Richard, 3rd Duke of York (l. 1411-1460 CE) was the richest man in England and one of the nobles who sparked off the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487 CE), a dynastic dispute that rumbled on for four decades between several English kings, queens, and barons. Richard, leader of the Yorkists who set themselves against their rivals the Lancastrians, became Protector of the Realm under Henry VI of England (r. 1422-1461 CE & 1470-1471 CE) when that king suffered from episodes of insanity. Perhaps initially Richard only wished to better his great rival the Earl of Somerset (d. 1455 CE) but he made a bid for the crown itself and was defeated by an army led by Henry's wife, Queen Margaret (d. 1482 CE). Killed in the battle of Wakefield in December 1460 CE, the pretender's head was displayed on a pike in York. The Wars of the Roses then continued as two of Richard's sons bettered their father and each became king: Edward IV of England (r. 1461-1470 CE & 1471-1483 CE) and Richard III of England (r. 1483-1485 CE).

Family & Early Life

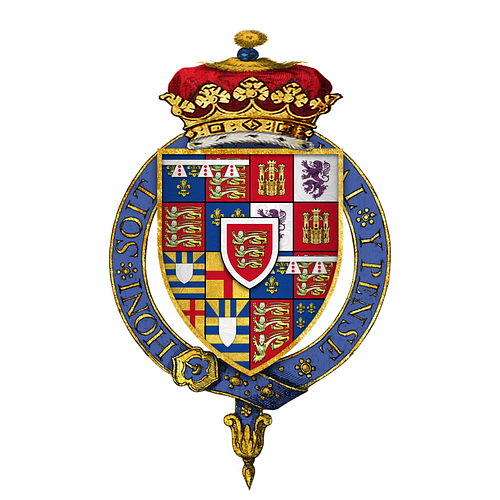

Richard was born into a noble family on 22 September 1411 CE, the only son of Richard, Earl of Cambridge (d. 1415 CE) and Anne Mortimer, the daughter of the Earl of March (1388-1411 CE). Richard had some royal blood in his veins as he was the great-grandson of Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377 CE) via that king's son Lionel, Duke of Clarence (d. 1368 CE). This meant Richard was the cousin of Henry VI, who was descended from Edward III's son John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (d. 1399 CE). As Lionel was older than John, it meant that Richard actually had a stronger claim to the throne than Henry had. Richard was, too, the nephew of Edmund Mortimer who himself had claimed he was the legitimate heir to Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE).

In 1415 CE Richard's father was executed by Henry V of England (r. 1413-1422 CE) on charges of treason. Henry V was of the house of Lancaster so one might think that Richard, of the house of York, already had a keen motive to bring about the fall of the Lancastrians. The standard view of historians, though, is that despite this and Richard's own royal credentials, it was not until Richard was exiled in 1459 CE that he really sought to overthrow his king, Henry VI. Before that, Richard was much more concerned, at least publicly, with being seen as a figure of reform and the man who could rid the government of corrupt and incompetent officials. He wished to remove rivals, certainly, and possibly have himself chosen as Henry's heir, but not to replace the king while he lived. Richard's supporters would not have allowed such an act. This is to jump ahead in the story, though. At present, suffice to say that Richard was a young nobleman with royal blood and powerful family connections. And like all powerful nobles, he had ambitions.

When Richard's uncle, Edward Plantagenet, died at the Battle of Agincourt in France in 1415 CE, he inherited his title and became the 3rd Duke of York and owner of its associated estates. In 1425 CE Richard inherited another uncle's estates and so, still only 14, he became one of the richest men in England. By 1436 CE, tax records show that the duke was at the very top of the kingdom's rich list with an income of £3,230, a figure 50 times greater than the lowest-ranked peer. Richard then loyally served Henry VI in France, where he funded his army himself in 1436-37 and 1440-45 CE, and he rose to become the king's lieutenant there, that is the commander of the army. He repeated the role in Ireland in 1447 CE, although that position, frustratingly, excluded Richard from the royal court.

Although the duke was powerful and had many allies, he could easily make enemies, too. The historian R. Turvey gives the following assessment of Richard's character:

York was his own worst enemy in that he was too arrogant, stubborn and demanding. Instead of exercising patience and cultivating friendships, he preferred confrontation and challenge. He had little time or respect for those whom he considered his inferiors in title, intellect and military skill. (65)

Richard married Cecily Neville (1415-1495 CE), the daughter of the Earl of Westmorland, c. 1429 CE. The couple would have seven children, the eldest being Edward, born in April 1442 CE in Rouen in France. The fourth son was Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who was born on 2 October 1452 CE. Both of these sons and Richard's grandson Edward would all one day become kings. Richard's other children with Cecily were Edmund, George, Duke of Clarence, and three daughters: Anne, Elizabeth, and Margaret.

The Demise of Henry VI

Henry VI of England had a troubled reign. Coming to the throne as a minor following the early death of his father Henry V, the young king was manipulated by ambitious barons, and his malleable and easy-to-please character only made things worse. Henry's aversion to warfare proved unpopular and his choice of associates even more so, especially William de la Pole, the Duke of Suffolk. Henry's wife, Margaret of Anjou (m. 1445 CE), niece of Charles VII of France (r. 1422-1461 CE), was also seen as a dubious addition to the royal court. There were, too, allegations of corruption at court, a lack of good government at a local level, and upset over Henry's intervention in disputes between various nobles. There was even a rebellion by commoners and local dignitaries led by the former soldier Jack Cade in 1450 CE which called for the removal of certain corrupt and inept court officials, a reduction in taxes, and a return to law and order in the southeast. Another desire of the rebels was to see Richard, Duke of York, given a more prominent role in the king's council of advisors who were seen, at present, as grasping and incompetent. As Jack Cade wrote in the document he sought to present to the king, The Complaint of the Poor Commons of Kent:

The king should have as his advisers men of high rank from his royal realm, that is to say, the high and mighty prince, the Duke of York, exiled from the service of the King by the suggestions of that traitor the Duke of Suffolk.

(quoted in Turvey, 74)

The message was that Henry was neglecting the necessities of everyday government and being manipulated by 'evil councillors'. Even if the rebellion fizzled out after causing much destruction in London, a call for change was in the air and Richard, although not in any way involved in Cade's movement, came to represent the hopes of those who wanted Henry ousted and to settle old scores with their rivals. One such family which supported Richard was the Nevilles of Middleham who sought allies in their own struggles with the Percy family. Such families as these were the product of what historians have called 'bastard feudalism' where rich landowners were able to possess private armies of retainers, accumulate wealth, and diminish the power of the Crown at a local level.

Then an unexpected crisis came. The Hundred Years' War (1337-1453 CE) with France was ultimately lost and with it all England's territory in France except Calais. It had all been an expensive waste of effort. In 1453 CE, the king suffered his first episode of insanity, a problem he may have inherited from his maternal grandfather Charles VI of France (r. 1422-1461 CE). As a consequence of the king's incapacity, Richard, the Duke of York, as the senior member of the royal dynasty, was made Protector of the Realm, in effect, regent, in March 1454 CE.

Rivalry with the Earl of Somerset

Richard might have been the most powerful man in England but he still wanted more, and he tried to persuade the king to nominate him as the official heir to the throne (this was before Henry had a son of his own). And if Henry was unwilling, there was always the possibility of using force. Ever since 1399 CE when Henry Bolingbroke had usurped the throne, made himself Henry IV of England (r. 1399-1413 CE) and murdered his predecessor Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE), the precedent had been set that one could become king by victories on the battlefield.

Richard did have a serious rival for the throne, besides the king presently sitting on it, and that was Edmund Beaufort, Earl of Somerset who was also a descendant of Edward III but through that king's son John of Gaunt, father of Henry IV of England, first ruler of the House of Lancaster. The Duke of York and the Earl of Somerset were soon at odds as each tried to get themselves nominated as Henry's heir, and this was the start of what later became known as the Wars of the Roses when England's nobility wrestled for the crown, splitting into two major groups, the Lancastrians and the Yorkists. Richard and Somerset, besides being political rivals, also hated each other, Richard particularly despised Somerset's capitulations in France at the end of the Hundred Years' War when Somerset replaced Richard as the commander of the king's army. In addition, the Duke of York was no doubt greatly frustrated at seeing King Henry still give Somerset favour, even after the failures in France, when they both returned to England. Finally, the king's debt to Richard of some £38,000 (well over $20 million today) for the upkeep of his army was another bone of contention.

In February-March 1452 CE Richard had even formed an army from his Welsh lands and marched to face Somerset, the so-called Dartford coup d'etat, but then backed down when he realised he had no support amongst the king's council. Richard had even had to publicly swear his loyalty to the Crown in St. Paul's Cathedral. Now, in 1454 CE and in a stronger position in terms of allies (but in other ways weaker because of the birth of Henry's son, Edward, in 1453 CE), Richard prepared to make a second bid for power. In 1455 CE the Duke of York imprisoned the Earl of Somerset in the Tower of London. The Lord Protector also reduced the expenditure of the royal household and restored law and order in the troublesome north of England. However, once more the Fates intervened when a somewhat-recovered king Henry dismissed his regent Richard and released Somerset form the Tower. Both men, Richard and Somerset, were now intent on all-out warfare to settle their differences.

In March 1455 CE, a call for Parliament did not invite Richard to participate. As a consequence, the duke marched south and met Somerset and a small force of the king's at the Battle of St. Albans, Hertfordshire, on 22 May 1455 CE. The whole affair was a mere skirmish, but it was the first battle of the Wars of the Roses. During the St. Albans fighting, Somerset was killed and Henry was himself slightly injured in the neck, forced to hide with a local tanner. Richard found the king and, illustrating that he was perhaps not yet intent on regicide, escorted him to safety.

Exile

Richard, realising the king could easily be manipulated - Henry had even forgiven him for the 'trouble' at St. Albans - then swore loyalty to Henry. Richard was made the Constable of England in 1455 CE and assumed the role of the king's principal adviser. In November 1455 CE Richard was made the Protector of the Realm for a second time as Henry's health declined again. However, this time the duke only kept his job for three months as Queen Margaret now took a greater role in her husband's government.

Henry, recovered again, managed, on 25 March 1458 CE to reconcile the Yorkists and Lancastrians in what became known as 'Loveday', obliging them to walk hand-in-hand in a procession in London. As part of the peace, the Yorkists were made to promise they would give compensation to those who suffered at the Battle of St. Albans.

However, the peace did not last long and, despite a Yorkist victory at Blore Heath on 23 September 1459 CE, Richard still faced a formidable obstacle to his ambitions in the form of Queen Margaret, now with an heir to defend. Margaret hated Richard so intensely she even led an army against the duke, defeating him at his headquarters in Ludlow at the Battle of Ludford Bridge on 12 October 1459 CE. The Duke of York fled to Ireland while Parliament, the November 1459 CE 'Parliament of Devils', identified him as a traitor, passed the death sentence on him and disinherited his heirs. It seemed now that the only way forward for Richard was to take the throne itself.

Bid for the Crown

In 1460 CE a Yorkist army led by Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick (1428-71 CE) and Richard's son Edward, Earl of March, defeated Queen Margaret's army at Northampton on 10 July and then captured King Henry. Richard could now return from Ireland, and he persuaded Henry, who was now in the Tower of London, to name him as the official heir to the throne and disinherit his own son Prince Edward, a decision ratified by the Act of Accord of 24 October 1460 CE. Richard had even marched into Parliament and publicly declared his belief he was the rightful heir, but that institution would not depose Henry. Richard would either have to wait for Henry's death or push his cause via the battlefield alone.

However, at the Battle of Wakefield in Yorkshire on 30 December 1460 CE the Yorkist cause suffered a disaster. The Duke of York was killed and his army was defeated by a much larger force of Henry VI loyalists led, once again, by the queen. Quite why the duke and his smaller army left the safety of Sandal Castle to be cut down by the enemy is not known, but treachery is the most likely answer, perhaps even an empty promise by the pro-Lancastrian Sir Andrew Trollope that he would defect to the Yorkist side if they came out and fought. Margaret ensured that Richard's head was displayed on a pike at Micklegate in York, adding a paper crown to remind everyone he had been a mere usurper. The remains of the man who would be king were interred at Pontefract and then later moved to Fotheringhay, the burial place of the House of York.

The Wars of the Roses were not over yet, though, and would not be for a few more decades. Edward, the Duke of York's son, backed by the Earl of Warwick, was promoted as a replacement to his father and to King Henry. When Edward won the bloody Battle of Towton in March 1461 CE, the largest and longest battle in English history, this is indeed what transpired. Henry VI was deposed, and he, Queen Margaret, and their son Edward all fled towards Scotland. Edward of York, just 19 years of age, was crowned Edward IV at Westminster Abbey on 28 June 1461 CE. Edward would be succeeded in 1483 CE by his brother Richard III who would eventually lose the Wars of the Roses to the Lancastrian Henry Tudor, aka King Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509 CE).

Richard, Duke of York was an important figure in history, but his name, and failed ambition, lives on in other ways, notably in the mnemonic device learned by schoolchildren (including this author) to help remember the order of the colours of the rainbow:

Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain

Red - Orange - Yellow - Green - Blue - Indigo - Violet.