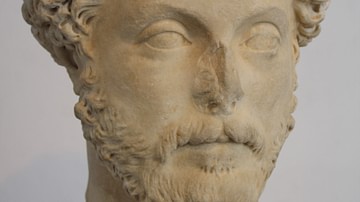

Plato's concept of the Philosopher-King (one who governs according to philosophical precepts and higher truths) is thought to be best exemplified through the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (r. 161-180 CE), the last of the Five Good Emperors of Rome and a devout student of Stoicism, whose principles informed both his life and reign.

Scholar Michael Grant describes Aurelius as “the noblest of all the men who, by sheer intelligence and force of character, have prized and achieved goodness for its own sake and not for any reward” (Grant, 139). This is the common view of Aurelius, whose reign was characterized by a devotion to his people and a stoic discipline expressed clearly in his work Meditations, a private journal he kept which, once published, has become his greatest legacy.

Aurelius was highly respected in his lifetime and is referred to as “the philosopher” by later ancient sources such as Cassius Dio (l. c. 155-235 CE) and the authors of the Historia Augusta (4th century CE), a history of Roman emperors. It is clear from both these sources that Aurelius' Meditations was known to them but the authors focus, not only on the written work – which Aurelius never intended for publication – but on how he lived his philosophy throughout his reign.

The Meditations is Aurelius' journal, written between c. 170-180 CE when he was on military campaigns in Germania, and expresses his philosophical, particularly Stoic, view of life. The work is a private reflection on how to live the best life possible – it is not a polished philosophical tract – and repeats a number of themes throughout its twelve books as Aurelius grapples with the same serious questions at different times. Scholar Gregory Hays elaborates:

The questions that the Meditations tries to answer are primarily metaphysical and ethical ones: Why are we here? How should we live our lives? How can we ensure that we do what is right? How can we protect ourselves against the stresses and pressures of daily life? How should we deal with pain and misfortune? How can we live with the knowledge that someday we will no longer exist? (xxiv-xxv)

His Meditations has inspired countless people through the centuries but, in the present day, he is probably best known for his depiction in popular Hollywood films such as Gladiator (2000). While his depiction in Gladiator is somewhat fictionalized, especially concerning his cause of death and his `vision' for Rome, that he should be played so sympathetically in the movie is a testament to his legacy.

Whatever artistic license the film may have taken with the facts of Aurelius' life, the spirit of the man comes through as a close proximation to Plato's concept of the Philosopher King articulated in Book V of the Republic. Plato writes:

Unless either philosophers become kings in their countries, or those who are now called kings and rulers come to be sufficiently inspired with a genuine desire for wisdom; unless, that is to say, political power and philosophy meet together…there can be no rest from troubles. (Republic V.473d)

Aurelius himself would never have thought to compare himself favorably with Plato's vision nor with the ideal of a Roman Emperor as embodied by his noble predecessor Antoninus Pius (r. 138-161 CE) who adopted him as successor. He saw himself as a student of philosophy, not as a “philosopher”, and as a man struggling to fulfill his obligations to the people who had faith in him, not as an “emperor”. It is precisely his humble view of himself which makes him the ideal candidate as the Philosopher King. Plato's concept stipulates that is precisely the man who loves wisdom more than power who is best suited to rule.

Antoninus Pius adopted and groomed Aurelius as a Roman emperor but it is clear that the young man would have preferred the life of the philosopher. In his Meditations he returns constantly to the theme of the importance of living a true, honest life in the attempt to find inner peace rather than pay attention to the trappings of power and the kind of responsibilities inherent in ruling an empire.

Youth & Introduction to Philosophy

Aurelius was born in Spain in 121 CE to an aristocratic Roman family which was politically connected. He was named after his father, Marcus Annius Verus, who had been named for his father and his father's father who were senators. His mother, Domitia Lucilla (l. c. 155-161 CE) was also a wealthy patrician and well-connected politically. At the age of three, following the death of his father in c. 124 CE, Aurelius was brought up primarily by his grandfathers and nurses.

When he was eleven years old he was introduced to philosophical thought by one of his teachers, Diognetus, and internalized the discipline which would guide him throughout the rest of his life. In his Meditations, Aurelius thanks Diognetus for the lessons he learned and lists them:

Not to waste time on nonsense. Not to be taken in by conjurors and hoodoo artists with their talk about incantations and exorcism and all the rest of it. Not to be obsessed with quail-fighting or other crazes like that. To hear unwelcome truths. To practice philosophy…to write dialogues as a student. To choose the Greek lifestyle – the camp-bed and the cloak. (I.6)

Aurelius' reference to the “camp-bed and the cloak” suggests the Cynic school of philosophy as the first to have a major impact on him. The Cynic School was founded by Antisthenes of Athens (l. c. 445-365 BCE), a student of Socrates (l. c. 469/470-399 BCE) and its teachings were later exemplified in the lives of Diogenes of Sinope (l. c. 404-323 BCE) and Crates of Thebes (l. c. 360-280 BCE). The Cynic philosophers, as well as Plato, would influence Zeno of Citium (l. c. 336-265 BCE) who founded the Stoic School of philosophy which would come to have a profound impact on Aurelius' life and thought later on.

The Cynic School was characterized by the discipline of self-denial which rejected luxuries, social status, and wealth along with unnecessary material objects. By freeing one's self on all non-essentials – including social conventions of polite manners and “proper” behavior – one would be free to pursue simply being one's self.

Aurelius seems to have found this kind of life appealing and pursued it by choosing the “Greek Style”, as he calls it, and sleeping on the ground or the floor of his room instead of his bed and adopting the simple woolen cloak of the philosopher. If he fully embraced Cynicism he would have also renounced any luxurious possessions, contented himself with the simplest food, and rejected basic hygiene as an expression of vanity. His immersion in this lifestyle, however, was curtailed by his mother fairly quickly who felt he should pursue goals more in keeping with the family name and their status in society.

His mother and grandfathers hired tutors to train the boy and no expense was spared. Historian Will Durant remarks, “never was a boy so persistently educated” and continues, “four grammarians, four rhetors, one jurist, and eight philosophers divided his soul among them…he was attached in boyhood to the service of temples and priests” (425). His early education also included the services of the highly-respected orators and rhetoricians Herodes Atticus (l. c. 101-177 CE) and Marcus Cornelius Fronto (d. late 160's CE) who would both exert significant influence over the boy. Aurelius and Fronto, in fact, would become life-long friends.

Adoption & Stoicism

In 138 CE, Antoninus adopted Aurelius and his future co-emperor Lucius Verus (r. 161-169 CE) as successors as stipulated by his predecessor Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE). Aurelius at this time took the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus and was betrothed to Antoninus' daughter Faustina. Antoninus then began a careful grooming of the young man as future emperor and this included not only responsibilities at court but further education by tutors.

Aurelius dutifully complied with his adopted father's wishes but found his new life unsatisfying. In his letters to Fronto (still extant) he complains about his boring lessons in law, his secretarial duties, and his life at court. He also expresses these feelings in one of his more famous lines from Meditations:

The things you think about determine the quality of your mind. Your soul takes on the color of your thoughts. Color it with a run of thoughts like these: Anywhere you can lead your life, you can lead a good one. Lives are led at court – so then good ones can be. (V.16)

Fronto had tried to dissuade his pupil from philosophical pursuits, feeling they were a waste of time, and directed him to what he saw as more practical disciplines. Aurelius had always been predisposed to philosophy, however, and his preoccupation with introspective thought on the meaning of any given action, and life in general, would continue throughout his life.

Fronto was disappointed, then, when he learned that, included in his former-pupil's education at court, he would be tutored in philosophy; but this news must have been a great relief to Aurelius himself. Antoninus hired two philosophers who would greatly impress Aurelius and whose teachings would inform the rest of the young man's life: Apollonius of Chalcedon (dates unknown) and Quintus Junius Rusticus (l. c. 100-170 CE), one of the greatest Stoic philosophers of his day.

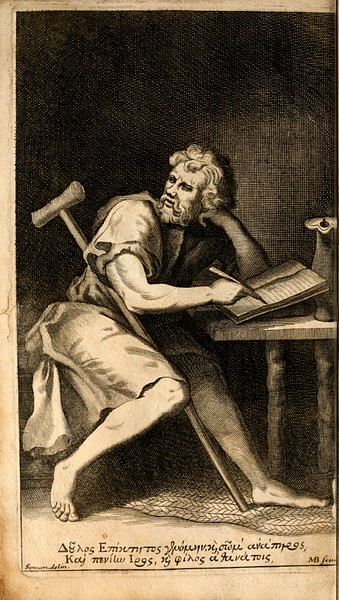

These tutors instructed him in Stoicism, the philosophical school first articulated by Zeno of Citium but fully expressed in the writings of Epictetus (l. c. 50-130 CE) in his Discourses and Enchiridion. Stoicism held that there was an eternal binding force to the universe called the logos from which all things came. The logos infused everything, bound it together, and allowed it to dissipate all in its own good time according to nature.

There was nothing in life, therefore, which could be called “bad” because all observable and unobservable events flowed naturally from the logos and judgments on whether an experience was “bad” or “good” were simply transient sense perceptions of the individual. A person could lead a peaceful, harmonious, life if that person focused on the nature of the logos and controlled one's sense-impressions. Epictetus writes:

It is not circumstances themselves that trouble people, but their judgments about those circumstances. For example, death is nothing terrible, for if it were, it would have appeared so to Socrates; but having the opinion the death is terrible, this is what is terrible. Therefore, whenever we are hindered or troubled or distressed, let us never blame others, but ourselves, that is, our own judgments. (Enchiridion I. 5)

In his Meditations, Aurelius thanks Apollonius and Rusticus for their instruction and notes that Rusticus introduced him to the work of Epictetus, lending him his own copy (Meditations, I.7). The Stoic view became Aurelius' view from this point on and he expresses this in another of the best-known passages from Meditations:

If it is good to you, O Universe, it is good to me. Your harmony is mine. Whatever time you choose is the right time. Not late, not early. What the turn of your seasons brings me falls like ripe fruit. All things are born from you, exist in you, return to you. (IV.23)

In 161 CE, Antoninus died and Aurelius became emperor. The senate preferred to ignore Hadrian's wish that Verus should co-rule with him as they thought him unfit for office. Aurelius, however, reminded them that Antoninus had promised his predecessor to adopt both himself and Verus as successors and refused to take on the mantle of power unless Verus was named co-emperor; the senate had no choice but to comply.

The Philosopher King

Verus was younger than Aurelius and far more interested in pursuing pleasure than the duties of an emperor. He threw lavish and expensive parties and gave luxuriant gifts to his guests. Aurelius, on the other hand, continued to live as he always had: simply and without pretension. He took his responsibilities seriously, even if he did not always care for them, and devoted all his energies to making sure his decisions were just. Cassius Dio writes:

The emperor, as often as he had leisure from war, would hold court; he used to allow abundant time to the speakers and entered into the preliminary inquiries and examinations at great length, so as to ensure strict justice by every possible means. In consequence, he would often be trying the same case for as much as eleven or twelve days, even though he sometimes held court at night. For he was industrious and applied himself diligently to all the duties of his office; and he neither said, wrote, nor did anything as if it were a minor matter but sometimes he would consume whole days over the minutest point, not thinking it right that the emperor should do anything hurriedly. For he believed that if he should slight even the smallest detail, this would bring reproach upon all his other actions. (Roman History, Book LXXII.6)

Shortly after coming to power, the province of Syria revolted and the Kingdom of Parthia invaded Armenia, which was under Rome's protection. When Cassius Dio notes how Aurelius performed his duties when “he had leisure from war” he is referencing very little time indeed; but Aurelius was pressed by other matters as well, both public and private.

Throughout the nineteen years of his reign, Aurelius would be constantly harassed by bloody military campaigns, natural disasters, and domestic sorrows. Of the five sons Faustina bore him, only one, Commodus (r. 177-192 CE) survived to adulthood. Aurelius had only been emperor about a year when the River Tiber flooded in 162 CE, destroying crops and livestock, resulting in widespread famine.

When Verus returned to Rome from his military campaigns against Parthia and the Syrian rebels, his troops brought the plague back with them. Verus, in fact, would die of the plague in 169 CE, leaving Aurelius to rule alone. At about this same time (c. 162-166 CE) there was a surge in Christian persecutions which have been blamed on Aurelius. Modern scholarship, however, claims that Aurelius never ordered any such edict and, in fact, tried to protect Christians from unjust practices such as higher taxation and confiscation of goods. Melito of Sardis (d. 180 CE), who addressed his Apology for Christianity to Aurelius, clearly refers to him as a protector, not a persecutor, in asking for his intervention.

The tribes of the Marcomanni and Quadi began invading the frontiers in c. 166 CE and Aurelius spent untold hours and resources trying to secure and maintain the boundaries as well as expand Rome's territory into the Danube region as a buffer. Although Plato promises an “end to troubles” once a philosopher becomes king, Aurelius had no end of troubles throughout his reign. Even so, as history and his own writings attest, Aurelius did his best to remain steady in the face of challenges, exhibiting what Hemingway would later call “grace under pressure” – the ability to remain steady and true to one's self no matter the circumstance.

Conclusion

The choices Aurelius made during his reign give evidence of a kind, compassionate, disciplined soul who placed a high value on loyalty to one's true self as well as to others. His insistence on honoring promises and upholding tradition, however, sometimes led him into error as seen when he refused to rule unless Hadrian's wishes were honored and Verus ruled with him. Verus proved a vastly inferior emperor to Aurelius in every respect.

His choice of Commodus as his co-ruler and successor in 177 CE, however, was his greatest mistake in that his son never shared his high ideals nor displayed his intelligence. That Commodus would essentially un-do all the good that Aurelius had done, handing over the rule of Rome to incompetents and amusing himself constantly in his seraglio (which allegedly was comprised of 300 girls and 300 boys) shows exactly how poor Aurelius' judgment could be. Aurelius seems to have sensed that his son would never measure up to the potential he saw in him and, when he died in 180 CE, Commodus would prove himself the worst choice possible as successor.

Yet it is this very `human-ness', this kindness and hope for others to share his same vision to become the best version of themselves which makes Aurelius so admirable and the Meditations so enduring. The work stands as a testament to the nobility of its author and endures because of the immense practicality and sense of the vision for life it expresses. There is no room for self-pity or self-excuse in the pages of Meditations; only the constant exhortation to do one's best under any circumstance and to use one's time wisely, for life is short. He writes:

You must one day realize at last of what cosmos you are a part and from what Governor of the cosmos your existence comes, and that a limit of time has been set aside for you, and if you do not use it to clear away the clouds from your mind it will be gone, and you will be gone, and it will never return again. (Book II.4)

Aurelius understood that, if one wants to change the world, one cannot live the way the rest of the world does. Even at the height of his power, he never betrayed his philosophical vision or his belief in a fundamental meaning to human life. He expresses this ideal in Meditations Book VIII.59: “People exist for the sake of one another; teach them, then, or bear with them.”

In this passage, as in many others, Aurelius pre-figures the much later ideals of the 20th century Existentialists who also held that the purpose of one's life is to be the very best human being one can be regardless of the circumstances or the actions of other people. At the same time, of course, he embodies the earlier concept of Plato's Philosopher King: the man who rules, not for himself, but for the greater good of his people.