The Urdubegis were a group of female warriors in the Mughal Empire, who protected the zenana, the harem of the emperor. Although the origins of female bodyguards go back to the beginning of Indian civilizations, the urdubegis were a Mughal creation. The only member of the urdubegis known by name is Bibi Fatima, who served in Humayun's and Akbar's court.

Origins

Starting from Chandragupta Maurya's court, we have two important texts that mention the need for female bodyguards. The first text comes from Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya (r. c. 321 to c. 297 BCE). He reports the presence of women who protected the Mauryan king, especially while he was out hunting. Women hunters accompanied the king, riding on chariots, horses, and elephants equipped with weapons. Although having male guards next to the king for his protection, was something very common in the Western world, the presence of their female counterparts was a bit of a surprise for Megasthenes.

The second text was the Arthashastra, written by Kautilya (l. c. 350-275 BCE), the advisor of Chandragupta Maurya. He wrote about the necessity of female guards due to the number of murders of previous kings. Kautilya describes the dangers of the harem:

When in the interior of the harem, the king shall see the queen only when her personal purity is vouchsafed by an old maidservant. He shall not touch any woman (unless he is apprised of her personal purity); for hidden in the queen's chamber, his own brother killed Bhadrasena; hiding himself under the bed of his mother, the son murdered king Karusa; mixed rice with poison, as though with honey, his own queen poisoned Kasiraja; with an anklet painted with poison, his own queen killed Vairantya; with a gem of her zone bedaubed with poison, his own queen killed Souvira; with a looking-glass painted with poison, his own queen killed Jalutha; and with a weapon hidden under her tuft of hair, his own queen slew Viduratha. (1.20, ed. Kangle)

Between 340 and 293 BCE, another group of female warriors was formed under the instruction of Kautilya. Known as the Visha Kanya (Poison Girls), these women were trained from childhood by being given small doses of poison, which would gradually help them build up a tolerance. Thus, these assassins would lure their prey by using their beauty and charm and then administer the kiss of death to the enemy of the King. According to a 9th-century Arabic text, the Secreta Secretorum, Aristotle (384-322 BCE) warned his student Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE) about the dangers of these "venomous virgins" before the young general set off on his Indian campaign. In another legend, the death of Alexander the Great was said to be the result of an embrace with a Visha Kanya, that may have been given to him as a trophy by King Porus, after his defeat.

The Visha Kanya were Indian, but other female bodyguards may have been brought from Central Asia, where the ancient Greeks believed the Amazons and other warlike women were located. Unfortunately, many sources are tantalizingly silent regarding the social background of these armed women. In ancient India, a king's retinue of women displayed his power, wealth, and status. Thus, female bodyguards seemed to serve two purposes: not only did they protect the king but also added to the king's stature in a theatrical display of divine power. While these warriors did exist, they did not have a specific title by which they were known, until the Mughal era.

The Mughals & the Harem

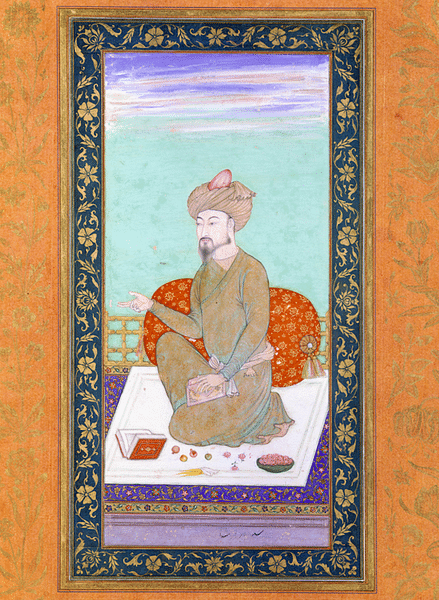

In June 1492, Babur, at the tender age of 12 inherited the province of Ferghana (a small but fertile province around modern-day Uzbekistan). Unfortunately, due to the political turmoil, he lost his throne, and so he traveled to Kabul, where he established his stronghold. Then in 1505, he journeyed to India for the first time, which would later lead to several other expeditions. Babur's harem had been a nomadic one that traveled with him during his exploits, thus, ensuring security was a must. Perhaps learning of the female bodyguards of the previous Indian kings, he established the urdubegis, a special group of women who did not practice the parda (meaning a veil), which allowed them to move around easily.

It was only under Akbar (r. 1556-1605) that the harem and the rules that would govern it until the end of the Mughal Dynasty were properly established. The book Magnificent Mughals (pg. 37-38) describes the layout of the zenana:

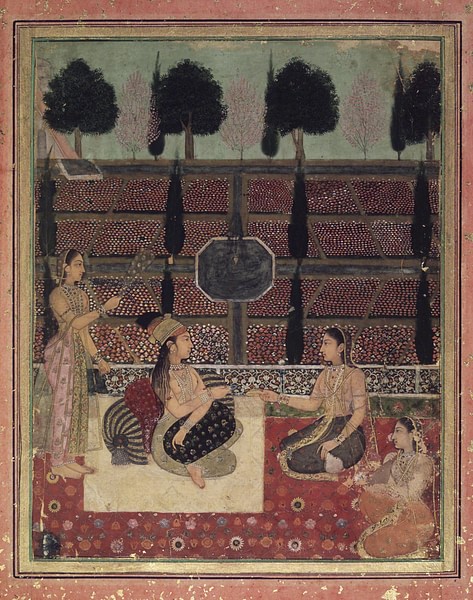

Life in the zanana was as diverse, complex, and multi-layered as that of a small city. Ordinarily, there were several thousand women housed in the various Mughal mahals, including mothers, grandmothers, wives, sisters, daughters, aunts, and other female relatives. In addition, the number of ‘service women' was very large, and included concubines, servants, slaves, female guards, spies, entertainers, soothsayers, and various visitors staying for indefinite lengths of time. By most accounts, life in the women's apartments was physically safe, financially secure, relatively stable politically, and replete with material luxuries, daily and seasonal entertainments, and the ups and downs of constant female companionship on a very large scale. (37-38)

While the concept of the Mughal zenana is far from the pleasure gardens that come to mind, entry into the harem was indeed restricted. Many women residing in the zenana practiced parda. Gull-i-Hina describes in her article how the Mughal women were expected to behave:

The public lives of women of nobility were governed by the laws of seclusion. The practice of parda, or the sequestering of women behind the veil or wall, had already been known in ancient and medieval India and had been used throughout history by many of the upper classes. By the time of the Mughals, seclusion was an accepted way of life for aristocratic families. (464)

Due to the increased number of inhabitants, there was a need for people to help maintain the smooth functioning of the zenana. Apart from the eunuchs, there were lady officials (who were married and often resided in their own homes away from the imperial harem) like the angas (foster-mother), the daroghas (matrons), mahaldars (superintendents), and the urdubegis (armed female guards).

The urdubegis were trained warriors and often belonged to tribes that did not practice parda, thus they would be visible to men on certain occasions. They were trained in the use of all weapons, like the use of bows and arrows, and spears, along with short daggers and swords.

Another mention of the urdubegis is found in the Travels in the Mogul Empire written by François Bernier, a French diplomat placed in the Mughal court. In his writings, he refers to Shah Jahan (r. 1628-1658) as Chah-Jehan and Princess Jahanara as Begum-Saheb. Within his travelogue, he mentions the war of succession where King Shah Jahan sends an invitation to his son, Aurangzeb, inviting him to the palace:

The cautious Prince likewise mistrusted Chah-Jehan; for he knew that Begum-Saheb quitted him neither night nor day; that she had dictated the message, and that there were collected in the fortress several large and robust Tartar women, such as are employed in the seraglio, for the purpose of falling upon him with arms in their hands, as soon as he entered the fortress. (61)

It is clear from the sources that the princes feared the urdubegis; their loyalty to the king made them a fierce force to be reckoned with. That is why, Aurangzeb did not carelessly wander into court, he was aware if he fell into the hands of the urdubegis, he would be unable to return alive.

Bibi Fatima

While Mughal emperors have left extensive records about their lives, there is rarely any mention of the urdubegis who protected the kings and their harem. The only name that appears in the records is that of Bibi Fatima, who was the chief armed woman during the reigns of Humayun (r. 1530-1540 and 1555-1556) and Akbar. Her service during the reign of Emperor Humayun was recorded in the Humayun-Nama, written by his half-sister Gulbadan Begum. The primary role of the urdubegis may have been to provide security but several mentions in the Humayun-Nama show that they may have been entrusted with other tasks as well. When Humayun wanted to send envoys to Haram, to propose marriage to one of her daughters, the two members selected for the task were Khwaja Jalal-ud-din Mahmūd and Bibi Fatima.

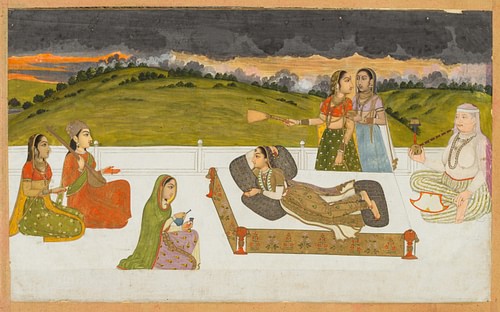

In 1546, when Humayun fell ill, there were only a few trusted people around him to take care of the young prince. As Princess Gulbadan writes: "He is said to have been insensible for four days. He was nursed by Māh-chūchak and Bibi Fatima, an armed woman (ordū-begi) of the haram (180)" Another aspect of Bibi Fatima's life that is mentioned in the book is the name of her daughter, Zuhra. Her years of service were rewarded by ensuring that her daughter would have a good marriage; it was proposed that she would be wed to the brother of Hamida, Humayun's wife. During the reign of Humayun's son, Emperor Akbar, Bibi Fatima is mentioned once again, but this time it's for a much sadder reason:

Now, in 1564, Bibi Fatima lamented to Akbar that Khwaja Mu'azzam had threatened to kill his wife Zuhra, who was her daughter. The emperor consequently sent the Khwaja word that he was coming to his house and followed the message closely. As he entered, the Khwaja stabbed Zuhra and then flung his knife, like a challenge, amongst the loyal followers. (65-66)

Despite this incident, it can be assumed that Bibi Fatima continued to serve under Akbar because there was no mention of her leaving.

There is general mention of the urdubegis, within the texts of Mughal biographies, but the only member of the urdubegis known by name is revealed in the Humayun-Nama, a book written by a woman. Perhaps, Gulbadan thought that the contributions of Bibi Fatima were worth mentioning, and her contribution deserved recognition by future generations.