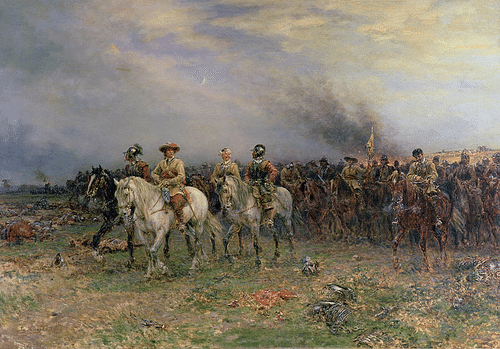

The Battle of Marston Moor near York on 2 July 1644 was one of the most important engagements of the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). The Parliamentarians won the battle which, involving over 45,000 men, was the largest of the First English Civil War (1642-1646). Instrumental in the victory and making his first starring appearance in the pages of history was one particular 'Roundhead' cavalry commander: Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658).

The Civil War So Far

King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) had clashed with Parliament, particularly over money and religious reforms for years, and, finally, a civil war broke out in 1642. The 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) met in over 600 battles and sieges over the duration of the conflict. London, the southeast, and the Royal Navy were in the Roundheads' hands while the king controlled the western and northern parts of England.

The first big battle of the war was the Battle of Edgehill in Warwickshire on 23 October 1642, which ended in a draw but prevented the king from marching on London. Smaller-scale battles followed, and there were numerous sieges and attacks on several major cities, notably the Royalist storming of Bristol in July 1643 and the successful defence of Gloucester by the Parliamentarians later in the same year. Another large battle was another draw, the First Battle of Newbury in September, also in 1643. A major boost to the Parliamentarians came next December when a military alliance was agreed with the Covenanters of Scotland, who swore to defend their Presbyterian Church, an institution that seemed seriously threatened if the Royalists won the war in England.

Meanwhile, Charles convened his own Parliament at Oxford, a small affair but with loyal members from the old London Parliament and a few new ones added. This was a declaration of his belief that he was the legitimate ruler and not the Parliament in London. The Oxford Parliament was able to raise funds for the king's army through taxes and duties. At the same time, hostilities ended in Ireland with the Catholic rebels there and so allowed, albeit briefly, the king's army to be supplemented by men at arms previously needed abroad. With the king consolidating his territorial control and the Parliamentarians benefitting from greater resources, the fractious conflict across England was still finely balanced.

The Parliamentarians got off to a good start in January 1644 when they won the Battle of Nantwich in Cheshire on the 25th. This was followed up by another victory at the Battle of Cheriton in Hampshire on 29 March. King Charles' plans for the year were dealt a serious blow by these defeats. The next big event was the Siege of York from April to July 1644, but there were serious happenings elsewhere in the kingdom, particularly at a small bridge in Cropredy, Oxfordshire, and then on the open expanse of Marston Moor in Yorkshire.

York to Marston Moor

Victory at Cropredy Bridge on 28 June allowed the king to secure Oxford and move to meet the Parliamentarians in the south. The Royalists also had the valuable boost of 11 cannons, which had been captured at Cropredy Bridge, but these events were far overshadowed by what was going on in the north of the country. First, there came the jubilant news that Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria, Charles' nephew and commander of the Royal cavalry, had brilliantly relieved York on 1 July. This vital northern city was safe, but the Parliamentarian armies that had besieged the city remained a serious threat to Rupert's army and/or the Royalist forces further south, depending on which direction they moved next.

The Parliamentarians had encircled York, but Rupert had, in, turn, encircled them, obliging the Roundheads to withdraw from their two-month siege of the city. Rupert then made the fateful decision the next day to attack the retreating enemy in an action typical of his bold approach to field warfare. Rupert was bolstered by the much-needed arrival of a force from York itself led by the Marquis of Newcastle. Consequently, the Prince commanded a total force of perhaps 18,000 men, of which around 6,000 were cavalry. The Marquis' army, though, only arrived on Marston Moor in the afternoon having spent the morning looting the camp of the Parliamentarians, who had left it earlier in the day to take up their own battle positions. Newcastle's northern army was known as the 'Whitecoats' because their coats were made from undyed material, their only decoration being an occasional cross. Rupert was displeased at the Marquis' tardiness and did not hesitate to say so: "My Lord, I wish you had come sooner with your forces. But I hope we shall have a victorious day" (Hunt, 127).

Facing the Royalists, there were, in fact, three large Parliamentarian armies totalling around 28,000 men: one led by the Earl of Manchester, another led by Sir Thomas Fairfax (aka Lord Fairfax, 1612-1671), and a third, a Scottish force of around 9,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry under the overall command of Alexander Leslie, Earl of Leven (d. 1661). Combined, the Parliamentarians far outnumbered the Royalists, but the advantage was mostly in infantry which was not crucial to the battle until its later stages.

Once they had realised the threat from Rupert, the three Parliamentarian armies turned around and faced him southwest of York on a stretch of relatively flat and open moorland between the villages of Long Marston and Tockwith. The battlefield did have a number of hedges and ditches to overcome, although some of the former were cleared in the early afternoon. The two sides faced each other across the moor, but little happened besides a few cannon shots being fired from either side in the mid-afternoon. The regiments of infantry in the centre, cavalry on either wings, and dragoons (hybrid infantry-cavalry) at the extremities of the lines, all shuffled impatiently like racehorses waiting for the off.

Major Lion Watson, a Parliamentarian scoutmaster gives the following account of those first few strange hours on the moor and explains why there was hesitancy on both sides to begin the fighting proper:

About two of the clock, the great ordnance of both sides began to play, but with small success to either; about five of the clock we had a general silence on both sides, each expecting we should begin the charge, there being a small ditch and a bank betwixt us and the Moor, through which we must pass if we would charge them upon the Moor, or they pass it, if they would charge us in the great corn field, and closes; so that it was a great disadvantage to him that would begin the charge, feeling the ditch must somewhat disturb their order, and the other would be ready in good ground and order, to charge them before they could recover it. (Hunt, 127)

Cromwell's Cavalry

Battle finally and, in the event, unexpectedly, commenced in the evening. The two Royalist armies, perhaps with Rupert and Newcastle not agreeing on how to proceed, had by then retired to their respective camps. At around 7 pm, the Parliamentarians saw the cooking fires of the enemy indicate they were likely saving themselves for the next day, and they took the decision to attack in force. A rainstorm no doubt added to the confusion in the Royalist camps, but they had maintained their defensive deployment and so were not completely overwhelmed at the first onslaught. The Parliamentary cavalry led by Sir David Leslie and Oliver Cromwell attacked the opposing cavalry's right wing who found themselves on broken ground. The Royalist cavalry was put in total disarray and roundly defeated; even Rupert lost his horse, and he was obliged to hide for a while in a bean field. The prince suffered the loss of his baggage train, and even his beloved hunting poodle 'Boye' was killed in the chaos. Cromwell did not escape unscathed, injured in the neck, he was obliged to leave the field while his wound was dressed.

Elsewhere on the battlefield, there was another clash of cavalry: Lord George Goring made significant headway against Lord Fairfax's cavalry on the right wing of the Parliamentarian army. However, at the heart of the battlefield, the Royalist infantry of pikemen and musketeers was by now being butchered by Cromwell's cavalry coming at them from the rear. One Parliamentarian, a captain, described the raging battle as "Hell's Gates" and that the infantry "made such a noise with shot and clamour of shouts that we lost our ears, and the smoke of powder was so thick that we saw no light, but what proceeded from the mouth of the guns" (Gaunt, 60). Cromwell, in an impressive piece of battlefield manoeuvring, then kept his cavalry together and drove them to assist that of Fairfax over on the right wing, where they had been caught in a crossfire of enemy musketeers.

Parliament's Victory

A part of Newcastle's northern infantry continued to fight, but they were almost totally wiped out (only 30 men survived), and what was left of the other two Royalist armies withdrew towards York. Even then, the Parliamentarians pursued them, as one eyewitness noted, "We had cleared the field of all enemies, and followed the chase of them…cutting them down so that their dead bodies lay three miles in length" (Gaunt, 62). By 9 pm, the bloody battle was over. A large portion of Charles' army in the field had been destroyed. Cromwell described the battle in a moving letter to his brother-in-law Valentine Walton which included news of his son's death:

[It was] an absolute victory…We never charged but we routed the enemy. The left wing, which I commanded, being our own horse, save a few Scots in our rear, beat all the Prince's horse. God made them as stubble to our swords, we charged their regiments of foot with our horse, routed all we charged…of 20,000 the Prince hath not 4,000 left…Sir, God hath taken away your eldest son by a cannon-shot. It brake his leg. We were necessitated to have it cut off, whereof he died…He was a gallant young man, exceeding gracious. God give you His comfort. (Hunt, 131-2)

The Parliamentarians had not only won the battle, killed some 4,500 Royalists, and taken 1,500 prisoners, they now had control of northern England with only a few isolated but, nevertheless, well-garrisoned castles still loyal to the king. Even York surrendered to Parliamentary forces on 16 July 1644.

Aftermath

The Battle of Marston Moor was a disaster for King Charles, but as the war had already shown, heavy defeats in the field did not necessarily mean the war was all over. The battle did have significant consequences for several of the key commanders. Cromwell, who had been steadily rising through the ranks, was able to demonstrate his abilities as lieutenant-general of Manchester's cavalry, and he would never look back. Similarly, Sir David Leslie's star had risen, and he gained much credit, too, for the victory. In contrast, Prince Rupert had blemished his reputation for earning dashing successes, and his decision to attack a larger retreating army was seen for the folly that it was. The Marquis of Newcastle fled in shame to the Netherlands, and his namesake city fell to the Parliamentarians shortly after.

The Second Battle of Newbury on 27 October 1644 brought only another indecisive result that ensured the English Civil Wars rolled on. It was not until after February 1645, which saw the formation of the professional New Model Army by the Parliamentarians, that just who would win this bloody conflict became more evident. The Model Army's victory at the Battle of Naseby in Northamptonshire in June was followed by more victories, including the siege of Bristol in 1645 and the capture of this vital port. The situation for King Charles, now effectively in exile in Scotland, had become utterly desperate.