Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604-1651) governed Japan as the third shogun of the Edo period. He implemented a number of important policies that not only consolidated his family's hold on power but also greatly impacted Japanese society for several centuries. These included formalizing the sankin kotai system that required daimyo to spend alternate years in Edo and their own territory and the exclusion edicts that restricted contact between Japan and foreign countries.

Early Years

Iemitsu was the eldest son of Tokugawa Hidetada, the second shogun of the Tokugawa clan, and the grandson of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate. Hidetada served as shogun from 1605 until 1623, at which time he abdicated in favor of Iemitsu. Up until his death in 1632, Hidetada continued to have a powerful influence over the government, so it is unclear which policies in this period originated with Hidetada and which with Iemitsu. After his father's death, Iemitsu quickly moved to consolidate his hold on power. One of his first actions was to accuse his younger brother Tadanaga of insanity, deprive him of his lands, and force him to commit seppuku. Judged by today's standards, this was a very brutal act, but at the time such behavior was commonplace. Iemitsu also engaged in various political maneuvers to make sure other branches of the Tokugawa family could not interfere in his government.

Consolidating Tokugawa Rule

Iemitsu was born in 1604 and, unlike his father and grandfather, had no firsthand experience of warfare. His great achievement, however, was to put in place a series of policies that consolidated his family's control over Japan. Through his victory in the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Ieyasu established the Tokugawa as the most powerful warrior family in Japan. In 1603, he established a 'warrior government', which in Japanese is called a bakufu (literally, a "tent government"). The Tokugawa controlled about 30 percent of the land in Japan, and the rest was in the hands of other warrior families called daimyo. The daimyo were divided between those who had been allies of the Tokugawa before the Battle of Sekigahara (fudai daimyo) and those who had only submitted afterwards (tozama daimyo). The land controlled by a daimyo family was called a han, and these varied greatly in size. The han of the fudai daimyo tended to be small and located in central Japan, whereas the holdings of the tozama daimyo were larger and located far from the political center. As former enemies of the Tokugawa, Ieyasu did not trust the tozama daimyo but he lacked either the desire or power to destroy them. In exchange for acknowledging the dominance of the Tokugawa at a national level, the daimyo were largely left to govern their own areas. While this acknowledgment may have been irksome for some of them, it was an arrangement that guaranteed the survival of their families.

During the period of civil wars in the 15th and 16th centuries, daimyo families were under constant threat from both internal division and external enemies. An able leader could expand a family's power base, but frequently, those gains would be lost due to the lack of a competent heir. Control over land and people could be attained in battle, but it could not simply be maintained that way. A successful leader required political as well as military skills. Even after their decisive victory in the Battle of Sekigahara, the Tokugawa also faced this danger. In the 1620s and '30s, Iemitsu overcame this threat by putting in place a series of policies that greatly strengthened the position of the Tokugawa and weakened that of rival daimyo families.

The System of Alternate Attendance

The most famous of these was the 'system of alternate attendance', which in Japanese is called sankin kotai. According to this system, daimyo had to spend alternate years in their own territories and in the city of Edo, the seat of the Tokugawa government. The wives and families of daimyo had to live permanently in Edo where they were, more or less, hostages. The practice of holding hostages in order to guarantee loyalty of allies and subordinates had a long tradition in Japan, but this system was formalized for tozama daimyo in 1635 and for fudai daimyo in 1642. This was just one of the measures included in a series of edicts called Laws of the Military Houses (Buke Sho-Hatto). The first of these had been issued by Ieyasu in 1615, but Iemitsu issued an expanded version in 1635.

The sankin kotai system continued to function up until the end of the Edo period in 1868, and its establishments had some far-reaching consequences that could not have been imagined by its creator. The system greatly hastened the development of Edo (modern Tokyo) as a city. Ieyasu had begun the construction of a huge castle in Edo in the early 1600s, and this work was continued by his successors. As part of the sankin kotai system, daimyo needed to construct residences in Edo. They built their mansions on land granted to them by the Tokugawa in the hilly area around the castle. This area was called yama no te (which means "hilly area") and stood in contrast to the low-lying area where ordinary people lived along the Sumida River which was called shitamachi ("downtown"). The population of Edo grew quickly because both the Tokugawa and the daimyo required many goods and services. By the end of the 17th century, Edo had a population of around one million and was the largest city in the world.

In order to facilitate the movement of daimyo from their home territories to Edo, it was necessary to create a good system of roads. In the early part of the 17th century, the government created a road network called the gokaido ("five roads"). This consisted of five major roads that radiated out from Edo, linking the city with other parts of Japan. The most important of these was the Tokaido that ran along the Pacific coast linking Edo with Kyoto. Post stations were built along these roads where travelers could find food, lodging, and entertainment. The government also set up checking stations to ensure that those using the roads had the required documentation and were not doing anything illegal. It was along these roads that the daimyo and their retainers moved in their trips back and forth to and from Edo. These so-called 'daimyo processions' could consist of hundreds of people. Local daimyo had to pay the cost of building and maintaining the roads. Many also built additional roads within their territories to facilitate movement.

Finally, the sankin kotai system stimulated economic growth. One of the main goals of the Tokugawa in forcing daimyo to come to Edo was to deplete their resources. Maintaining a residence in Edo and moving large numbers of retainers backwards and forwards required a great deal of money. By making the daimyo spend this money, the Tokugawa hoped to weaken them financially. For daimyo, there were two ways of increasing their income to meet this burden. One was to try and enlarge their share of the wealth generated from their territory by increasing taxes. This was not particularly effective as farmers had considerable capacity to resist this. The other approach was to try and expand the overall productivity of their land by stimulating economic growth. Conditions varied greatly from area to area, but many daimyo encouraged growth through the clearing of new land for agriculture, improved irrigation and farming methods, and the production of new products such as cotton, silk, salt, wax, and paper. Improvements in transportation also facilitated the development of local, regional, and national markets for these products.

In this way, the sankin kotai system, although originally intended simply as a means of political control, encouraged the growth of transport and trade, the expansion of towns and cities, and eventually a shared national culture as people and goods moved more freely around the country.

Restricting Contact with Foreign Countries

One other area where Iemitsu's policies had a lasting impact on Japanese society related to the edicts he issued restricting contact between Japan and foreign countries.

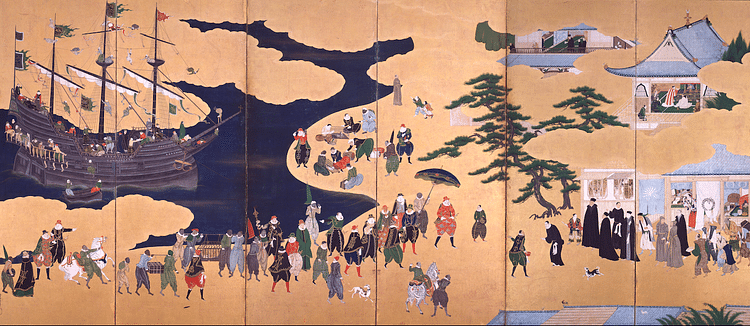

Relations with countries on the Asian mainland played an important role in the development of the Japanese cultural tradition from the earliest times. In the 16th century, however, new visitors from Europe arrived in Japan for the first time. These newcomers were keen to engage in trade and also to spread Christianity, a religion that had been unknown in Japan up until that time. Quite a lot of ordinary people converted to Christianity, as did a few daimyo. Christianity was not just a religion in a spiritual sense, as it was also closely associated with the imperial expansion of countries like Spain and Portugal. Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) and Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), the two warriors who began the process of national reunification at the end of the 16th century, were interested in European culture but suspicious of the new religion. Nobunaga in particular regarded some religious institutions as major obstacles to his attempts to reunify Japan.

Today Buddhism is thought of as being a peaceful religion, but in historical times, monks often found it necessary to physically defend their temples and monasteries. This was especially the case in the period of civil wars when warrior-monks engaged in battles with marauding daimyo armies. Enryakuji Temple located on Mount Hiei in northeastern Kyoto had an especially large army. In 1571, Nobunaga laid siege to the temple and destroyed it. It is said that hundreds, if not thousands, of monks were killed. In 1580 he also destroyed Ishiyama Honganji Temple (located on the site of the modern city of Osaka) after a ten-year war. Given these experiences, it is not surprising that both Nobunaga and Hideyoshi looked upon a religion like Christianity with suspicion.

Although he was keen to trade with Europeans, in 1615 Tokugawa Ieyasu banned Christian missionaries from coming to Japan. After Iemitsu became shogun, he prohibited Christianity altogether and engaged in widespread persecution. Many Christians were tortured before being killed.

In the late 1630s, a large rebellion broke out amongst farmers in Kyushu. It seems that the main causes were economic, but many of those involved were thought to be Christians. After brutally suppressing the rebellion, Iemitsu issued orders severely restricting contact between Japan and foreign countries. All Europeans were banned from coming to Japan except for the Dutch who were restricted to a trading post called Dejima on an island in Nagasaki harbor. Japanese who were already overseas – and there were many of these, engaged in trade in various countries in South-East Asia – were prohibited from returning home. In Japanese, these restrictions on foreign contact are called sakoku, which means "national isolation". Historians used to stress the negative impact these policies had on Japan, but more recent research has emphasized the fact that Japan was not totally isolated. In addition to contact with Dutch Nagasaki, Japan also maintained relations with China and Korea as well as the inhabitants of the Ryukyu Islands (modern-day Okinawa Prefecture) and the Ainu people in what is now Hokkaido Prefecture but which, at that time, was outside of Japanese control.

The motivation for Iemitsu's restrictions on contact with foreign countries is not completely clear. However, it seems most likely that he believed rival daimyo families might seek foreign support in rebelling against the Tokugawa. In this regard, the policy of alternate attendance and national isolation can be seen as having the same goal: the preservation of Tokugawa rule. From that perspective, both these policies were successful as the Tokugawa managed to stay in power until 1868.