensive positions had been prepared, which covered a total length of 1.8 miles (3 km), and these were occupied following the defeat at Aliwal.

Battle Lines

The two armies met near the banks of the Sutlej river. The military historian R. Holmes gives the following description of the Sikh defences at Sobraon:

... they hold a strong position facing southwards. It is shaped like a long, flattish letter U, a mile and a half wide along its southern side, with an open end to the river, and a pontoon bridge behind it. A Spanish officer in the service of the Sikhs has designed formidable defences, consisting of two concentric lines of earth ramparts, twelve feet high in places, with arrowhead bastions jutting out in front of the embankments and a broad ditch in front of them. On the Sikh right the ground is too sandy for the construction of high ramparts, and on those lower earthworks - too unstable to bear the weight of proper artillery – the Sikhs have placed a line of 200 zumbooruks, light swivel guns usually fired from a camel's saddle. (7)

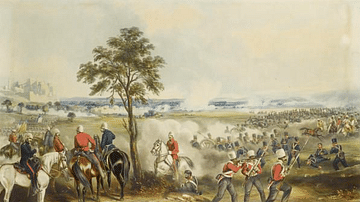

The battle commenced early in the morning of 10 February with the usual exchange of artillery fire. EIC Bombardier Nathaniel Bancroft describes the scene:

The action commenced by a salvo from the guns, howitzers, mortar and rocket batteries. Such a salvo was never heard in the length and breadth of India before ... and the reports of the guns were distinctly heard by the wounded in the hospital at Ferozepur, five and twenty miles away ... [It] was raining a storm of missiles which boomed, hissed and hurtled through the air onto the trenches of the Sikhs.

(Holmes, 8)

The EIC gunners, with their long hours of training and rapid and accurate firing, were used to gaining the upper hand against an enemy, but the Sikh gunners were equally skilled, perhaps even better, since they won the initial artillery duel. The British were obliged to reduce their bombardment as their ammunition ran low (and they needed to keep some back to protect their own infantry charge later on). Gough had also misjudged their position and should have moved the units much closer to their targets to be more effective. The commander was reluctant to do so as this would have brought the British cannons within range of their Sikh counterparts, but as it was, the distance left was too great to do much damage to the defenders. General Gough was likely not too displeased at the lack of progress of the artillery since he always preferred to engage his infantry with fixed bayonets as soon as possible in a battle. The old general, on being informed the British cannons must cease their barrage, is reported to have exclaimed: "Thank God! Then I'll be at them with the bayonet" (Smith, 82).

Some of Gough's officers believed that the Sikhs were so well dug in regarding their defences that it would be better to treat the engagement as a siege and proceed more cautiously. These officers felt that a more concentrated attack at a specific point would gain better results and fewer casualties, but Gough was adamant about a full infantry charge on a wide front.

Attack

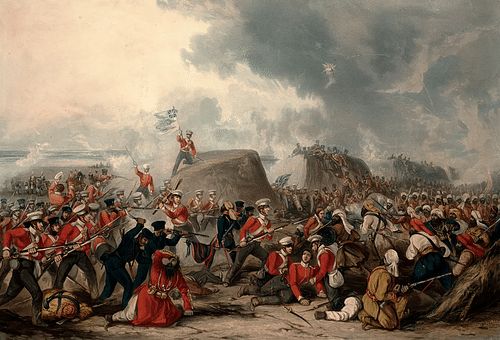

Gough split his force into three, with the two groups in the centre and right feigning an attack to distract the Sikhs while the real attack was being carried out on the left (as viewed from the EIC perspective of the battlefield), the weakest part of the Sikh defences (their right flank). At dawn, the EIC infantry moved through the rising mist of the battlefield towards the Sikh positions. The strategy did not work since the Sikhs focused their counterattack where it was really needed and ignored the feints. The relentless waves of infantry, though, did eventually achieve their objective as they overwhelmed the defensive positions. This progress came at a high cost, as here summarised by an eyewitness dragoon, John Pearman:

Oh what a sight to sit on your horse, to look at those brave fellows as they tried several times to get into the enemy's camp, and at last they did, but oh, what a loss of human life. God only knows who will have to answer for it.

(Holmes, 10)

The same attack, seen from the Sikh side, is described by a gunner, Hookum Singh:

Nearer and nearer they came, as steadily as if they were on their own parade ground, and in perfect silence ... At last the order came, 'Fire', and our whole battery as if from one gun fired into the advancing mass. The smoke was so great that for a moment I could not see the effect of our fire ... what was my astonishment, when the smoke cleared away, to see them all still advancing in perfect silence, but their numbers reduced to about one half ... but on they came, in that awful silence.

(Holmes, 11)

Gough now ordered the two groups conducting the feint attacks to attack the enemy in reality, even if this was at the strongest points of the Sikh defences. Gough was fully aware of this as he had used a purpose-built observation post giving him a clear view of the entire Sikh defences prior to the battle. The Sikh right wing, with the sandy ground and a total absence of Sikh artillery, along with a gap to the river where only cavalry protected the Sikh camp, made for a tempting target, but the Sikhs were now heavily reinforcing this flank. Even worse, the two feint-turned-real attack groups were getting bogged down. Indeed, one of the attack groups faced such high defensive walls they needed scaling ladders to surmount them, a point that only became evident when near the walls. With their progress impeded and a withdrawal back through heavy enemy fire not an option, the British entrenched themselves in the riverbank as best they could to await support. Fortunately for the British, the Sikh cannons had by now sunk into the soft ground of their positions, and the gunners could not lower their angle of fire to hit the enemy now it was so close. Reinforced by more waves of infantry arriving, the British and sepoy units fought a vicious hand-to-hand battle with the Sikh defenders.

After 30 minutes of chaotic and bloody fighting – what one soldier described as "a brutal bull-dog fight" (Bruce, 187) – the EIC force made it over the ramparts and planted the regimental colours flag atop the earth walls. The Gurkha units here performed particularly well with their kukri long knives. The British cavalry, including dragoons, followed up the infantry and caused the Sikh defenders to disperse in small groups, even if some stayed to fight where they stood with slashing swords.

The bulk of the Sikh army was now in retreat – none offered a surrender – but the way back was now blocked by the Sutlej river, which had risen alarmingly in the night because of heavy rains upriver. There was a single bridge which allowed men to cross, but this soon collapsed due to the heavy traffic, and it was swept away by the current. Many men drowned in a desperate attempt to reach the safety of the far bank as the British horse artillery and infantry, remembering the brutal Sikh treatment of their own wounded earlier in the battle, fired at them from the water's edge. By midday, the battle was won. Robert Crust describes the battlefield:

It was an awful scene, a fearful carnage. The dead Sikh lay inside the trenches – the dead European marked too distinctly the line each regiment had taken, the advance ... Flames were spreading over the Sikh camp, igniting the powder beside each gun and the air was rent with terrific explosions. The guns were now nearly all removed and our dead were being buried. We rode slowly home.

(Bruce, 190-1)

The Sikh army had suffered 8-10,000 fatalities. The EIC army suffered 320 men killed and 2,063 wounded. General Gough was made a Baron and given a handsome pension for his victory, but questions remained as to why, not for the first time, he had been responsible for excessive casualties by attacking the enemy defences at their strongest point.

Aftermath

The Battle at Sobraon ended the war as the British army crossed the Sutlej river and marched into the Punjab. Under the Treaty of Lahore, signed on 9 March, the EIC established the Punjab as a 'sponsored state', and parts of the Sikh Empire came under direct EIC rule. The EIC received a massive indemnity payment; they also took over Jammu and Kashmir (as part payment of the indemnity).

Unrest lay beneath the surface, though, in the Punjab. Certain Sikh chiefs felt they had been let down by their generals in the field during the first war (which indeed they had been), and they wanted a second crack at the British. Given the crushing terms of the Treaty of Lahore, the Sikhs had little to lose but potentially much to gain in another war. The Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9) began in April 1848 and was largely fought in the south and west of what had once been the Sikh Empire. Once again, it was a short and bloody campaign with one siege and three major battles, including the Battle of Chillianwala on 13 January 1849, which resulted in high losses on both sides. The EIC was victorious yet again in this war. The whole of the Punjab was annexed in March 1849, and the EIC now reigned supreme in India.