The Battle of Agincourt on 25 October 1415 saw Henry V of England (r. 1413-1422) defeat an overwhelmingly larger French army during the Hundred Year's War (1337-1453). The English won thanks to the superior longbow, field position, and discipline. The French suffered from a reliance on heavy cavalry in poor terrain and the ill-discipline of their commanders.

The consequences of the battle included Henry being able to more easily take control of Normandy and then march on Paris. Further, under the 1420 the Treaty of Troyes, Henry V achieved his purpose and was nominated both regent and heir to the French king Charles VI (r. 1380-1422). Thanks to his victories and with a little literary help from such figures as William Shakespeare (1564-1616), Henry V has become an enduring national hero and Agincourt remains one of the most celebrated battles in English history, commemorated in art, literature, and song.

The Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War between England and France had begun with Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377) striving to back his claim to the French throne by force. Edward's mother Isabella had been the daughter of Philip IV of France (r. 1285-1314) but birth and diplomacy would not be enough to persuade the French kings to hand over their throne. The English did get off to a flier when the war finally broke out, first destroying a French fleet at Sluys in the Low Countries in 1340 and following this up with two great victories on the battlefield: Crécy in 1346 and Poitiers in 1356. Both saw the devastating English longbow overcome a hefty French numerical advantage. At Poitiers, Edward III's son, Edward the Black Prince (1330-1376) managed to capture King John II of France (r. 1350-1364) which led to the 1360 Treaty of Brétigny which saw Edward III give up his claim to the French throne but recognised him as the new overlord of 25% of France.

After a period of peace from 1360, the Hundred Years' War carried on as Charles V of France, aka Charles the Wise (r. 1364-1380) proved much more capable than his predecessors and he began to claw back the English territorial gains. Charles astutely avoided large scale battles, which, in any case, the English could no longer afford to indulge in, and by 1375, the only lands left in France belonging to the English Crown were Calais and a thin slice of Gascony. During the reign of Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399) there was largely peace between the two nations, but when Henry V took the throne in 1413, the war was very much back on again.

The Ambition of Henry V

With French pirates running riot in the English Channel and the chance of lands and booty in the event of an invasion of a teetering France, the majority of English barons and Parliament were enthusiastic for action. Henry V also had the financial backing of the church after he had dealt with the Lollard heresy in 1414. The English king had another advantage - the descent of Charles VI of France into madness resulted in the French nobility squabbling amongst themselves and so dividing the country into chaotic factions, principally the Burgundians and Armagnacs. The time was ripe for Henry to press his claim to be the rightful king of France and, significantly, the royal arms still showed the three lions of England and the fleur-de-lis of France. It was now time to make the claim a reality.

Henry showed his clear intent when, in mid-August, he invaded Normandy with an army of around 10,000 men provided by just about all the barons of a remarkably single-minded England. Henry led his army in person and was aided by his two brothers the Dukes of Clarence and Gloucester. The English captured the port of Harfleur after a grueling five-week siege. With winter around the corner and his force already depleted to 6,000-7,000 men by the longer-than-expected fighting at Harfleur and a devastating wave of dysentery, Henry decided to withdraw to English-held Calais and regroup. The king left Harfleur on 8 October 1415 and made his way along the coast until he was obliged to lead his army far inland in order to cross the Somme river. The French had destroyed bridges, heavily guarded others, and scorched the countryside to deny the invaders vital supplies. Henry finally found a shallow crossing point near Voyennes on 19 October. It was on the way back to the northern coast that a large French army intercepted the invaders, by then, somewhat ironically, on their way home.

Troops & Weapons

Both sides at Agincourt had heavy cavalry of medieval knights and infantry but it would be the English longbow that once again proved decisive - still the most devastating weapon on the medieval battlefield. These longbows measured some 1.5-1.8 metres (5-6 ft.) in length and were made most commonly from yew and strung with hemp. The arrows, capable of piercing armour, were about 83 cm (33 in) long and made of ash and oak to give them greater weight. A skilled archer could fire arrows at the rate of 15 a minute or one every four seconds. The French did have a small contingent of archers but continued to favour crossbowmen, who required far less training than archers but who could only fire at a rate of one bolt to five arrows. English archers were usually positioned on the flanks from where they could more easily hit the enemy horses which typically only had armour protection on their heads and chests.

In terms of cavalry at Agincourt, the better-equipped men-at-arms (who could be of knightly rank or not) wore plate armour or stiffened cloth or leather reinforced with metal strips. Their favoured weapons were the lance, sword and poleaxe. Men-at-arms could begin fighting on horseback and then dismount or start off on foot from the very beginning. Ordinary infantry, usually kept in reserve until the cavalry or dismounted knights had clashed, had little armour if any and wielded such weapons as pikes, lances, axes, and modified agricultural tools. There were few cannons used at Agincourt, still then a relatively new and unreliable weapon. The English had none (even if they had used them in the siege of Harfleur) while the French likely had only a few small handheld ones.

In terms of ratio, there was a much higher proportion of archers in the English army at Agincourt compared to the battles at Crécy and Poitiers, at least 3:1, archers to men-at-arms. Notable archer companies, numbering around 500 each, came from Lancashire, Cheshire, and Wales. At Agincourt, the vital archers were commanded by the greatly experienced Sir Thomas Erpingham (b. 1357). It should also be noted that Henry's high ratio of archers was not just down to weapons choice. An archer's daily wage was only half that of a man-at-arms, and Henry only had cash for a few months of fighting in the field; the king hoped that booty would supply the shortfall and enable him to prolong his campaign.

Battle

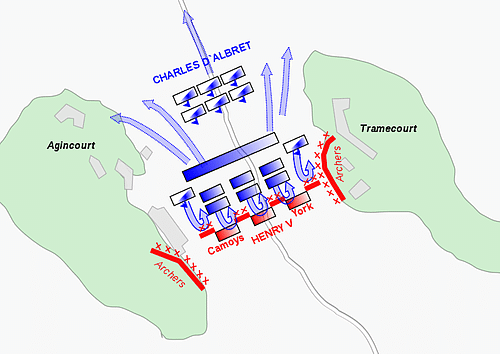

Henry was still only 28 but he had already established himself as a fine military leader in battles against English and Welsh rebels in the first decade of the 1400s during the reign of his father Henry IV of England (r. 1399-1413). The king was now ready for his ultimate test but the French had not been idle since Henry had landed in Normandy. The Constable of France, Charles d'Albret, assembled an army of around 20,000 men (some historians would put the figure as high as 36,000) to meet the enemy force of 6-7,000 men (or 9,000 if one follows the upper estimates). The experienced Constable and Boucicault, the Marshal of France, were both in agreement that the best strategy was to surround and starve the enemy into submission. Indeed, supplies were Henry's number one problem. However, the younger and impetuous French nobles overruled them and opted for a much riskier frontal attack in the hope of overwhelming the English with sheer numbers. The two armies met on Saint Crispin's day, 25 October 1415, near the village of Agincourt (Azincourt in French), some 75 km (45 miles) south of Calais. Four eyewitness accounts survive for Agincourt, two from each side, meaning that its details are better known than many other medieval battles.

As with the two great victories England had won previously in the Hundred Years' War at Crécy and Poitiers, the French made the fatal mistake of allowing the invaders to choose their own defensive position. This mistake may have been due to the French commanders underestimating the size of the English army. Henry marshalled his troops in a natural depression flanked by protective woodlands. The French would have to attack in a confined area, thus Henry had already gone some way to nullifying their vast numerical advantage. The English troops were arranged with archers on both flanks and at the front, and protected by 1.8 metres (6 ft.) sharpened stakes sticking out at an angle from the ground.

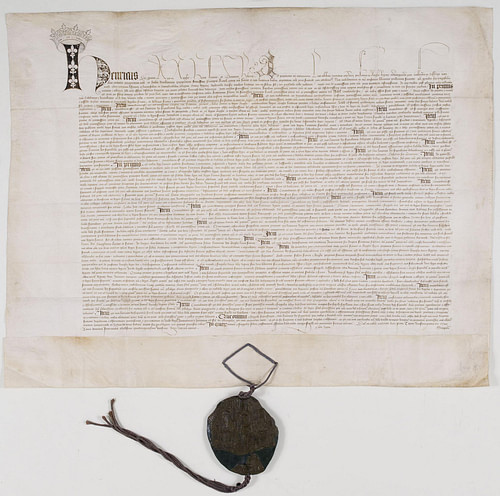

The French battle plan, discovered in a document which still survives today, seems to have been to have archers and crossbowmen just forward and to the side of the main body which was composed of men-at-arms in the centre and ordinary infantry either side. Then two large wings composed of heavy cavalry and support troops were to join the main body of the French army and push forwards, one wing attacking the right flank of the enemy and the other attacking the English rear. As so often in warfare, though, the plan got nowhere near to matching the reality of the day itself.

William Shakespeare in his play Henry V (1599) imaginatively gives the king these stirring lines as Henry rouses his army just before battle commenced:

And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by

From this day to the ending of the world

But we in it shall be remembered,

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; but he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition.

And gentlemen in England now abed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap while any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.

(Act 4, Scene 3)

The battleground was in a shocking state for horses, the recently ploughed fields and overnight rain presenting a sea of mud for both sides. The English had lighter armour than their French counterparts and this proved very useful in the battle conditions. In the event, the French were not so willing to enter the defile where Henry had stationed his troops and so he had them move a little forward to a slightly more exposed position to tempt the enemy into a rash charge. From descriptions, it seems the archers took their pointed stakes with them.

The French crossbowmen and archers first let off a few volleys, and then the cavalry charged, but these units were depleted in number because many nobles had left the lines during the long delay to start combat. Neither could the two cavalry wings attack the flank and rear of the English army as both sides were now protected by trees. Of those knights who did attack, many were knocked off their horses and had their armour pierced by the powerful English arrows being fired at them from multiple directions. The French attack was driven back onto its own now advancing infantry while a second cavalry wave came on top of the first wave, mostly on the flanks to avoid their own men.

Very soon the terrain was a mud swamp after the passage of so many horses and men while bodies piled up in heaps to further block the defile. The next stage of the battle saw men-at-arms fighting on foot on both sides, as well as the English archers now using their swords, axes and mallets, as the battlefield became even more chaotic and mud-clogged. There were now so many corpses and wounded that if an armoured knight fell down there was a good chance he would suffocate in the mass of writhing humanity and horses. Most of the third and rear French units at this point left the battlefield. Against all the odds, Henry V had led his men to a brutal victory.

The French losses were astonishing: around 7,000 men (again, higher estimates go up to 13,000). The English dead perhaps numbered as few as 500 (or under 1,000 according to some historians). One reason for the high mortality figures amongst the French was because towards the end of the battle Henry had ordered the execution of prisoners when he received news that a contingent of the enemy had attacked the English baggage train in the rear and a remnant of the third rank of French troops seemed still willing to fight. The king perhaps feared the battle might start anew and so did not want his men preoccupied with prisoners who themselves might take to fighting again. The result was a cold-blooded massacre for which French historians have never forgiven Henry ever since. Certainly, it was an embarrassing example of how the rules of medieval chivalry were not always met in the heat of battle.

Amongst the fallen at Agincourt were most of the French nobility, including three dukes, six counts, 90 barons, the Constable of France, the Admiral of France, and almost 2,000 knights. This culling of the French nobility meant there was limited resistance to Henry's next moves in terms of large field armies clashing. The king had, once again, led his troops from the front and won, even if he had received a heavy bash to his helmet (which now hangs over his tomb in Westminster Abbey) and had his golden battle crown smashed. There were some notable English casualties in the battle such as Edward Plantagenet, 2nd Duke of York, who had courageously led the English vanguard and the young Michael de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk.

Aftermath

Victory at the battle of Agincourt made Henry V a national hero in a country only just beginning to feel itself one nation. Henry's heroic status was evidenced by a magnificent welcome procession when the king returned to London in November 1415. The procession hailed Henry as a truly great English monarch and included choirs, maidens with tambourines, and banners proclaiming him the King of France. The passage through the capital included hundreds of captured French nobles who then had to suffer the additional tedious indignity of a thanksgiving service in Saint Paul's Cathedral. The most illustrious captive was Charles, Duke of Orleans, nephew of Charles VI, who eventually found himself a prisoner in the Tower of London for the start of his 25 years of confinement in England. Other notable captives included John, Duke of Bourbon; Charles of Artois, Count of Eu; Louis, Count of Vendôme; Arthur, Count of Richemont, and the Marshal, Boucicault, who had commanded the French vanguard and who was imprisoned in Yorkshire until his death four years later.

While the French henceforth studiously avoided all explicit mention of the battle of Agincourt and referred to it only as 'the accursed day', over the next five years Henry went on to capture Normandy via a series of sieges and then marched on Paris. Indeed, the English king was so successful that he was nominated as the regent and heir to Charles VI. The deal was signed and sealed in the May 1420 Treaty of Troyes. To cement the new alliance, Henry married Charles' daughter, Catherine of Valois (l. 1401 - c. 1437) on 2 June 1420 in Troyes Cathedral.

All this glittering English pride and pomp then came crashing down when Henry V unexpectedly died, probably of dysentery, in 1422. Already, the wheel of fortune was turning and the arrival of Joan of Arc (1412-1431) in 1429 saw the beginning of a French revival as King Charles VII of France (r. 1422-1461) took the initiative. The weak rule of Henry VI of England (r. 1422-61 & 1470-71) saw a final English defeat as they lost all French territories except Calais at the wars' end in 1453. England then descended into the insular dynastic squabbles that we today call the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487).