The Italian campaign of 1796-1797, waged by a young Napoleon Bonaparte, was a decisive campaign in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). It led to the defeat of Austria, the beginning of French control of northern Italy, and the end of the war, but most importantly, it launched Bonaparte himself to new heights of fame and power.

The War of the First Coalition, the first of the Revolutionary Wars, had been ongoing since 1792, fought between the French Republic and a coalition of anti-French powers. Yet most of the fighting had taken place in Flanders and Germany, leaving the Italian front as more of a sideshow. Upon taking command of the Army of Italy in March 1796, Bonaparte would make the Italian theater the most important operation in the war, stunning all of Europe as he beat every Austrian army sent against him and redrew the map of northern Italy. His brilliant campaign led Austria to sue for peace and end the war in October 1797 and made Bonaparte one of the most influential men in France.

To Destiny

On 27 March 1796, General Napoleon Bonaparte arrived in Nice to take command of the French Army of Italy. It had been a whirlwind of a month for the young general, who had received the command on 2 March, only seven days before marrying the attractive Joséphine de Beauharnais. Joséphine was the former mistress of Paul Barras, a member of the French Directory and one of the most powerful men in France, leading to rumors that Bonaparte had only received his command as a favor from Barras to his old paramour. Yet, by this point, Bonaparte had already built a reputation in the French army, having distinguished himself at the Siege of Toulon in 1793 and by crushing the royalist revolt of 13 Vendemiaire in 1795. Whatever the true reasons for his appointment, Bonaparte left for the front after a honeymoon of only 48 hours; as a wedding gift, he left his bride with a golden medallion inscribed with the words 'To Destiny'.

Upon arriving at Nice, General Bonaparte's first order of business was to hold a troop inspection. He was met with a ragged, demoralized force on the point of mutiny. The men were starving and malnourished, given only meager rations provided by corrupt contractors who charged extortionate prices. They lacked the most basic supplies; muskets, bayonets, and uniforms were all rare commodities, and entire battalions went without shoes. The army had not been paid for months, and when pay did arrive, it was in the form of the nearly worthless banknotes called mandats territoriaux, which was all the practically destitute French Directory could provide. Disease, desertion, and battlefield casualties had whittled the army down from an initial strength of 106,000 men in 1792, to only 37,600 men and 60 guns in March 1796, with no new replacements on the way. Bonaparte had his work cut out for him.

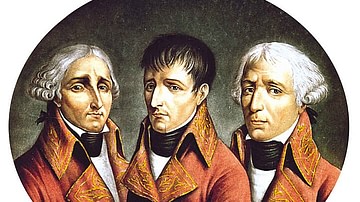

Bonaparte was also introduced to his officers, many of whom would become major players in the Napoleonic story. Bonaparte's chief of staff was Alexandre Berthier, an administrative genius whose ability to work 20-hour days and keep up with Bonaparte's rapid-fire orders kept the army's staff running like clockwork. The division commanders included Jean Sérurier, a gloomy general with 34 years of experience in the old Royal Army; Pierre Augereau, a former mercenary, dancing master, and duelist, who once killed an officer over an insult; and André Masséna, a talented general whose appetites for loot were only matched by his lust for women. Other soon-to-be famous officers under Bonaparte's command included Joachim Murat, Jean-Andoche Junot, Jean Lannes, Barthélemy Joubert, and Auguste Marmont. As David G. Chandler notes, "rarely had such a galaxy of military talent served together at one time and place" (57).

At first, these officers were unimpressed with their new commander-in-chief. At only 26, the short and wiry Bonaparte "looked more like a mathematician than a general", and the pleasure he took in showing off the portrait of his new wife made him seem juvenile. The generals would soon realize they had underestimated him. Immediately, Bonaparte reorganized the commissariat and threatened the venal contractors. He recalled the cavalry from winter quarters and quietly secured a loan of 3 million francs from Genoese financiers. He reintroduced discipline by disbanding mutinous battalions and court-martialing two officers for singing anti-revolutionary songs. Within days, Bonaparte had won the respect of his subordinates; as Masséna famously remarked, Bonaparte "donned his general's cap and seemed to grow by two feet" (Roberts, 75).

Bonaparte next tried to win over the rank-and-file soldiers, promising them the victories and riches that had hitherto only been afforded to their comrades in Germany and Flanders:

Soldiers! You are hungry and naked; the government owes you much but can give you nothing. The patience and courage you have displayed among these rocks are admirable, but they give you no glory-not a glimmer falls upon you. I will lead you into the most fertile plains on earth. Rich provinces, opulent towns, all shall be at your disposal ... soldiers of Italy! Will you be lacking in courage or endurance?

(Chandler, 53)

It was a bold promise, especially for a general who was yet to lead an army into battle. On 10 April, five days before Bonaparte intended to launch his campaign, he received word that 53,000 Austrian and Piedmontese troops were already bearing down upon him. The time had come for Bonaparte to meet his destiny.

The Little Corporal

The Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia had been at war with the French Republic since 1793, but its heart was not in the fight. The Piedmontese distrusted their Austrian allies, whose commander, Johan Beaulieu, had likewise been warned against trusting the Piedmontese. Therefore, it was Bonaparte's intention to drive a wedge between the two armies and defeat each one in turn. On 12 April, moving with astonishing speed, he attacked Montenotte, a mountain village where the enemy line was dangerously overextended. Masséna led his division around the enemy's right flank in the pouring rain and enveloped them. It was Bonaparte's first victory as commander-in-chief of an army; the Austro-Piedmontese lost 2,500 men to 800 French casualties.

In the following days, Bonaparte beat the Allies twice more at Millesimo (13 April) and Dego (14 April), where he succeeded in driving the retreating Piedmontese and Austrian armies apart. He launched an invasion of Piedmont, defeating the Piedmontese army a week later at the Battle of Mondovì (21 April), which left the road to the Piedmontese capital of Turin wide open. Piedmont-Sardinia sued for peace and accepted the Armistice of Cherasco on 28 April; in less than a month of campaigning, Bonaparte had knocked one enemy out of the war. Now, it was time to face the Austrians.

As part of the treaty of Cherasco, Bonaparte included a 'secret' clause, which allowed him to use the bridge at Valenza over the River Po; this news was leaked to Austrian General Beaulieu, who guarded the pass. However, this was just a ploy by Bonaparte, who actually crossed the river at Piacenza, c. 110 kilometers (70 mi) to the east. The Austrians were taken by surprise and were forced to pull back to protect the road to Milan. The French pursued and, on 10 May, intercepted the Austrians as they crossed the Adda River, at the town of Lodi. By the time the French arrived, most of the Austrian army was already across, and only a rearguard force remained in the town. The rearguard was driven back by grenadiers under General Lannes, but Bonaparte was now faced with the task of seizing the bridge across the Adda before the Austrians destroyed it. A company of carabiniers under Colonel Dupas accepted the suicidal task of leading the assault, and at 5 p.m., the French made a frenzied charge onto the bridge, into a hail of Austrian grapeshot. French soldiers waded into the shallows and fired up at Austrian gunners, while wave after wave of French assaults finally took the bridge.

By itself, the Battle of Lodi held little significance – the Austrians were already retreating, and both sides suffered equal casualties. Yet the battle showed the determined bravery of the French soldiers and soon took an important place in Napoleonic legend. Bonaparte's victory at Lodi earned him the love of his men, who gave him the affectionate nickname of "the Little Corporal". The battle also seemed to convince Bonaparte of the greatness of his destiny. He later wrote:

I no longer regarded myself as a simple general, but as a man called upon to decide the fate of peoples. It came to me then that I really could become a decisive actor on the national stage. At that point was the first spark of high ambition.

(Roberts, 91)

Fearing that Bonaparte was becoming too popular, the Directory in Paris proposed that he split the command of the Army of Italy with the more experienced General Kellermann of the Army of the Alps; Bonaparte not only refused to share command but threatened to resign if he was forced to. Unwilling to risk losing their most successful general, the Directory abandoned the scheme.

Entering Milan

On 15 May 1796, the Army of Italy entered Milan to great fanfare and acclaim from the populace, which was glad to see the back of the Austrian army. Bonaparte immediately set about reorganizing the Milanese government into a new 'sister republic', or French satellite state, that became the Transpadane Republic. Bonaparte helped draft the republic's constitution, appointed Italian Jacobins to the government, and ensured the foundation of pro-French political clubs. Despite this mask of liberation, Bonaparte still had an army to pay, and he levied a total of 20 million francs from Milan and the dukes of Parma and Modena. Thus, the Army of Italy was paid in hard cash for the first time since 1793. Bonaparte turned a blind eye as his generals looted the city and sent priceless works of art back to Paris.

On 21 May, he departed for Mantua, where Beaulieu had holed up with his army. But no sooner had he left than he received reports of rebellions breaking out in Milan and Pavia. Bonaparte swiftly returned and wrought severe retribution on the Italian rebels. He stormed the gates of Pavia and let his men sack the city without restraint for several hours, while General Lannes took vengeance on the rebellious town of Binasco, shooting all the men and burning the houses down. Such brutality was meant to warn the rest of occupied Italy of the cost of defying their French 'liberators'.

Besieging Mantua

Mantua was part of the Quadrilateral, a collection of four fortresses that guarded the Alpine passes and held the key to Austrian control of northern Italy. Therefore, when Bonaparte besieged Mantua on 2 June with a reinforced and resupplied army, it was vital for the Austrians to prevent it from falling. Field Marshal Dagobert von Wurmser, a veteran of the Seven Years' War, was given command of 50,000 troops and ordered to relieve the Siege of Mantua at all costs. To move more swiftly, Wurmser decided to divide his army: 18,000 men under his lieutenant, General Quasdanovich, would advance down the west side of Lake Garda while Wurmser himself led the remaining 32,000 down the east side. When Bonaparte caught wind of this advance, he knew he had to defeat each army before they had a chance to coalesce.

At the end of July, Bonaparte ended the siege of Mantua, abandoning 179 cannons and mortars and dumping their ammunition into the lakes. On 3-4 August, he beat Quasdanovich at the Second Battle of Lonato, and he defeated Wurmser at the Battle of Castiglione the next day. After losing some 5,000 men across both battles, the Austrians were forced to retreat, allowing Bonaparte to return to Mantua to continue the siege. Wurmser regrouped and attacked again at the end of August. He met Bonaparte in a series of battles but was defeated at the Battle of Bassano on 8 September. Still hoping to relieve the siege, Wurmser retreated toward Mantua, but another defeat at the hands of General Masséna forced him into the city. Now with the addition of Wurmser's men, there were not enough supplies to feed the entire garrison. When Bonaparte promptly resumed the siege, the Austrians quickly had to resort to eating horseflesh; before long, disease and malnutrition carried off 150 soldiers per day, as well as countless civilians. Despite the suffering, Wurmser refused to surrender.

Abandoned in the Depths of Italy

In November, the Austrians made a third attempt to lift the siege. This time, they were commanded by the 61-year-old Hungarian General József Alvinczi, who Bonaparte would later praise as his most capable adversary in the Italian campaign. On 2 November, Alvinczi crossed the Piave and sent forces under Quasdanovich ahead of him to take Vicenza via Bassano. On 6 November, Bonaparte tried to stop Quasdanovich's advance at the Second Battle of Bassano, but the French general found himself outnumbered and was forced to withdraw; it was the first real defeat of Bonaparte's career. Falling back to Vicenza, Bonaparte received word that a French division under General Vaubois had suffered a crushing defeat near Cembra and Calliano. Needing to reassert discipline, Bonaparte removed Vaubois from command and harangued his men, saying, "Soldiers of the 39th and 85th Infantry, you are no longer fit to belong to the French Army ... the chief-of-staff will cause to be inscribed on your flags, 'these men are no longer part of the Army of Italy'" (Roberts, 120). These humiliated demibrigades fought with extra vigor in the coming fights.

On 12 November, Bonaparte held Verona against an onslaught of Austrian troops, and both sides rested the following day. This was undoubtedly the bleakest moment in the campaign, as evidenced by Bonaparte's despairing letter to the Directory: "Perhaps the hour ... of my own death is at hand ... we are abandoned in the depths of Italy" (Chandler, 103). But Bonaparte was not about to admit defeat; on 15 November, he attacked Alvinczi at the Battle of Arcole, with most of the fighting taking place around a bridge over the Adige River. After an initial attempt to seize the bridge by Augereau's men was repulsed, Bonaparte seized a flag and led the second charge himself. The charge became bogged down on the bridge, and Bonaparte's aide-de-camp was killed beside him; Bonaparte would probably have been killed himself, had he not been knocked off the bridge and into the marshy ground beneath. It took two more days and 3,000 casualties, but the French ultimately seized the bridge and won the battle.

Victory

After Arcole, Bonaparte continued to lay siege to Mantua. Of the 18,500 soldiers garrisoned in the city, only 9,800 were fit for duty, and the city's rations were expected to run out by 17 January. If Austria wanted to lift the siege, it had to do it soon. A fourth and final attempt was made by Alvinczi, and the two armies clashed once again on 14 January 1797 at the Battle of Rivoli. It was a resounding French victory; while the French lost 3,000 men, the Austrians suffered 4,000 killed and wounded and lost an additional 8,000 captured. Rivoli dashed the last hopes of Mantua; they finally surrendered on 2 February. 16,300 Austrian soldiers had died of starvation and disease since the siege began, along with thousands of civilians.

The fall of Mantua opened Bonaparte's army to its ultimate objective: Vienna. On 10 March 1797, Bonaparte led 40,000 men through Tyrol to Klagenfurt and then to Loeben in Styria, where they could apparently see the spires of Vienna, 160 kilometers (100 mi) away. Bonaparte fought a few minor battles against Archduke Charles, brother of the Austrian emperor, but the Austrians dared not risk a major fight, as they were still threatened by the French armies on the Rhine. The Austrians decided to sue for peace, and Bonaparte accepted their offer for an armistice at Loeben on 2 April. The details of this armistice were finalized on 17 October 1797, with the Treaty of Campo Formio. The War of the First Coalition was over.

Bonaparte overstepped himself by negotiating on behalf of the French Republic, not even bothering to consult the Directory. He got Austria to acknowledge French control of Belgium and the left bank of the Rhine, as well as the creation of a new sister republic in Italy, the Cisalpine Republic. In compensation for Austria's territorial losses, Bonaparte offered it lands belonging to the neutral Serene Republic of Venice, an ideal sacrificial lamb; Venice was thereby partitioned between Austria and the Cisalpine Republic, ending the serene republic's 1,200-year existence.

Conclusion

The Italian campaign of 1796-97 saw the dawn of a new era. While it contributed significantly to France's victory in the French Revolutionary Wars, it was perhaps more important for its role in the creation of Napoleon Bonaparte. Bonaparte became a celebrity in Paris and found himself renowned throughout Europe. His generals, many of whom would go on to serve as Napoleon's marshals, earned fame and glory in Italy. Not even 28 years old, Bonaparte had changed the map of northern Italy, given life to republics, humbled one of Europe's foremost powers, and achieved heights of popularity at home. But despite all this, the story of Napoleon was only just beginning.