Esoteric Buddhism is the mystical interpretation and practice of the belief system founded by the Buddha (known as Sakyamuni Buddha, l. c. 563 - c. 483 BCE). It is known by several names and is characterized by a personal relationship with a spirit guide or deity who leads one to enlightenment.

An initiate must first study with a master who shares writings, teachings, and knowledge not widely known and often referred to as "secret". The student masters various meditation techniques and studies the tantra, generally understood to mean "the continuum" as expressed in Tantric texts. This continuum is the pattern of universal love and compassion shown throughout time by the supernatural entities of buddhas, of which Sakyamuni Buddha was only one, to humanity.

An adherent of Esoteric Buddhism forms a relationship with one of these buddhas and is then spiritually led by the entity (or deity) on the path toward enlightenment as a bodhisattva. Vajrayana Buddhism (also known as Tibetan Buddhism) is regarded as a form of both Mahayana Buddhism and Esoteric Buddhism as it combines elements of both, and most schools, like Zen Buddhism, follow this same pattern in taking what works best from other schools to supplement the foundational teachings.

The beliefs and practices of Esoteric Buddhism are not as well known or widely recognized as those of the popular Mahayana Buddhism because they are not supposed to be. The belief system is open only to those who feel called to follow it and are willing to submit themselves to instruction by a master. The belief system may have developed as a reaction to the Hindu Revival of the 8th century CE inspired by the work of the philosopher Shankara (though this claim is challenged), which emphasized many of the same aspects of faith and knowledge later espoused by Esoteric Buddhism, including foundational knowledge, submission to a master’s teaching, and the importance of personal revelation.

Early Religious Reform

During the Vedic Period (c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE) in the region of modern-day India, the belief system known as Sanatan Dharma ("Eternal Order"), better known as Hinduism, developed from earlier beliefs through the written works known as the Vedas which preserved a much older oral tradition. Hinduism was highly ritualized at this time. The Vedas ("knowledge") were composed in Sanskrit which most people could not understand, and the priests needed to interpret the texts, which were thought to explain the universe, human life, and how one should best live it.

The Vedas maintained that there was a divine being, Brahman, who both created and was the universe. A spark of the divine (the atman) was within each person, and the purpose of life was to awaken this spark and live virtuously so that, after death, one’s own divine light would merge with Brahman in eternal unity, and one would be freed from the cycle of rebirth and death (known as samsara), which was associated with suffering.

Around 600 BCE, a religious reform movement swept across India that questioned orthodox Hinduism. Different schools of thought developed at this time known as astika ("there exists"), which supported the Hindu claim regarding the existence of the atman, and nastika ("there does not exist"), which rejected that claim as well as almost all of the Hindu vision.

The most famous nastika schools of the time were Charvaka, Jainism, and Buddhism. The first was entirely materialistic and denied the existence of the soul. The second two, while also denying the Hindu atman, recognized a self undifferentiated from the universe which suffered under the illusion it was a separate self distanced both from its source and from other selves in the world.

Buddhism: Establishment & Development

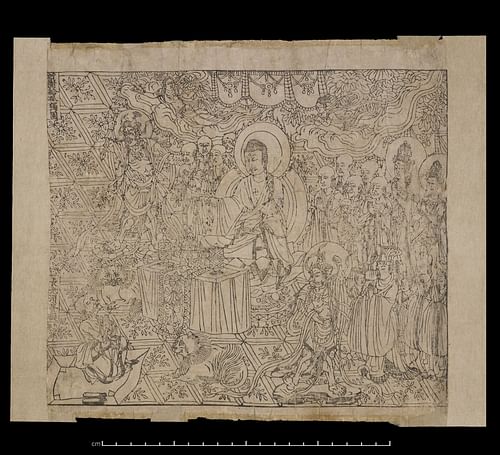

Buddha, according to tradition, was a Hindu prince named Siddhartha Gautama who renounced his position and wealth to seek spiritual enlightenment. He realized that suffering comes from attachment to transitory aspects of life and life itself, which was in a constant state of change and so could not be held, kept, or controlled, but which people insisted should be lasting. One suffered by continually insisting on an impossible permanence. By recognizing this, and following a path of non-attachment, one could attain nirvana ("liberation") at one’s death, freeing the self from samsara and attendant suffering.

Buddha founded his system on acceptance of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path and taught his disciples a spiritual discipline whereby they could attain individual enlightenment just as he had. On his deathbed, he requested that no spiritual leader be chosen to replace him and each of his disciples should continue on his own path. After his death, however, a leader was chosen, and rules were written, and Buddha’s teachings were institutionalized.

The new faith splintered in 383 BCE over doctrinal differences, and many Buddhist schools developed including Sthaviravada and Mahasanghika, which would encourage still more. Buddhism at this time was vying with the more firmly established religions of Hinduism and Jainism for adherents and made little headway until it was embraced by Ashoka the Great (r. 268-232 BCE) of the Mauryan Empire who not only helped establish the system in India but spread it to Sri Lanka, Korea, Thailand, China, and Japan.

Shankara & Hindu Revival

Buddhism was enthusiastically received in these other lands but continued to struggle to gain and hold followers in India. Hinduism offered a greater variety of ritual and pageantry while also advancing the concept that everyone held a spark of the divine, was in fact a divine being and part of the universe, which contrasted sharply with the Buddhist doctrine of emptiness-of-self and simplicity of observance.

Buddhist efforts at conversion were hampered further by the Hindu Revival of the 8th and 9th centuries CE encouraged (according to tradition, at least) by the sage Shankara who advocated the doctrine of Advaita Vedānta ("non-duality") emphasizing the ultimate reality of Brahman, the existence of the atman, and the illusory nature of all else. Only Brahman existed and human beings existed, through the atman, as parts of Brahman. Shankara attacked Buddhist thought for its denial of the atman, but his understanding of liberation through oneness of the atman with Brahman is similar to the Buddhist concept of attaining nirvana through non-attachment.

Shankara’s doctrine relied on an adherent accepting a program based on revelation of ultimate reality. The program had four aspects of equal importance:

- Śāstra – scriptures

- Yukti – reason

- Anubhava – knowledge through experience

- Karma – spiritually relevant actions

A student submitted to a teacher who helped them understand scripture, apply reason and experience to interpretation of scripture, and act correctly on that interpretation. According to some scholars, this paradigm directly influenced Esoteric Buddhism. According to other views, the fundamentals of Esoteric Buddhism, especially a personal relationship with a spirit or deity, were already centuries old by the time Shankara appeared. In this view, Shankara may have influenced the 8th century CE form of Esoteric Buddhism, but his doctrine did not inspire or inform the fundamental beliefs and practices.

Esoteric Buddhism in India

Esoteric Buddhism is also known as Mantrayana ("mantra vehicle"), Guhyamantrayana ("secret mantra vehicle"), Tantrayana ("tantra vehicle"), and Vajrayana ("diamond vehicle"). The first three names have to do with the importance of revelation through written works – mantras and tantras – while the last with the value of the experience which leads to a truth as valuable and unbreakable as a diamond. According to some traditions, each of these four was/is a unique school but all share in the same essential understanding and, more or less, are the same belief system.

A mantra (literally "spell" or "charm") is recited to clear and protect the mind from illusion. It may be one word or even one syllable (as in the case of Om, the sacred syllable), a sentence, or a series of sounds. A tantra ("continuum") is a handbook, a manual on how to progress spiritually. Scholars Robert E. Buswell, Jr. and Donald S. Lopez, Jr. comment:

In Buddhism, the term tantra generally refers to a text that contains esoteric teachings, often ascribed to Sakyamuni or another buddha. [Tantras may include] mantra, mandala, mudra, abhiseka (initiations), homa (fire sacrifices), and Ganacakra (feasts), all set forth with the aim of gaining siddhi (powers) both mundane and supramundane. The mundane powers are traditionally enumerated as involving four activities: pacification of difficulties (santika), increase of wealth (paustika), control of negative forces (vasikarana), and destruction of enemies (abhicara). The supramundane power is enlightenment (bodhi). The texts called tantras began to appear in India in the late seventh and early eighth centuries CE, often written in a nonstandard Sanskrit. (894)

The dates of the tantras correspond to the activities of itinerant yogis known as mahasiddhas. A siddha was a spiritual ascetic and a mahasiddha a "great" or "perfected" siddha. These yogis were known to frequent charnel grounds (above-ground cemeteries where bodies were left to decompose as part of mortuary rituals) and associated themselves with the transitional sphere between life and afterlife. They claimed to be able to interact with powerful spirit-deities like the Naga, Yakshas, and dakini as well as the spirits of the departed.

Although Buddhists themselves, they challenged mainstream Buddhism on the grounds it was too ritualistic and had strayed from the teachings of Sakyamuni Buddha. The siddhas claimed they possessed the true teachings of the Buddha which had been given in secret to a select few prior to his death. They were informed, they claimed, by supernatural forces, including the female bodhisattva Tara, a savior figure who protected adherents from danger and was the manifestation of divine compassion. The siddhas’ interpretation of Buddhism was well received by the Pala Dynasty of the Kamarupa Kingdom (900-1100 CE) who encouraged its growth until two forms of Buddhism, difficult at times to differentiate, both flourished in Bengal. Scholar John Keay comments:

In eastern India the demarcation between Buddhists and non-Buddhists was further blurred by both countenancing the efficacy of mantras (repetitious formulae), yantras (mystical designs) mudras (finger postures) and the numerous other practices associated with Tantracism…The rituals and disciplines involved were complex and secret. Some mimicked the sexual imagery of myths involving the union of the deity and his shakti, or female counterpart. Breaking the taboos of caste, diet, dress, and sexual fidelity, practitioners might enjoy both a liberating debauch and an enhanced reputation, even if magical powers eluded them. (194)

The siddhas and their followers drank alcohol, engaged in various sex acts, refused to recognize caste or social status, and claimed their freedom from social norms was granted and approved of by supernatural entities that had always existed. Their primary goal was for each person involved to become an awakened bodhisattva by recognizing that social norms were simply a trap that kept one chained to the world of illusion and suffering. Instead of renouncing aspects of life in practicing non-attachment, they indulged in all life had to offer in the belief that, as they pursued enlightenment, these earthly pleasures would no longer interest them and, based on later writings anyway, they seem to have been correct.

The claims of the medieval siddhas eventually evolved into or were absorbed by adherents of Vajrayana Buddhism which developed in Tibet and was systematized by the sage Atisha (l. 982-1054 CE) taking the form recognized today as Tibetan Buddhism, which is a form of Esoteric Buddhism. Adherents must submit to the discipline of a teacher who encourages transformation and empowerment by the transmission of secret knowledge. The basic form of instruction is quite similar to that of Shankara’s 8th-century CE program in that scriptures are used as a base on which to build spiritual experience, exercise reason, and perform spiritually relevant actions that move one closer to becoming a bodhisattva who can then help others along the same path.

Esoteric Buddhism in China & Japan

Esoteric Buddhism arrived in China via the Silk Road in the early 7th century CE and was embraced by the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). Buddhism had been introduced centuries earlier following the missionary efforts of Ashoka and so the Chinese were already acquainted with the basic teachings and overall message. Tantric Buddhism, however, claimed to offer a more immediate experience of spiritual enlightenment and became more popular than the mainstream version. Great Buddhist masters traveled to China to help develop centers of learning and translate texts, and Chinese scholars regularly went to India to find and bring back copies and translations of more.

India was recognized as the birthplace of Buddhism and scholars traveled there specifically to find, translate, and bring back whatever they could find. Among these is the famous Xuanzang (l. 602-644 CE) who defied the imperial edict of the Chinese emperor Taizong (r. 626-649 CE) against foreign travel to go to India in 627 CE. He is well known for translating the Heart Sutra from the Perfection of Wisdom, which remains the most popular and often recited by Buddhists in China and around the world.

Indian Buddhist scholars were invited to China to teach and translate, and the Chinese collection of Buddhist texts grew under their guidance. The translated texts regularly tried to imitate the originals as closely as possible as scholars Forrest E. Baird and Raeburne S. Heimbeck note:

Undeniably the text [of these works] exhibits some of the trappings of an Indian Buddhist text, including many Sanskrit technical terms and doctrines of Indian origin. In an age when Chinese Buddhists were looking to India for the authentic Buddhism, giving a Chinese composition a Sanskrit veneer would make its presentation of a belief in the Absolute more credible. (435)

The belief system traveled from China to Japan where it was famously encouraged by Prince Shotoku (r. 594-622 CE) who helped to establish it throughout the country. Esoteric Buddhism was refined, systematized, and spread further by Kukai (also known as Kobo Daishi, l. 774-835 CE), a scholar-monk and poet who founded Shingon Buddhism in Japan. Shingon ("True Word") Buddhism adhered to the cosmic vision of Buddhism as an eternal set of strictures which had been articulated clearly by the Buddha but not conceived of by him, nor had he been the first buddha and certainly not the last. Shingon, like Vajrayana Buddhism, claimed one could attain complete enlightenment in one’s lifetime and only by submitting to the discipline of a virtuous teacher.

Conclusion

Mainstream Buddhism emphasized adherence to the Eightfold Path after a recognition of the Four Noble Truths which led one to enlightenment and freedom, at death, from the cycle of rebirth. Esoteric Buddhism offers the same basic platform but claims one can attain results more quickly by embracing and then letting go of the attachments of life as one becomes more spiritually mature. One should not, then, renounce the world of illusion but recognize its value since one could not accrue spiritual merit without it and, without the spiritual merit one earned through the discipline of distancing oneself from that world, one could not advance toward enlightenment.

Buswell and Lopez note how one of the names for Esoteric Buddhism is Mantrayana and the importance of reciting a personal mantra in staying the course toward higher values. They further comment:

According to one popular gloss, the term mantra means "mind protector", especially in the sense of protecting the mind from the ordinary appearances of the world. In this sense, the mantrayana would refer not simply to the recitation of a mantra but to the entire range of practices designed to transform the ordinary practitioner into a deity and his ordinary world into a mandala. (530)

The final goal of Esoteric Buddhism, as with any Buddhist school, is enlightenment and compassionate living. Adherents of Esoteric Buddhist schools claim a special knowledge, distinct from other schools, better able to advance their spiritual goals but, at the same time, recognize that their school is only one aspect of Ekayana ("One Vehicle" or "One Path") in which all Buddhist schools participate, and what is most important is not which school one chooses to belong to but how one chooses to live the Buddhist principle of universal compassion and enlightened detachment in the best way possible.