Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1725) was a Japanese playwright who wrote for both the puppet theatre and kabuki. He is regarded as Japan’s greatest dramatist. Apart from their aesthetic appeal, his plays are of value because they provide an insight into Japanese society in the Edo period (1603-1868).

The Social Setting

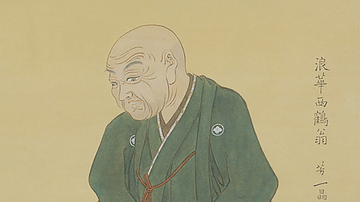

In the early Edo period, Japanese society changed a lot. The settled conditions following the establishment of Tokugawa rule led to the expansion of agriculture, rapid population growth and increased urbanisation at both the local and national level. Before 1600, Kyoto was the only large city in Japan. It was the capital and the home of both the imperial family and aristocratic cultural traditions. In the 17th century two new cities developed. In eastern Japan, Edo (modern-day Tokyo) served as the seat of government for the Tokugawa family and, as a political centre, it had a high warrior population. In western Japan, Osaka developed as a major commercial hub with a large merchant class. In the late 17th century, a new urban culture appeared in these three cities and this was reflected in the novels of Ihara Saikaku, the poetry of Matsuo Basho, and the plays of Chikamatsu Monzaemon. This cultural flowering is usually referred to as ‘Genroku culture’, although the Genroku period itself only lasted from 1688 to 1704. It largely coincided with the life and reign of the shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (1646-1709).

This was a time of rapidly changing values. At the beginning of the Edo period, the Tokugawa established a hereditary, hierarchical class system with warriors at the top followed by farmers, artisans, and merchants. Warriors, whose function had suddenly changed from one of fighters to one of civil administrators, were at the top because they were the ruling class. Farmers were second because they produced food and artisans were third because they made useful things. Merchants were at the bottom because, it was argued, they did not make anything themselves and just lived off what others produced. As a commercial economy developed, however, the merchants tended to get richer and the warriors, who lived on fixed stipends, got poorer.

The newly rich merchant class found entertainment in what in English are called ‘pleasure quarters’. These were areas where the government allowed the establishment of large numbers of brothels. The best-known of these were the Yoshiwara area in Edo, the Shimbara area in Kyoto, and the Shinmachi area in Osaka. This was referred to as the ‘ukiyo’ or the ‘floating world’. This was originally a Buddhist term that referred to the transient nature of human life but it came to be used to mean the transient nature of pleasure. The government imposed regulations on these areas not out of any sense of morality but out of a desire to restrict disruptive social behaviour. The women who worked as prostitutes largely did so because of poverty but in Japan at the time, sex did not have the kind of shameful or sinful connotations it had in countries influenced by Christianity. These pleasure quarters exercised a kind of cultural influence in Edo period Japan much as Hollywood did in 20th century America. The courtesans who worked there, and their customers, figure prominently in the literature and theatre of the Edo period.

The Development of Puppet Theatre & Kabuki

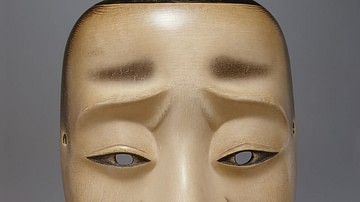

Before the Edo period, the main form of theatre in Japan was the aristocratic Noh drama. There were also more popular forms of entertainment and it was out of these that both the puppet theatre and kabuki developed.

In the European tradition, puppets are thought of as being entertainment for children but this was not the case in Japan. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, puppet theatre developed as a sophisticated art form. In modern Japanese this is called ‘bunraku’, a term derived from the Uemura Bunrakuken theatre troupe that operated the Bunraku-za theatre in Osaka in the second half of the 18th century. Historically, however, it was called ‘joruri’ or ‘ningryo joruri’. It developed out of an older oral tradition in which wandering minstrels recited stories about heroic warriors of the past. Stories about Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-89) and his beautiful lover, Lady Joruri, were especially popular. These stories would be accompanied by music played on a lute-like instrument called a biwa. In the 16th century, the biwa was replaced by the shamisen, a three-stringed instrument with a very different tone. In the early 17th century puppets (‘ningyo’ in Japanese) were added giving it its final form: puppets, music, and recitation. Of these, the recitation was considered the most important.

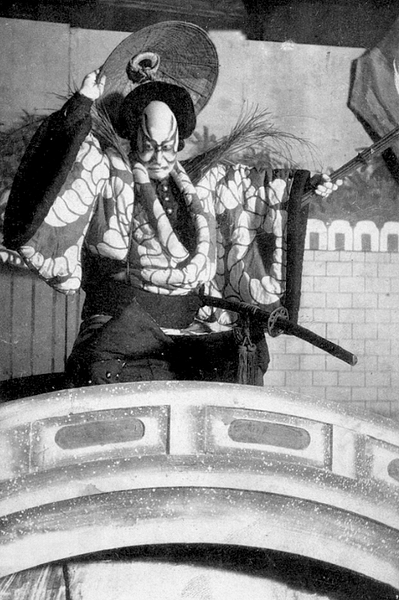

In contrast to the puppet theatre, kabuki developed from a dance tradition and the actor’s physical performance was always the focus of attention. Kabuki performances were flamboyant with actors wearing brightly coloured costumes, makeup and using exaggerated movements to enhance the story. Kabuki had an erotic aspect and overt connections with both male and female prostitution. In the mid-17th century, the government restricted performances to adult males in order to help maintain social order. This pushed kabuki to develop as an art form but it continued to have close connections with the ‘pleasure quarters’.

Chikamatsu’s Early Years

Chikamatsu, whose real name was Sugimori Nobumori, was born into an upper-class warrior family in Echizen Province (modern-day Fukui Prefecture) in 1653. His grandfather served the daimyo of Echizen as a medical doctor. At some point, his father lost his warrior status and the family moved to Kyoto. Chikamatsu served in several courtier families where he was exposed to aristocratic culture, especially the tradition of court poetry. In his twenties, he began working for Uji Kaganojo (1635-1711), the foremost puppet reciter in Kyoto. The first play known to have been written by Chikamatsu was Yotsugi Soga ('The Soga Successor'), which was performed in 1683. It was a great success and it established his reputation as a playwright. He became the first professional playwright in Japan as, unlike his predecessors, he never performed in any of his plays. In 1684, Takemoto Gidayu, a reciter who had also worked for Kaganojo in Kyoto, decided to establish his own theatre in Osaka, and in the following year, Chikamatsu began writing for him. Takemoto developed a style of recitation so distinctive and influential that all subsequent joruri recitation came to be called ‘gidayu’.

In addition to writing for Takemoto, Chikamatsu also wrote for the kabuki theatre. He had an especially strong connection with the actor Sakata Tojuro (1647-1709). Although he wrote his last kabuki play in 1705, his experience in that genre impacted on his puppet plays and it is for these that he is mainly remembered today.

The puppet plays can be divided into two genres:

- ‘historical dramas’ (jidaimono)

- ‘contemporary life dramas’ (sewamono).

The Historical Dramas

His historical dramas drew heavily on pre-Tokugawa Japanese war tales for material. He wrote 12 plays based on the Soga Monogatari ('The Tale of the Soga Brothers'), nine based on the Heike Monogatari ('The Tale of the Heike'), seven based on the Giheiki ('Tale of Yoshitsune'), five on the Taiheiki ('Record of the Great Peace') and five about the historical figure Yoritomo no Yorimitsu. Chikamatsu’s approach to retelling these stories, however, was extremely innovative.

His first play, The Soga Successor, for example, was based on the Soga Monogatari but it was reimagined in such a way that it amounted to a completely new story. In the original Soga Monogatari, the heroes are the two Soga brothers who spent 17 years getting revenge on the person they hold responsible for the death of their father. In The Soga Successor, however, the Soga brothers are only peripheral characters and the heroes are two of their loyal servants. The servants carry out a task comparable with the vendetta in the original story. In the second act, their lovers, Tora and Shosho, make an appearance and they represent a new kind of female character. They are portrayed as the kind of courtesans that could be found in a contemporary Edo-period brothel. They are just as virtuous as the women who appear in the original Soga Monogatari, but they are beautiful and talented entertainers who sing and dance while also being loyal, intelligent, resourceful, and compassionate. Thanks in part to Chikamatsu, ‘courtesans in love’ became the new secular model of feminine virtue for the urban class.

In addition to updating stories and characters, Chikamatsu also experimented with portraying current events in the guise of historical dramas. The best example of this is Goban Taiheiki ('Chronicle of Great Peace Played on a Go Board', 1710). In 1703, 47 warriors from Ako domain carried out a revenge attack on the man they regarded as responsible for the death of their lord. They were subsequently arrested and the government ordered them to commit seppuku (ritual suicide) as punishment. The Ako Incident, as it was called, was a sensational event at the time. Chikamatsu had written many popular plays about vendettas so it was naturally the kind of thing that would catch his eye. As the government banned the theatrical portrayal of politically sensitive topics, he retold part of the story in a play but set it back in the 14th century CE to avoid censorship. He drew on an episode in the Taiheiki for the basis of his play but changed the names of the participants so that they closely resembled those in the actual Ako Incident. He also added new fictitious elements to the story. In the play, one of the participants in the planned revenge attack, as he is dying, draws a map of their target’s mansion with the black and white stones and the board used in the game of go. This scene gave the play its name. The practice of setting the Ako Incident story back in the world of the Taiheiki was taken up by later playwrights. This was most famously done in 1748 in the play Chushingura, which went on to become the most popular play in the history of Japanese theatre. The practice of setting plays in a particular historical ‘world’ (sekai) also became a theatrical convention taken up by later playwrights.

Chikamatsu’s most famous historical play was Kikusenya Kassen ('The Battles of Coxinga', 1715). It was based on the attempts by the Chinese general Zheng Chenggong (1624-66) to restore the Ming dynasty in China. Even though it is a ‘historical play’, the events it portrays are much more recent than in Chikamatsu’s other historical plays. The reason for its popularity can be ascribed to its exotic location and spectacular effects well suited to the puppet theatre. One character, for example, plucks out his own eye while another gives birth via a caesarean section. Through a comparison with Ming China, the play also implies some criticism of corruption within the Tokugawa government.

The Contemporary Life Dramas

Although historical dramas account for about three-quarters of Chikamatsu’s puppet plays, he is best remembered today for his contemporary life dramas. As the name suggests, these were plays that portrayed contemporary events.

One of the most successful of these was Sonezaki shinju ('The Love Suicides at Sonezaki') first performed in 1703. This was based on a real event that had occurred in Osaka about two weeks before the play opened. In this story, Tokubei loves a courtesan called Ohatsu but his uncle, for whom he works, wants him to marry his wife’s niece. He refuses but his stepmother accepts a dowry from the uncle. Tokubei is unaware of this and when he continues to refuse to marry the niece, the uncle gets angry, fires him and demands the dowry back. Tokubei manages to get the money back but his friend Kuheiji says he needs to borrow it to avoid bankruptcy. He lends him the money but when it comes time for it to be repaid, Kuheiji denies having received it. Tokubei realises he has been tricked. Later he goes to the teahouse where Ohatsu works and there he hears Kuheiji spreading the false story about him. Tokubei expresses his desire to die to Ohatsu and she agrees to die with him. That night the two travel together to Sonezaki Shrine where Tokubei binds Ohatsu to a tree before stabbing her, and himself, to death.

This brief summary does not do justice to the intricacies of the story or the aesthetics of the play but, from it, you can see that it is a tale about ordinary people and the kind of trials and tribulations they encounter in their everyday lives. Unlike the historical dramas, which often had fantastic plot lines and effects, the contemporary life dramas were quite realistic. The play, which also incorporated new theatrical devices, was extremely popular and it restored the financial viability of the Takemoto Theatre at a time when it had been faltering. Chikamatsu wrote many more ‘love-suicide’ dramas including Shinjū Ten no Amijima ('Love Suicides at Amijima', 1715), which is regarded as being one of his best works. These plays were so popular that in 1723 the government banned more plays on the topic in order to discourage real couples from taking their own lives in imitation of those on the stage.

After Chikamatsu’s death in 1725, his plays quickly went out of fashion and were not often performed, especially in their entirety. This was largely because of changes in the puppet theatre, especially the introduction of puppets manipulated by three people instead of just one, and so made his plays old-fashioned at a time when the genre was entering its golden age. Despite this, the innovations he introduced played a critical role in the development, not just of the puppet theatre, but the Japanese theatrical tradition in general.

![[Kokusenya Kassen.] The Battles of Coxinga. Chikamatsu's Puppet Play, Its Background and Importance. By [i.e. Translated and Edited by] Donald Keene, Etc](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41sw2lVuIgL._SL160_.jpg)