Erebuni was an Urartian fortress and city, located between the Nor Aresh District and the Vardahsen District on the outskirts of present-day Yerevan, Armenia, and situated on top of Arin Berd hill. In Armenian, the fortress and archaeological site is known as “Arin-Berd” or the “Fortress of Blood,” and the name of this fortress city endures in the word “Yerevan,” which is the capital of Armenia. First constructed during the reign of Arguishti I (r. 786-764 BCE) around the year 782 BCE - some 20 years before the founding of Rome - Erebuni is typically described by historians and archaeologists as one of the mightiest and most impressive Urartian structures in existence.

Erebuni became the primary residence of the Urartian royal family, and thus emerged as a settlement of political and cultural importance in the Near East. Following the collapse of the Urartian states in the early 6th century BCE, Erebuni retained much of its population and importance as the capital of the Persian Satrapy of Armenia under the Achaemenid Empire by the end of the 6th and early 5th centuries BCE. Its strategic location ensured the city's survival as a political and administrative center under independent Armenian kings in antiquity, and the site has been continually inhabited since its founding, expanding further as it developed into the medieval and modern city of Yerevan.

Historical Overview

Erebuni was the first Urartian fortress constructed north of the Araxes River in the Armenian highlands, and it owes its genesis to the ambitions and martial appetites of Arguishti I who was the sixth king of Urartu. Arguishti I, the archrival and nemesis of Shalmaneser IV of Assyria (r. 783-773 BCE), was responsible for expanding Urartian power and influence into Asia Minor, the Caucasus, and even what is present-day northern Syria. Urartian power reached its zenith during Arguishti's reign, and Erebuni is a testimony in monumental form to his aspiration of projecting Urartian might and power. Needing to secure and delineate political power throughout his domains, Arguishti I ordered the construction of two major fortresses in what is present-day Armenia: Erebuni in 782 BCE and Argishtikhinili in 776 BCE. Rusa II (r. c. 680-639 BCE) continued this policy by building Teishebaini in the mid-7th century BCE. Unlike neighboring polities in Asia Minor and the Near East, Urartu had localized, political traditions characterized by networks of interlinked and interspersed fortresses rather than massive urban settlements. Uratian kings, like Arguishti I, hoped that compact and strategically positioned fortresses like Erebuni would be able to withhold sieges from large foreign armies and prevent their penetration of the Urartian interior.

During the Urartian period, Erebuni emerged as a political and cultural center while Argishtikhinili, located 5 km (3 miles) north of the Araxes River and 15 km (9 miles) from modern day Armavir, Armenia, developed primarily into an economic center. According to cuneiform inscriptions found at Erebuni and in Van, Armenia, Arguishti I brought 6,600 captives from Hatti and Supani to Erebuni to help populate the city. (This is attested by cuneiform inscriptions in Van and also those found by Soviet excavators while Armenia was part of the USSR.) Although the fortress and city remained affluent, Arguishti I's military prowess was never matched by his successors.

Faced with Assyrian, Cimmerian, Scythian, and Median enemies, Urartu declined in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE. Despite being raided by Cimmerian forces and the transference of much of its populace and wealth to the Teishebaini fortress, the Erebuni fortress survived and was occupied by the Median Empire around 585 BCE. Due to its prime geographical location, Erebuni became a flourishing political center once again, albeit under the control of the Persian Achaemenid dynasty (550-330 BCE). The Persians undertook large-scale reconstructions of the fortress and Erebuni became the capital of the Persian Satrapy of Armenia. Despite the fact that Persian power collapsed due to the conquests of Alexander the Great (r. 332-323 BCE) in the 4th century BCE, the settlement at Erebuni continued to grow, eventually spreading outwards from the fortress' ancient walls. Artaxata replaced Erebuni as an Armenian capital around c. 188 BCE.

ArchitecturE

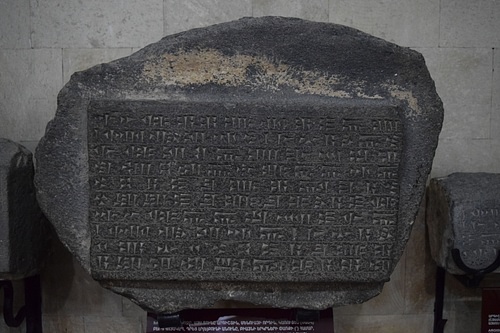

Situated on the Arin Berd hill and occupying a space of nearly 40 hectares (99 acres), Erebuni offered commanding views of Mount Ararat and access to the fertile Ararat Plain. The citadel of Erebuni occupies nearly 3 hectares (7 acres). Surrounded by defensive walls - in parts up to 15 m (49 ft) in height and 3-4 m (10-13 ft) in width - Erebuni was accessible from an eastern entrance, which offered strategic views of the three-range defensive walls in addition to the Ararat Plain. The main road that led to the citadel rose from the southeastern slope of the hill at a height of 2 m (6.5 ft) and terminated at the fortress' entrance. The entrance walls contained two cuneiform inscriptions:

By the greatness of Gold Chaldis, Argistis, son of Menuas, built this mighty stronghold and proclaimed it Erebuni. The land was desert. For the glory of the country of Biainili and for holding the enemy's countries in awe, by the greatness of God Chaldis, Argistis, son of Menuas, mighty king, king of the country or Biainili, ruler of the town of Tushpah.

It is likely that the citadel's monumental gate was solid and wooden, and opened to a large central square, which in turn was oriented from the southeast to the northwest. Special sections of the Erebuni fortress served different administrative, residential, and religious purposes: southeast of the main square was the religious section of the fort, including the temple of the Urartian god Khaldi; northwest of the square was occupied by the royal palace, administrative offices, and a temple dedicated to the Urartian god Ivarsa; and to the northeast of the square were residential homes and commercial buildings. Archaeological remains indicate that a ziggurat may have existed on the site too.

The royal palace at Erebuni was especially splendid according to the archaeological remains that have since been uncovered. Archaeologists have determined that the Persians made alterations and reconstructed parts of the administrative complex in the 6th century BCE. Originally, it contained a great hall decorated with frescoes of human figures and natural scenes with wild animals painted in rich hues. After the reign of Sardury II (r. 764-735 BCE), archaeologists suspect that the great hall of the royal palace was turned into a cellar, filled with enormous water and wine jars that could hold up to 40,000 liters (10,567 gallons) worth of liquid. Archaeologists have also uncovered five basalt pillars in the southeastern section of the fortress, which contain inscriptions dating to the reign of Arguishti I. It is believed that a powerful earthquake occurred during the reign of Rusa II, which destroyed parts of the city and palace.

Khaldi's temple was also decorated with beautiful frescoes, but the Persians later modified the basic temple plan into a rectangular plan during the 6th century BCE. The Persians additionally converted one part of the temple into a pillared hall (apadana). There was a fire temple at Erebuni, and contrary to what would have been considered proper by the Achaemenids, the Armenians sacrificed horses to the sun god, according to the Greek historian Xenophon (c. 430-354 BCE).

Excavations & Impact on Armenian Culture

The first major excavations at Erebuni began in 1950, under the archaeologist K. Hovhannisyan. A series of Soviet archaeological excavations lead by Konstantin Oganesyan in 1961 and 1969 CE later uncovered most of the artifacts that one sees today in the Erebuni Historical and Cultural Reserve. These excavations revealed a substantial and rich array of cereal and botanical materials preserved after thousands of years. (Archaeologists uncovered grape seeds, sesame oil, lentils, pea, and malted barley for the brewing beer.) Sadly, the massive restoration project of Erebuni fortress in the 1970s CE, which coincided with the 2,750th anniversary of its establishment, did irrevocable harm to the site and its integrity.

Since the collapse of the USSR in 1991 CE and the beginning of hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan, there were fewer investigations of the site in the 1990s and early 2000s CE. Recent excavations have focused on Erebuni's later occupations under the Medians, Persians, and Greeks. The imprint of Erebuni on the culture and popular imagination of modern Armenia is undeniable and ubiquitous. The names, symbols, and artifacts associated with Urartian heritage and art have become commonplace as is evidenced by decorative items and company advertising.

This article was made possible with generous support from the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Knights of Vartan Fund for Armenian Studies.