A great deal has been written about why the prehistoric monument of Stonehenge, in Wiltshire, southern England, was constructed. Perhaps it was designed as a temple to the ancestors, an astronomical calendar, a healing centre or a giant computer? Could it even have functioned as all of these things at various stages during its 1500 year history? How our ancestors constructed the great monument has also attracted huge amount of attention over the years. Indeed a number of carefully organized experiments have been carried out at Stonehenge to discover exactly how the Welsh bluestones and local sarsen stones were transported to Salisbury Plain and what method was used to erect them once they arrived at the site.

All this is fascinating enough, but Stonehenge still maintains its less explored, darker aspects, not least of which are the enigmatic burials scattered in and around this famous Neolithic monument. What can these burials, both cremation and inhumation, tell us about the rituals and activities that went on at Stonehenge more than four millennia ago?

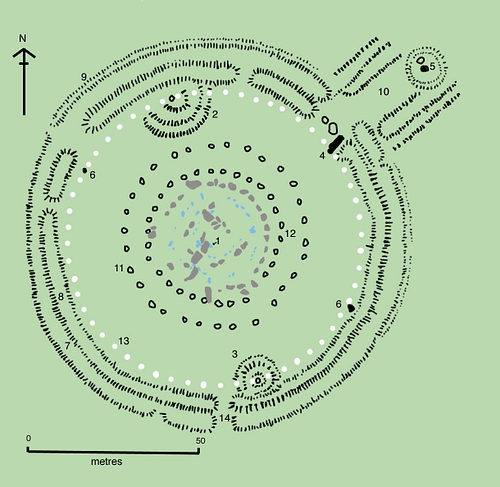

What modern visitors see when they visit Stonehenge is a circular setting of large standing stones surrounded by earthworks, the remains of the last in a series of monuments constructed on the site between c. 3100 BCE and c. 1600 BCE. During its 1500-year history, Stonehenge was built in three broad construction phases, though there were numerous sub-phases in between, and there is evidence for human activity on the site both before and after these dates.

The first monument on the site, began around 3100 BCE, was a circular 'henge' earthwork about 360 feet (110 metres) in diameter, a 'henge' in the archaeological sense being a circular or oval-shaped flat area enclosed by a boundary earthwork. This structure probably contained a ring of 56 wooden posts (or possibly an early bluestone circle), the pits for which are named Aubrey Holes (after the 17th century local antiquarian John Aubrey). Later, around 3000 BCE (the beginning of Stonehenge Phase II), some kind of timber structure seems to have been built within the enclosure, and Stonehenge functioned as a cremation cemetery, the earliest and largest so far discovered in Britain.

The Cremation Cemetery

During the 20th century CE nearly 60 cremation burials were uncovered at Stonehenge, with perhaps a couple of hundred more remaining in unexcavated areas of the monument. Interestingly, the latest of these cremations has been radiocarbon dated to c. 2300 BCE, which illustrates that cremation was still being practiced at Stonehenge long after the bluestones and sarsens had been erected.

Another interesting and unusual aspect of the cremated remains discovered at Stonehenge is that the majority of them are from adult males, most within the 25 to 40-year age group. The conclusion can only be that only certain people were selected for burial within this early Stonehenge monument. These men would have been politically important, perhaps aristocrats and / or clan leaders and were probably authority figures at the site during the first half of the third millennium BC.

Most of the remaining (inhumation) burials in the area of the monument are roughly contemporary with each other, dating from the 2400 - 2150 BCE (the Early Bronze Age period), although there is only one complete skeleton from amongst them. Examination of this intact skeleton, which was found in 1978 CE buried in the outer ditch of the monument, revealed that the man had been shot at close range by up to six flint-tipped arrows, probably by two people, one shooting from the left the other from the right. Could this have been an execution or perhaps even some form of ritual human sacrifice?

The Amesbury Archer - King of Stonehenge?

The Amesbury Archer Burial near StonehengeThe richest of the burials associated with Stonehenge, and the wealthiest ever discovered from Bronze Age Britain, was found amidst Roman graves at Amesbury, 5km (2 miles) south-east of the monument. This high status burial, known as either the 'Amesbury Archer' or the 'King of Stonehenge', and dated between 2400 and 2200 BCE, yielded an astonishing array of grave goods for the period.

Found alongside the skeleton were five 'Beaker' pots, sixteen beautifully-worked flint arrowheads, boar's tusks, two sandstone wristguards (to protect the wrists from the bow string of a bow and arrow), a pair of gold hair ornaments, three tiny copper knives, a kit of flint-knapping and metalworking tools, and a shale belt ring. The discovery of such rich grave goods with this burial indicates a high-status individual who was also probably one of the earliest metalworkers in the islands.

Fascinatingly, chemical analysis showed that one of the Archer's copper knives was of Spanish origin and the gold may also have come from outside Britain. Studies of the skeletal remains by Jackie McKinley of Wessex Archaeology revealed that the Archer was a strongly-built man aged between 35 and 45, though he had an abscess on his jaw and had suffered an accident when young which had torn his left knee cap off. Thus for much of his life the 'Archer' would have walked with a pronounced limp.

But the most surprising element of the Archer's story was yet to come. Research using oxygen isotope analysis on his tooth enamel found that he had grown up in the Alps region, either Switzerland, Austria or Germany. The Archer is thought to have come to Britain at a very young age – perhaps when a child. Why did he travel such a long distance? Was it perhaps to seal an alliance between distant peoples? Or did he possess some kind of 'magical' skills (the 'mystical' new art of metalworking perhaps?) which were believed to be necessary in the building of Stonehenge?

Flint Arrowheads found with the Amesbury ArcherIf the latter is true, perhaps the unusually rich burial of the 'King of Stonehenge', obviously an important person of high rank, means that he played an important part in the construction of the first stone-built monument on the site.

Interestingly, a second burial, dating from the same period as the Archer, was located near to his grave. This skeleton, that of a male aged around 20-25, which bone analysis has shown to be either the Archer's son, brother or cousin, had been buried with a pair of gold hair ornaments in the same style as the Archer's, though for some reason these had been left inside the man's jaw. Oxygen isotope analysis revealed that this man had grown up in the area around Salisbury Plain, though his late teens may have been spent in the Midlands or north-east Scotland. These fascinating burials obviously represent important people, but were they kings or priests of some kind, or perhaps members of a local ruling clan or family?

The Boscombe Bowmen

The 'Boscombe Bowmen' are a group of Early Bronze Age burials (dated to about 2,300 BCE), found in a single grave at Boscombe Down, an aircraft testing site south of Amesbury. Known as bowmen due to the amount of flint arrowheads found in their grave, the burial consists of seven individuals: three children, a teenager and three men, all apparently related to each other.

Finds from the grave are similar in character to that of the Amesbury Archer and included an unusually high amount of Beaker pottery, flint tools, a boar's tusk and a finely worked bone toggle. Again it was chemical testing on the teeth that provided the clue as to where these people originated, in this case the men grew up in Wales but migrated to southern Britain in childhood. A British origin for the Bowmen is interesting, considering the continental nature of many of their grave goods (the Beaker pots decorated with plaited cord, the bone toggle). It surely cannot be a coincidence that one of the few parallels for such grave goods in Britain is the nearby burial of the Amesbury Archer.

The Stonehenge Burials by Brian HaughtonGiven that the Boscombe Bowmen were roughly contemporary with the transport and erection of the Welsh bluestones at Stonehenge it is believed by many researchers that they may have accompanied the stones on their 300 km (186 miles) trek to Salisbury Plain from south Wales. Considered together, the burials of the Amesbury Archer and the Boscombe Bowmen offer fascinating evidence not only for people who may have been involved in the task of designing and constructing Stonehenge, but also for close ties between Britain and continental Europe more than 4200 years ago.

The Boy with the Amber necklace

A further sensational burial at Stonehenge came to light in September 2010 CE, though the grave had originally been discovered in 2005 CE. Nicknamed 'the Boy with the Amber necklace', the skeleton again came from Boscombe Down, but this time belonged to the end of the Early Bronze Age (it was radiocarbon dated to around 1550 BCE).

The skeleton, which was discovered next to a Bronze Age barrow (burial mound), was of a 14 or 15 year-old boy had been buried wearing a necklace of around 90 amber beads. Amber necklaces are rare and exotic objects; the amber would have been brought to the Stonehenge area from the Baltic Sea, perhaps Denmark, and may have arrived as lumps of raw material before being fashioned into tiny beads locally.

Close examination of the skeleton revealed another astonishing fact. When Professor Jane Evans, Head of Archaeological Science at the British Geological Survey, analysed tooth enamel samples from the teenage boy, she discovered that he was not local. Far from it. Professor Evans' results showed that the Boy with the Amber necklace had in fact grown up in a much warmer climate than Britain, probably the Mediterranean. But what was he doing at Stonehenge? The necklace suggests the boy was a person of significant status and importance, but little else.

One theory is that the boy travelled as part of a family group on some kind of pilgrimage to Stonehenge, even though the great monument was already 1500 years old at this time.

Was the boy's family perhaps involved in the last known construction phase in the history of Stonehenge (in the 16th century BCE), the Y and Z Holes? These mysterious features, two rings of concentric circular pits cut around the outside of the Sarsen Circle, are of unknown origin and function and have long puzzled archaeologists. Unfortunately, without more in depth analysis of the Amber Boy's skeleton and more finds from contemporary burials, it is impossible to say.

Nevertheless, the fascinating series of burials around Stonehenge illustrate that people were travelling huge distances to the monument over a period of perhaps a thousand years, suggesting that it possessed a Europe-wide reputation as one of the most sacred and revered places in the ancient world.