Cochineal is a brilliant red dye extracted from the crushed bodies of parasitic insects which prey on cacti in the warmer parts of the Americas. The dye was an important part of trade in ancient Mesoamerica and South America and throughout the colonial era when its use spread worldwide. Even today, cochineal continues to be used in foodstuffs and cosmetics.

Cacti & Bugs

The insects required to make cochineal red dye are females of the Dactylopius coccus which feed on the nopal cactus (aka the prickly pear cactus) in tropical and subtropical areas of the American continent and in some highlands in South America. A massive amount of insects is required, some 25,000 live insects or 70,000 dried ones to make around 450 grammes or one pound of dye. Only a few millimetres in length, the insects were so small that there was confusion over what they actually were, most thought them a worm that derived from a berry turning rotten. Not until the arrival of the microscope and the work of Nicolaas Hartsoeker in 1694 and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek in 1704 did science shed its light on the subject of just what was the source of this brilliant red dye.

The insects are collected from cacti and then subjected to extreme heat before being crushed, the precise method and temperature used dictate the colour shade of the resulting dye, produced by the presence of carminic acid. Cochineal red dye ranges in colour shades from orange to scarlet. Pure cochineal dye was also used to make other red-based colour pigments such as lake and carmine. Cochineal dye is particularly effective at bonding with natural animal fibres like silk, rabbit hair, feathers, and the wool of sheep, llamas, and alpaca.

Pre-Columbian America

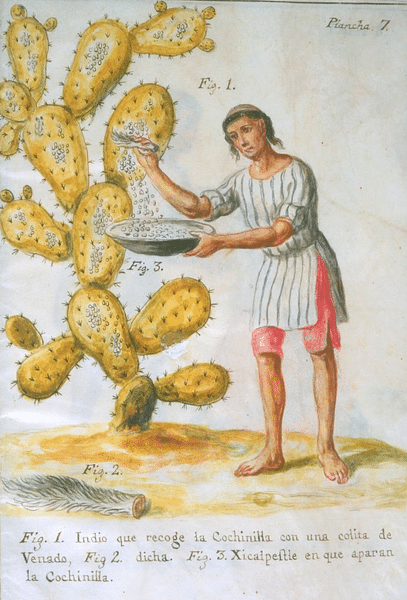

In ancient Mesoamerica from at least as early as the 2nd century BCE, the insects were cultivated on cacti by 'painting' eggs onto the palms of wild cacti using a fox hair brush. The mature insects were then collected from the cacti using a small spoon-like implement and simply dried out in direct sunlight, or sacks of them were placed in a heated room like a sauna. Studies have revealed that, over time, the selection of larger and more potent insects for domestication led to an even brighter red colouring than was available in the wild. The areas of Mixteca, Oaxaca, and Puebla were noted for their production of cochineal, and both the Aztecs and Maya produced, traded, and exported cochineal dye. In addition, cochineal dye was one of the valuable items extracted as tribute from conquered tribes.

Ancient Mesoamericans used the dye for clothing and as ink for writing, to illustrate maps, and in mural painting. Good examples of murals using cochineal can be seen at sites such as Monte Alban, capital of the Zapotec civilization from c. 500 BCE to c. 900 CE. Surviving bark paper tribute documents represent cochineal as a small bag tied at the top and covered with red dots. We know that prepared cochineal dye was transported in small leather sacks and that, alternatively, the raw material of dried insect carapaces could be mixed with flour or another substance to make flat cakes for ease of transport.

For the Maya and the Aztecs, red represented the cardinal direction East and had such obvious associations as blood. Indeed, in the Nahuatl language, cochineal dye is called nocheztli, which means the "blood of the prickly-pear cactus". Cochineal dye was also produced in Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru, where it was known as magno or macnu. It was prized by the Incas, who particularly valued finely-made textiles. Red was a powerful symbol of authority and can be seen, for example, in the striking tunics worn by Inca warriors and the long red robes reserved for nobles. The Inca ruler was the only person permitted to wear the head tassel or fringe known as the mascaypacha, which was brilliant red in colour.

Colonial Production

European dyers had been using kermes (extracted from the beetle of that name) since the Phoenicians began trading it in the first millennium BCE, but it was not as bright as cochineal. The madder root (Rubia tinctorum) was used to produce a red dye 45 times cheaper than kermes (in 1505), but it was an even duller, inferior red. Neither these competitors nor others such as Polish cochineal (Porphyrophora poloni), Armenian cochineal (Porphyrophora hameli), or Indian lac (Kerria lacca) – all made from types of parasitic insects – could compete with cochineal's brightness or fast-dying properties, which were ten times greater than the best of the rest.

Consequently, making cochineal dye became a highly lucrative business in Spanish America. Cochineal was on the list of items extracted as tribute from conquered communities. To meet the demand that tributes could not, Spanish colonialists grew cacti on large-scale plantations known as nopalerias. Such plantations dominated areas in Mexico and soon spread further afield such as the western highlands of Guatemala, and, in the same country, at Totonicapán, Suchitepequez, Guazacapán, and along the shores of Lake Atitlán. There were numerous nopalerias in northern Nicaragua, too.

Labour-intensive, the dye-making process was made possible in the colonial period through the use of forced labour in the encomienda and repartimiento systems. The collection method can be seen in such illustrated documents as the c. 1599 Cochineal Treatise, now in the British Museum, London. Labourers are shown being supervised by a Spanish noble as they scrape or brush the insects off the large flat paddle-like branches of the cacti into collecting bowls.

The historian B. C. Anderson gives the following summary of the early success and geographical spread of cochineal use:

Its main routes were first from New Spain to Seville and later, after 1520, to Cadiz. By the 1540s, it had reached France, Flanders, England, Livorno, Genoa, Florence, and Venice. From Venice it went to the Levant, Persia, Syria (especially Isfahan, Aleppo, and Damascus), Cairo, and India, as well as to Constantinople and the ports on the Black Sea and the Caspian region. By the 1570s, it had gone from New Spain to East Asia via Acapulco and the Philippines.

(339)

At the beginning of the 17th century, the trade was at its peak with some 250-300,000 pounds (113-136 tons) of dye being shipped to Spain each year. Cochineal was, therefore, one of the precious cargoes of the annual Spanish treasure fleets that crossed the Atlantic from Veracruz in Mexico to Havana in Cuba and on to Europe. In this period, cochineal and related dyes found an insatiable market with European textile manufacturers. So lucrative was cochineal production that there were limitations on just who could produce it. A document from the cabildo (council) of Tlaxcala in central Mexico, which dates to 1553, indicates that local Spanish aristocrats were not at all happy that some commoners amongst colonial settlers were also harvesting insects for dye production.

Cochineal collection and exports from the Americas also boomed in the early 17th century following the decline of cacao production but suffered a crisis from 1616-18, likely due to plagues of crop-ravaging locusts. After this devastation, cochineal production was mostly restricted to plantations in Mexico but remained an important industry. Indeed, in the 18th century, only silver was a more valuable export than cochineal (but a very long way ahead), and the Oaxaca region of Mexico employed some 30,000 people in the dye industry.

The Spanish were keen to keep the secrets of cochineal to themselves and prohibited the export of live insects outside the Spanish Empire. Further, only the ports of Seville and Cadiz were permitted to import cochineal in the 16th century. The monopoly could not last, though, for such a popular product as cochineal dye. There were cases of foreign spies visiting plantations and even thefts of cacti loaded with parasites, but attempts to produce cochineal on a large scale on other continents were not usually successful. The notable exceptions were by the Dutch on Java in the mid-19th century and by the Spanish themselves, who established cochineal production plantations on the Canary Islands, also in the 19th century.

The Demand for Scarlet

Secretive about its source and production, the Spanish were very happy to sell the expensive dye to anyone who could afford it. Cochineal's ability to dye cloth a brighter and more lasting red than any other dye was soon appreciated by cloth, silk, and tapestry manufacturers all over the world. The first large markets for the dye included the cloth weavers of the Low Countries and the tapestry makers in northern France and the Netherlands. The silks and velvets produced in Venice using cochineal became famous, replacing the older 'Venetian red', which used local, duller dyes. Cochineal was taken by the Manila galleons from Mexico to the Spanish Philippines and from there to the rest of Asia. China, especially, became a major buyer of cochineal. The colour red had already long been prized for its association with happiness and prosperity, and from the 18th century, this new brighter version was rapidly used for everything from silk clothing to wedding banners. The dye was exported to the Ottoman Empire and so on to the Middle East and Central Asia, finding its way, for example, into Persian carpets. By the end of the 18th century, the whole world was in love with cochineal, and such was its success, there arose widespread confusion as to the real origins of the dye, still Mexico and to a lesser degree South America.

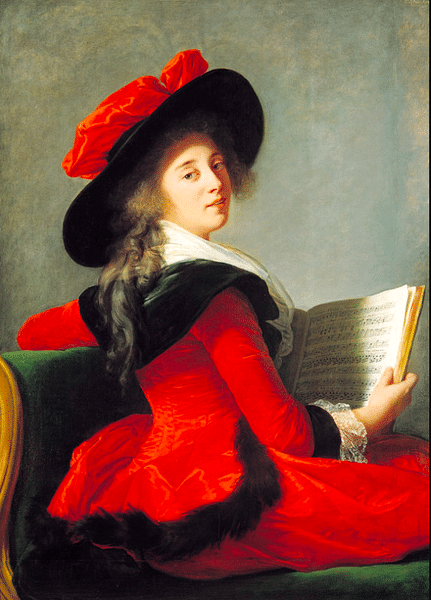

There was another reason for cochineal's success besides its inherent qualities appreciated by cloth-makers. Red became the very height of fashion. Tyrian purple (aka royal purple) had long been the colour of power in Europe thanks to the Roman and Byzantine emperors (and others) whose robes used the dye extracted from the murex shell, but by the 15th century and the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the main supply line of this expensive dye was cut. Cochineal, therefore, found a huge and lucrative gap in the market for luxury goods and garments that symbolised power, prestige, and wealth. Purple was out, and red, scarlet, and crimson were most definitely in. The pope declared that cardinals should wear the colour red. Monarchs and nobles followed suit and began to wear plush red robes. In another example of red symbolising power, authority, and prowess, the famous bright red jackets worn by officers of the British army from the 17th to the 20th century were made using cochineal. So distinctive were these scarlet uniforms, the soldiers were nicknamed the "Red coats". Even in restrictive and highly traditional markets like Japan, cochineal made inroads. The jimbaori, a red jacket decorated with a family crest and worn by high-ranking samurai warriors, was made from cochineal in the 19th century.

Cochineal-dyed materials can also be seen in colonial-era paintings, not only in elite clothing but also in the fashion, for example, of Spanish and Flemish painters to have portrait subjects stand or sit in front of a bright red curtain, a reminder of the wealth required to own such items of decoration. Further, cochineal was used to paint cochineal-dyed subjects. Renaissance artists often called it carmine or lake, and they prized these cochineal-based pigments for their palettes because of their bright and translucent qualities. This esteem for cochineal continued with later artists, notably the impressionists and post-impressionists of the late 19th century.

Into the Modern Era

Cochineal production continued in the post-colonial period in Mexico, Peru, and Argentina amongst other places. Even today, and despite competition from synthetic alternatives since the latter part of the 19th century, up to 200 tons of cochineal are produced each year, mostly in Peru, Mexico, and the Canary Islands. The dye remains a commonly used colouring ingredient of many foodstuffs, particularly beverages (identified as Red E120), and is used in other fields such as medicines, cosmetics, and histology for staining samples on microscope slides. Still today, many artisans around the world prefer the superior properties of cochineal dye for their natural and handmade textiles.