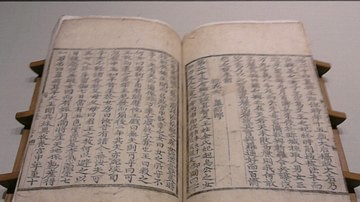

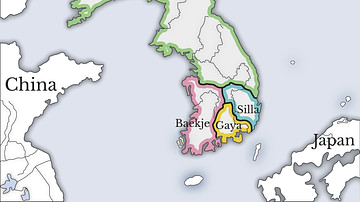

The Samguk sagi ('History of the Three Kingdoms' or 'Historical Records of the Three States') is a 12th-century CE text written by Gim Busik which is considered the first history of Korea. The text covers the history of Silla, Baekje (Paekche), and Goguryeo (Koguryo), the Three Kingdoms which dominated the Korean peninsula between the 1st century BCE and 7th century CE. Although the work is a history book, the primary motivation for its compilation was the long-held East Asian view that history can help guide the present and offer valuable practical lessons on good government and moral conduct.

Authorship

The Samguk sagi is thought to have been commissioned by King Injong of Goryeo (1122-1146 CE), the kingdom which ruled Korea from 918 to 1392 CE. The man given the task of compiling Korea's first official history was Gim Busik (1075-1151 CE), a Confucian scholar and court official of Silla descent – all points which are evident in Kim's selection of material and commentaries. Gim had already gained fame when he successfully led a Goryeo army to quash the Myocheong rebellion of 1135-36 CE. Gim and his ten assistants set about gathering older sources and although specific citations are rare, the bibliography of the Samguk sagi lists 69 Korean and 123 Chinese works consulted. The most important of these was the now lost Ku samguk sa ('Old Three Kingdoms History'). Gim modelled his presentation on what became the classic history textbook of the time, the Shiji by Sima Qian (c. 145-86 BCE), China's first historian. Gim's final version was completed and presented to the Goryeo court in 1145 CE.

Subject Matter

Imitating the jizhuan (Korean: kijon) approach of Sima Qian, the Samguk sagi begins with a chronological year-by-year presentation of each of the three kingdoms – Silla, Goguryeo, and Baekje – from their founding to their collapse and the beginning of the Goryeo state. Silla has twelve chapters devoted to its history, Goguryeo ten, and Baekje six. The state of Barhae (Parhae), which governed a part of northern Korea and Manchuria from the 7th to 10th century CE, is not covered. These history sections are known as benji in Chinese and pongi in Korean. Next, there are three chapters of chronological reference tables (yonpyo) and then a number of essays (zhi in Chinese, chi in Korean) spread over nine chapters and dealing with different aspects of Korean culture such as religious ceremonies, local geography, law, economics, astronomy, traditional clothing, and music. The book concludes with ten chapters containing 52 main and 34 secondary biographies of people instrumental in the history of Korea (liezhuan in Chinese or yolchon in Korean). The figures covered include artists, scholars, political rebels, virtuous women, generals, and statesmen. The biography of the general Kim Yu-sin is typical and weaves a historical narrative of his great deeds with myths and hearsay of his birth and miraculous explanations of his victories on the battlefield.

Whilst some attempt was made to present the facts only, the Samguk sagi does reflect the Confucian view of the world which was prevalent at that time in the Goryeo kingdom, both in presentation and in the choice of texts and topics included. It also contains many points of commentary by Kim, as was traditional, to highlight what he perceived as praiseworthy actions and those he considered as failings.

Besides history, the Samguk sagi contains many myths and legends. One of the most famous is the story of Prince Hodong. The handsome prince of Goguryeo was one day offered the daughter of the Chinese governor of Nangnang but he declined unless she proved herself worthy. The governor had a mysterious drum and horn instrument which sounded whenever an enemy approached and Prince Hodong insisted the girl first destroy this, which she did. The wily prince then attacked Nangnang unannounced. The capital fell and the governor killed his daughter in revenge before surrendering himself to the prince. Hodong did later get his comeuppance, though, when he was falsely accused by his jealous step-mother of making improper advances. Rather than displease his father with an embarrassing episode, Hodong nobly committed suicide. The story and many other such tales were designed to illustrate proper and improper behaviour and chivalry.

Legacy

The Samguk sagi had a sequel of sorts, the Samguk yusa ('Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms') which was completed in 1285 CE by the Buddhist scholar-monk Iryeon. The text covers the history and legends of Korea's founding right up to the 10th century CE and offers more on mythology and Buddhist culture than its predecessor.

In addition, as the Samguk sagi draws on hundreds of earlier sources it has become an invaluable reference work since many of these ancient texts have since been lost, including all 69 Korean texts referred to in the bibliography. Further, the book is itself a useful source for linguists studying the history of transliterated Chinese words, especially place names.

Perhaps its greatest contribution, though, is the effect the Samguk sagi has had on the very idea of what was ancient Korea and sowing the first seeds of Korean nationalism. By emphasising the role of the southern kingdom of Silla, representing Goryeo as its natural cultural successor, minimising the role of the northern Goguryeo kingdom, and ignoring the (also northern) contemporary state of Balhae, the picture given is of a Korean state politically and culturally unique and fully independent from its powerful northern neighbour China.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.