Spanning across three continents and holding dominance over the Black and Mediterranean Seas, the Ottoman Sultanate (1299-1922) was a global military superpower between the 15th and 17th centuries. From the point of its inception in 1299, the Ottoman Empire expanded rapidly, mostly at the expense of European powers and rival Muslim states neighboring the Turks.

What started as a small principality or beylik in modern-day Anatolia, soon engulfed major swaths of Southern & Eastern Europe, Crimea, parts of the Middle East, major chunks of North Africa, and the Caucasus region in addition to important islands in the Mediterranean. Though the empire lost much of its territory following a costly defeat at the walls of Vienna in 1683, the military past of the Ottoman Turks is relevant even in the modern world, and their legacy is reflected flawlessly in the numerous monuments spread throughout what they once proudly declared as Osmanli Devleti (the Ottoman Empire).

Historical Background

The 11th century saw the rise of a Muslim Turkic tribe, hailing from the heartland of the Asian steppe, a land rife with brutal infighting and incessant struggle for domination. The Seljuk tribe swept over Persia and then began advancing westwards where they came into contact with the once-mighty Byzantine Empire (330-1453), a mere relic of its former glory but a formidable regional influencer nonetheless.

The Seljuk Sultanate (1037-1194) was the first major Muslim Turkic imperial power; in 1055, they claimed Baghdad, the metropolis of the Islamic caliphates, and hence held dominance over the decrepit and crippled Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258) whose rulers could now only entertain their minds with the stories of their golden past that had been long buried in the sands of time following the death of their great leader Harun al-Rashid (r. 786-809).

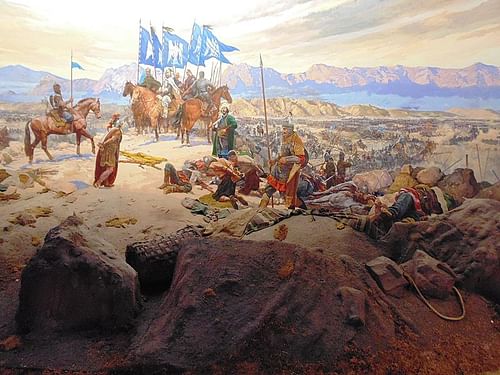

For the Turks, however, this was the first time that they became instrumental in establishing Islam’s dominance in uncharted territories, and their first victim was the ailing Byzantine realm. In 1071, the young and ambitious Sultan Alp Arsalan (r. 1063-1072) found himself facing a numerically superior Byzantine force but managed to secure an impressive victory at the Battle of Manzikert (modern-day Mazagirt).

This devastating defeat withered Byzantine control over Anatolia, and the Turks began flocking to these pasturelands; this was further catalyzed by the eruption of a massive threat in 13th-century Central Asia – the Mongols. Descendants of the Mongol leader Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227) soon reached Anatolia, which then played host to only a fraction of once-mighty Seljuk Kingdom, the Sultanate of Rum, which was easily shattered by Mongol warfare and became their vassal in 1243.

The aftermath left the several petty states spread throughout Anatolia, otherwise known as the Anatolian beyliks, more or less on their own, to quarrel among each other. But one chieftain, Osman Ghazi (r. c. 1299-1324), set upon fulfilling a grand ambition to build a state that would dwarf even the mightiest powers of its time; this was the beginning of the Ottoman Empire.

Consolidation of Anatolia

Osman I ruled over Bithynia, a beylik bordering the Byzantine lands to the west. He saw glory only in ġazā, a form of holy war directed at conquering non-Muslim lands, and had branded himself as a gazi (or ghazi). Using mostly guerrilla warfare, Osman began pushing into the Byzantine realm. Though his gains were only minor and he did not live to see the fulfillment of his biggest victory, the fall of Prusa (Bursa), Osman had set into motion the wheels of a Turkic juggernaut.

The 14th century saw more conquest in Asia Minor with Osman’s son Orhan Ghazi (r. 1323/34-1362) taking charge of his father’s realm and sweeping over Nicaea (Iznik) in 1331 and Nicomedia (Izmit) in 1357. The annexation of local Anatolian territories was done via both diplomacy and relentless Ottoman warfare. However, this unification and centralization did not appease some prominent tribes who wished to retain their regional autonomy and were by no means lacking the will and resources to do so.

The Karamanids, a rival Turkic tribe, sought the help of Timur (aka Tamerlane, r. 1370-1405), a prominent and ruthless Turko-Mongol leader, to halt the westward ambitions of Sultan Bayezid I (1389-1402). Bayezid, who had styled himself as Yilderim (meaning thunderbolt), and was the victor of the Battle of Nicopolis against a European coalition force in 1396, did not feel like bending the knee before Timur, and this invited Timur's wrath to Anatolia.

1402 saw the Battle of Ankara, the most disastrous defeat for the Ottomans within their heartland, Sultan Bayezid was captured by Timur’s forces and his empire tossed into the abyssal depths of tumult, chaos, and division. The Ottoman Interregnum (1402-1413) that followed was a decade-long civil war that wasted precious resources for infighting, but when Mehmed I (r. 1413-1421) emerged as the victor of the conflict, the Ottomans were on a track to become more powerful than ever before.

In the following years, the Ottoman borders were restored, and with the rise of Mehmed II (r. 1444-1446 & 1451-1481), the Empire of Trebizond and the Karamanids became subject states in 1461 and 1468, respectively. A rival eastern Turkic empire, the Ak-Koyunlu, briefly pressed against Anatolia but Mehmed checked their advance at the Battle of Otlukbeli (1473). The last vestiges of independent local rule in Anatolia (Ramazanids and Dulkadirs) existed only as a buffer between the Ottomans and their neighbors to the south: the Mamluk Sultanate.

In his bid for absolute dominance and to secure his realm from envelopment from his Shia Safavid rivals of Iran in the east and the Mamluks to the south, Sultan Selim I (r. 1512-1520), who had early on wrested control of eastern Anatolia from the Persians, annexed this buffer in 1516 before moving on with a sweeping conquest of the Mamluk territories. By the early 16th century, the Ottomans held complete dominance over Anatolia.

Conquests in Europe (Rumeli)

The Ottomans referred to their possessions across the Dardanelles as Rumeli. This province sprang up from the seeds sown in the time of Orhan Ghazi, whose troops raised the Ottoman standards in Gallipoli (1354) as part of his arrangement with the Byzantine emperor John VI Cantacuzenus (r. 1347-1354) who was facing a civil war in his realm. This collaboration born out of necessity soon fell apart, and the Ottomans and Byzantines found themselves at odds again. This, however, turned out to be better for the Turks who made swift advances in Rumeli, taking Adrianople (Edirne) c. 1362, followed by Thrace and southern Bulgaria (1363-1365), Sofia (1385), Nish (1386), and Salonica (1387).

These rapid advances did not go by unnoticed and the collective might of the European nobles and kings was soon set loose on the Ottomans in a series of military campaigns that some have loosely defined as crusades. However, these efforts were mostly foiled starting with an Ottoman victory at Kosovo (1389), following which much of Bulgaria, northern Greece, and Wallachia were annexed by 1395. Another major attempt at a collective assault against the Ottomans went bouncing off the target when Sultan Bayezid I incurred a serious blow to the European forces at Nicopolis (1396).

After the defeat at Ankara in 1402, which sparked the fuse of an intense civil war, the Ottomans were back on the European front where Serbia was engulfed in 1439. The Europeans once again mustered a collective force to face Sultan Murad II (1421-1444) who struck back with all his might and claimed victory at the Battle of Varna (1444). Interestingly, the battle was only won because of a fraction of the sultan’s force, a well-trained and professional standing corps known as the Janissaries, who stood their ground and fought off the enemy at a pivotal point.

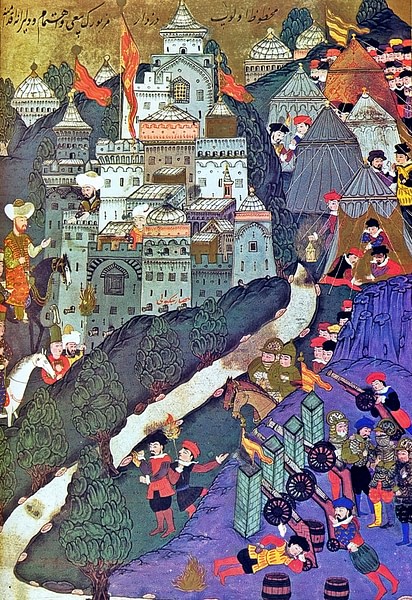

In 1451, when Sultan Mehmed II took over after his father's death, the only gap between the Ottoman realm to the East and the West was the amputated Byzantine Empire, confined to the legendary Theodosian Walls of what was once a capital exerting its authority over stretches of land spreading far and wide: Constantinople. Mehmed the Conqueror launched his offensive besieging the city for months until the final assault resulted in the fall of Constantinople: 1453. He entered the city as a victor and declared it as his empire’s new capital, which it remained until the last vestiges of Ottoman authority seeped away centuries later.

This is victory was only fuel to further ignite Mehmed’s imperialistic ambitions in Europe which manifested themselves in the absolute conquest of Serbia (1459) followed by the fall of Morea in Greece (1460), Bosnia (1463), and Otranto (1480) in Italy from where the sultan dreamed of sweeping over the country and claiming Rome. Italy was saved from this fate by the sultan's death, which was celebrated throughout Europe.

The greatest height of Ottoman ambition came with Suleiman I (r. 1520-1566), also known as Suleiman Magnificent, who struck from his European frontier with the conquest of Belgrade (1521), which opened up Hungary for conquest. The sultan returned soon enough to cash in on the opportunity with a massive force and secured a decisive victory against the young Hungarian King Louis II (r. 1516-1526) at the Battle of Mohács in 1526, following which he annexed large swaths of the fallen monarch’s realm – most of Hungary. Three years later, Suleiman launched another successful campaign through Hungary but had to turn back without a climactic victory from the walls of Vienna (1529).

In 1566, Suleiman the Magnificent, long past his youthful years, met his end outside the walls of Szigetvár, a strategically insignificant yet strongly defended Hungarian fort. With him, died the warrior spirit of the Ottoman sultans, only a few of whom would aspire to reach the same level of military skill and greatness as their predecessors. The fall of the Ottoman might was not swift, and further gains were indeed made in Europe, most notably Podolia, Ukraine in 1672.

Failing to modernize the military and establishing a stern control over the realm, the later Ottoman rulers were left behind in the race of imperial supremacy by their European foes. It was once again from the walls of the Austrian capital (Vienna) that the Turks had to retreat (1683), only this time battered and defeated, never to inspire the same level of fear and dread in the hearts of Europe.

Hegemony in the Black Sea Region & the Mediterranean

Crimea, then ruled by the Tatars (1441-1783), accepted Sultan Mehmed II as its suzerain in 1475, securing the Ottoman dominance in the Black Sea for three subsequent centuries. In the Mediterranean, the island of Rhodes, where the Knights Hospitaller had established their headquarters and from whence they raided pilgrim ships, surrendered to Suleiman the Magnificent in 1523, after courageously and daringly defending the city against insurmountable odds. However, the Ottomans failed to take over Malta (1565) where the Hospitallers had established their new headquarters.

The Ottoman army was lacking in one area when Mehmed II took charge: the navy. The young sultan took it upon himself to create a titanic fleet to fill the void, however, Mehmed’s fleet lacked larger vessels, which made them redundant in direct naval engagements. For instance, during the siege of Constantinople, a flotilla of four Genoese vessels, only three of which were military ships, broke through a huge Ottoman naval blockade of the city, bringing relief to the besieged Constantinople.

However, Suleiman the Magnificent was about to fill in the gaps in this section as well by commissioning new and improved vessels. He also appointed Hayreddin Barbarossa (l. 1478-1546), who was feared as a naval commander and had at one point been a rival to the Ottomans only to be cajoled into joining their ranks, as Grand Admiral in 1533. Barbarossa secured Ottoman supremacy in the seas against the Europeans and crowned his career with an impressive victory against a coalition naval force at Preveza (1538).

Suleiman’s son Selim II (r. 1566-1574) sent an expeditionary force to conquer Cyprus, which was accomplished by 1570, but it was followed by a naval disaster at the Battle of Lepanto (1571), which saw the destruction of the Ottoman fleet by a coalition armada called the Holy League. Though the Sultanate recovered from the immediate effects of this loss, their position was no longer unchallenged. The last addition to the empire’s borders in the Mediterranean region was Crete in 1669.

Ottoman-Persian Wars

The rivalry between the Sunni Ottomans and their Shia neighbors to the east, the Safavid Dynasty (1501-1736), started when the first Safavid ruler Shah Ismail (r. 1501-1524) declared Shia Islam as the state religion of his empire and openly declared hostility to neighboring powers, all Sunnis. Sultan Selim I asked their neighbors to invade, but Ismail fought off the incursions, following which he intruded in eastern Anatolia. In response, Selim I initiated the Ottoman-Persian Wars, which would span over three centuries and prove to be ultimately futile and exhaustive for both sides. To start, Selim massacred Safavid sympathizers in Anatolia following which he forced the Shah to face him at the Battle of Chaldiron (1514) where he pulverized the highly-experienced, although outnumbered, Persian field force with his gunpowder weapons and elite Janissary corps, forcing the Shah to flee the field in panic.

The Battle of Chaldiron was the first major military engagement against the Persians, although future battles would become more and more challenging. With his victory, Selim secured parts of Northern Iraq and Azerbaijan, and even went so far as to take the Safavid capital of Tabriz, but had to retreat due to tactical vulnerability and logistical issues. Selim’s son Sultan Suleiman continued the eastwards struggle of his father and took Tabriz and Baghdad in 1534, the latter being the former Abbasid capital, a symbolic addition to the Ottoman realm.

Hostilities were put aside temporarily with the treaty of Amasya in 1555, and for around three centuries thereafter, the relations between Ottomans and the Persians would see ceasefire agreements punctuated by violent confrontations. During this time, ambitious sultans made vehement attempts at reasserting military superiority against their rivals. Sultan Murad IV (r. 1623-1640), for example, launched an ambitious campaign and succeded in retaking Baghdad from the Safavids in 1639. The Ottoman-Persian wars raged on for two more centuries, but hostilities were buried for good with the treaties of Erzurum (1823 and 1847), which defined the borders between the two realms, and the two sides established diplomatic ties, the positive effects of which are seen even today.

Conquest of the Middle East & Gains in North Africa

After his campaign against Shia Iran in 1514, Selim had redirected his territorial expansion efforts, and the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt, Levant, and Hejaz, which had an inclination towards Safavid Iran and had hosted rebellious Ottoman princes as political leverage, was now a target.

Sweeping over the Ramazanids and the Dulkadirs in 1516, the last independent Anatolian beyliks which acted as buffers between the Ottomans and the Mamluks, Selim made it clear that he intended to push southwards. The two armies met at the Battle of Marj Dabiq (1516), north of Aleppo, where Selim destroyed the Mamluk field army using his gunpowder weapons. With the Mamluks utterly devastated on the field, their realm began to fold under the sway of the Ottomans; Syria, Levant, and Hejaz were quick to surrender.

By 1517, Selim had taken all of the Mamluk realm, Egypt included; compared to his victory against the Safavids, the 1516-1517 Ottoman-Mamluk conflict was a far bigger triumph. However, this incessant military struggle would ultimately take its toll on Selim himself who died in 1520, but not without having doubled the size of his empire in less than a decade. The sultan had also annexed Algiers in 1517; Tunis fell under the control of Suleiman in 1534, and this control was cemented through subsequent military expeditions.

Back in the Middle East, Selim II ordered the conquest of Yemen (1567-1570), following which the empire made gains in Tunis (1574) and in Fez, Morocco (1578).

Territorial Disintegration

In 1529, the titanic force of Suleiman the Magnificent placed Vienna under siege but failed to capture the city, despite having overwhelming numbers, owing in part to the challenges presented by the winter and lack of preparedness. Though Suleiman’s attempt at Vienna failed, his campaigns in Europe were remarkably successful, but over a century later, the Ottomans were no more ready for taking Vienna as they had been in 1529.

When they appeared once again before the walls of the Austrian capital in 1683 and were soundly defeated again. This was the turning point in the fate of the Ottoman Empire, marking the start of gradual territorial loss until nothing remained outside of what is modern-day Turkey, formed in the aftermath of the First World War (1914-1918) in 1922.