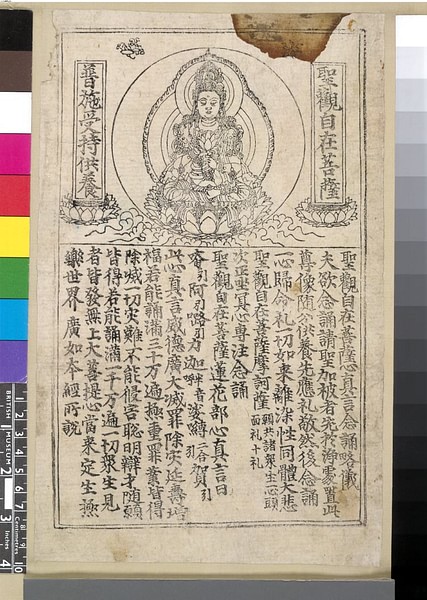

Chinese Literature is among the most imaginative and interesting in the world. The precision of the language results in perfectly realized images whether in poetry or prose and, as with all great literature, the themes are timeless. The Chinese valued literature highly and even had a god of literature named Wen Chang, also known as Wendi, Wen Ti.

Wen Chang kept track of all the writers in China and what they produced to reward to punish them according to how well or poorly they had used their talents. This god was thought to have once been a man named Zhang Ya, a brilliant writer who drowned himself after a disappointment and was deified. He presided not only over written works and writers but over Chinese script itself.

Ancient Chinese script evolved from the practice of divination during the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE). The pictographs made on oracle bones by diviners became the script known as Jiaguwen (c. 1600-1000 BCE) which developed into Dazhuan (c. 1000-700 BCE), Xiaozhuan (700 BCE to present), and Lishu (the so-called "Clerky Script", c. 500 BCE). From these also developed Kaishu, Xingshu, and Caoshu, cursive scripts which writers later used in prose, poetry, and other kinds of artistic works.

Exactly when writing was first used in China is not known since most writing would have been done on perishable materials like wood, bamboo, or silk. Scholar Patricia Buckley Ebrey writes, "In China, as elsewhere, writing, once adopted has profound effects on social and cultural processes (26)." The bureaucracy of China came to rely on written records but eventually writing was used for self-expression to create some of the greatest literature in the world. Paper was invented in c. 105 BCE during the Han Dynasty(202 BCE to 220 CE), and the process of woodblock printing developed during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), and by that time China had already developed an impressive body of literary works.

Early Stories

The earliest written works in China are ghost stories and myths. Ebrey writes how early Han literature is "rich in references to spirits, portents, myths, the strange and powerful, the death-defying and the dazzling (71)". The Chinese were especially concerned with ghosts because the appearance of someone who had died meant that the living had somehow failed them, usually by improper honor in burial, and the dead would haunt the living until the wrong was righted. If the dead could not find their family, they would find anyone nearby.

One famous story is about five brothers who are visited by the ghost of a little girl. They cannot get rid of the ghost until they finally seal her in a hollow log, cap both ends, and throw it into the river. The ghost thanks them for giving her a proper burial and sails away. In another story, the ghost of a mother whose grave was defiled returns to tell her son and ask him to avenge her dishonor. The son does not question the vision for a moment and reports the event to the authorities, who apprehend the criminals and execute them. Ghost stories served to emphasize important cultural values such as the proper treatment of the dead and honoring one's fellow citizens.

A story which exemplifies this is a famous tale concerning a man named Commandant Yang. Yang had lived selfishly and caused great harm to many people without much thought. When he died and went to the afterlife he found himself in front of a tribunal. He was asked by the king of the underworld how he managed to have so many sins built up on his soul. Yang maintained his innocence and said he had done nothing wrong.

The king of the underworld commanded that scrolls be brought in and read. As Yang stood in judgment, a clerk read the date and time of his sins, who was affected by his actions, and how many died because of his decisions. Yang was condemned, and a giant hand appeared and crushed him into a bloody pulp.

In another tale, a man named Coffin Head Li is a bully who preys on cats and dogs. One day he is visited by two men dressed in dark purple robes. They tell him he has been condemned in the afterlife for his abuse of animals. Coffin Head Li refuses to believe them and asks who put them up to this joke. They tell him that they are ghosts, sent from the afterlife, and then produce an official document in which the souls of 460 cats and dogs have registered complaints against him for their abuse and death. Coffin Head Li is condemned and taken away. The abuse of living things, whether people or animals, was considered a grave sin against the community, and ghost stories about immoral acts by people such as Commandant Yang and Coffin Head Li served as cautionary tales of what happened to people who behaved badly.

Ghost stories were accompanied by myths about the Kunlun Mountains where the gods and great men of the past lived. These myths also expressed cultural values and impressed their lessons on audiences. One early myth concerns the demi-god Gun who tried to stop the great flood during the Xia Dynasty (c. 2070-1600 BCE). Gun fails and either kills himself or is exiled and the emperor appoints his son Yu to complete the job.

Yu understands that his father failed because he tried to do too much by himself without asking others for help, refused to respect the forces of nature, and had overestimated his own abilities. Yu learned from his father's mistakes and invited everyone to help him control the flood. By encouraging his neighbors' participation, and respecting their abilities and the power of nature, he succeeded and became known as Yu the Great who founded the Xia Dynasty and established the order of rule.

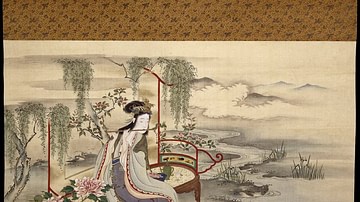

During the Han Dynasty, a very popular myth was the Queen Mother of the West. Ebrey writes:

Her paradise was portrayed as a land of marvels where trees of deathlessness grew and rivers of immortality flowed. Mythical birds and beasts were her constant companions, including the three-legged crow, the dancing toad, the nine-tailed fox, and the elixir-producing rabbit. (71)

The myth became so popular it grew into a cult, which forced the Han administration to commission shrines to the Queen Mother of the West and to acknowledge her worship as a legitimate faith. The popularity of the myth came from its promise of eternal life if one accepted the Queen Mother of the West into their hearts. Followers wore talismans representing her on strings around their necks and carried texts of the story. Ebrey writes, "This movement was the first recorded messianic, millenarian movement in Chinese history. It coincided with prophecies foretelling the end of the dynasty (73)."

In this time of uncertainty, the people latched onto a myth that upheld important values of the past; in this case, that value was permanence. The Han Dynasty might fall but, through faith in the Queen Mother of the West, the individual could continue to live eternally. The texts concerning her, which appear to have been very popular and widely circulated, were mainly hand-written in the Han Dynasty and afterwards. During the Tang Dynasty, though, a process became popular which would make written texts even more accessible to people and help preserve the cultural heritage of the country.

Woodblock Printing & Books

The Chinese produced poetry, literature, drama, histories, personal essays, and every other kind of writing imaginable all of which was done by hand and then copied. The creation of woodblock printing, which became widespread during the Tang Dynasty under the second emperor Taizong (r. 626-649 CE), made books more available to people. Before the invention of woodblock printing, any text had to be copied by hand; this process took a long time, and the copies were very expensive. Woodblock printing was a kind of printing press whereby a text could be copied quickly and easily by carving the characters in relief on wooden blocks which were then inked and pressed to paper.

This method allowed writers to reach a wider audience than they had previously. Even though the technology of woodblock printing had been known since the Qin Dynasty, it had not been used to any great extent. During the Tang Dynasty, poets like the great Wang Wei (l. c. 701-761 CE) were read and appreciated by people who would have never heard of his work before. Scholar Harold M. Tanner writes, "Wang Wei was not only a poet but also an accomplished painter. Some said that his paintings entered his poetry and his poems were suffused with the images of his paintings (189)." Most poets were also painters and Wang Wei's contemporaries created their own masterpieces equal to or greater than his.

In the past, poets like Wang Wei were only read by the elite who could afford the books but, after woodblock printing became more commonplace, anyone with a little disposable income could buy a book. Those who did not have the money could find books at the library. This practice led to a dramatic increase in literacy in China and authors, essayists, historians, scientists, medical professionals, poets, philosophers, and every other kind of writer found they could reach wider and wider audiences with their work.

Literary Works

Chinese literary works are too numerous to list here, spanning some 2,000 years, but among the most influential are those of the Tang Dynasty. The greatest poet of the Tang Dynasty is Li Po (also known as Li Bai, l. 701-762 CE) whose work was so popular in his time that it was considered one of the Three Wonders of the World (along with Pei Min's ability with a sword and Zhang Xu's beautiful calligraphy). Thanks to the woodblock printing process, his work was widely distributed throughout China and over 1,000 of his poems have survived to the present day.

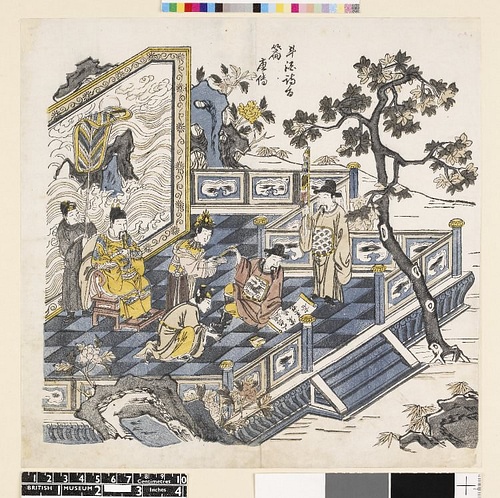

His close friend, Du Fu (also known as Tu Fu, l. 712-770 CE), was equally popular, and the two are regarded as the most important poets of the Tang Dynasty followed by Bai Juyi (also known as Bo Juyi, l. 772-846 CE). Bai Juyi's poem "Song of Everlasting Sorrow", is a romanticized version of the tragic love affair of emperor Xuanzong (r. 712-756 CE) and Lady Yang. It became so popular that it entered the public school curriculum and students had to memorize it in part or in full to pass exams. This poem is still required reading in Chinese schools in the present day.

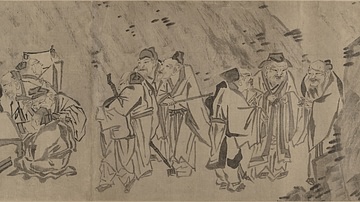

Older works of philosophers such as Confucius, Mo Ti, Mencius, Lao-Tzu, Teng Shih, and others from the Hundred Schools of Thought were also widely available from the Tang Dynasty onward. The most important of these philosophical writings, as far as Chinese culture is concerned, are the texts known as The Five Classics and The Four Books (The I-Ching, The Classics of Poetry, The Classics of Rites, The Classics of History, The Spring and Autumn Annals, The Analects of Confucius, The Works of Mencius, The Doctrine of the Mean, and The Great Book of Learning). Although these works are not 'literature' in an artistic sense, they were central to Chinese education and remain just as important in China today as they were in the past.

These nine works provided a cultural standard that people were expected to meet if they wanted to work for the government, and ensured a candidate was literate and qualified as one of the elite. On an aesthetic level, though, they were considered personally enriching and were read for self-improvement and simple enjoyment. The philosophers and poets of China created many important artistic works, which are still admired today and which contributed to and complemented the works of literary prose which were also produced.

The greatest prose master of the Tang was Han Yu (l. 768-824 CE), considered 'the Shakespeare of China', whose style influenced every writer who came after him. Han Yu is known as an essayist who advocated Confucian values and so is also regarded highly as a philosophical writer. Shen Kuo (l. 1031-1095 CE) was a polymath of the Sung Dynasty (960-1234 CE), whose writings on scientific subjects were extremely influential. Between the 14th and 18th centuries CE, literary fiction reached its heights through the Four Great Classic Novels of China: Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong (l. 1280-1360 CE), Water Margin by Shi Nai'an (l. 1296-1372 CE), Journey to the West by Wu Cheng'en (l. 1500-1582 CE), and Dream of Red Mansions by Cao Xueqin (1715-1764 CE). Of these four, Dream of Red Mansions is considered the greatest literary masterpiece in Chinese writing because of its style, theme, and scope. It was published in 1791 CE and has remained a best-seller in China ever since.

Legacy

These works were read throughout China and those who could not read themselves would hear them read. Chinese script was adopted by Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, and became the basis for Khitan Script (Mongolia), Jurchen Script (of the Manchus), and the Yi Script of the indigenous people of Yunnan Province which differs from traditional Chinese script. Chinese literary works, along with The Five Classics and The Five Books, became the basis for the development of all these scripts and so Chinese thought significantly impacted these cultures. Books like Dream of Red Mansions or Romance of the Three Kingdoms became as popular in other cultures as they were in China and influenced themes of those cultures' literary works.

Scholar Harold M. Tanner writes how, through Chinese literature, especially poetry, we are invited into the world of the writer and experience life directly as "we read their descriptions of home and family, landscapes, palaces, and war, and as they speak out on behalf of the poor and the oppressed (187)". Ancient Chinese literary works are just as moving and impressive today as when they were written because, like any great literature, they tell us what we need to know about ourselves and the world we live in. Through their work, the great Chinese masters wrote about their personal experiences in life and, in doing so, gave expression to the whole human experience.