A unique and fundamental aspect of ancient Judean society in both Israel and the Diaspora, the ancient synagogue represents an inclusive, localized form of worship that did not crystallize until the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. In antiquity, there was a variety of terms that represented the structure, although some of these were not exclusive to the synagogue and may refer to something else, such as a temple. These terms include proseuchē, meaning "prayer house" or "prayer hall"; synagoge, meaning "a gathering place"; hagios topos, meaning "holy place"; qahal, meaning "assembly"; and bet kneset or bet ha-kneset, meaning "the house of gathering". The oldest term, proseuchē, originated in 3rd century BCE Hellenistic Egypt and clearly identifies a key characteristic of the structure: prayer. Although Torah reading set the synagogue apart from other public buildings or places of worship, much like the Temple before it, the Torah was not the only defining feature of the synagogue. Other distinctive traits included the activities that took place within them as well as the art and architecture of the structures themselves.

The Role of the Ancient Synagogue

Inscriptional and literary evidence suggests that judicial proceedings, archives, treasuries, prayers, public fasts, communal meals, and lodging for traveling Judeans were all associated with the ancient synagogue. The public reading and teaching of the Torah took precedence over all else by providing the liturgical activity that set the synagogue apart, but the synagogue was much more than a religious institution and must be considered as distinctly different from its predecessor, the Temple.

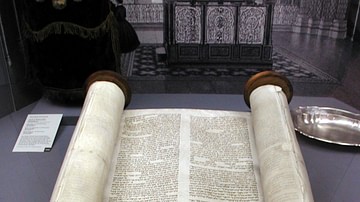

Following the destruction of the Second Temple and the rise of Rabbinic Judaism, a more democratic form of worship began to take root, as well as concepts such as urbanization and institutionalization, which spread throughout the Roman, and later Byzantine, Empire. With the end of the Second Temple period came the end of the practice of sacrifice, and so the reading of the Torah filled the void. As a result, the Ark of Scrolls and the Torah shrine developed, eventually emerging as the focal point of the synagogue, representing a symbol of survival and preservation. Nearly every ancient synagogue in the land of Israel yields traces and fragments of a Torah shrine, either in the form of a raised platform as a base for the aedicula, a niche, or an apse. This evidence demonstrates the significance of the Torah shrine as one of the few consistent features within the ancient synagogue. Yet the appearance of the Torah shrine was not the only emergent trait accompanying the rise of Rabbinic Judaism. Unlike the exclusivity of priestly-mediated ritual attributed to the Temple, the participants in the ancient synagogue were involved in the performance and conducting of ceremonies, reciting prayers, and reading from the Torah. A new participatory nature of worship was developing during this period, and it is preserved through the architectural remains.

As the rabbinic class rose in power, criteria that may be deemed "non-religious" began to fall under the control of the rabbis, and therefore, the "religious" domain. In terms of legal matters, Tannaitic cases may relate to settlements for divorce/widowhood, damages for public shaming, deeds dating on the Sabbath, and so on. Despite the fact that other venues were available for resolving legal matters, the rabbinic judges served as an alternate, and seemingly popular, venue. Generally, rabbinic legal activity revolved around property and family issues, which occasionally intersected with ritual law such as in Deut. 5-10 and halîsâ, a ceremony concerning the obligation of a man to marry his brother's childless widow. Quite simply, aside from the reading and studying of the Torah, the separation of religious and non-religious functions is not as clear as one may assume in terms of the activities performed in the ancient synagogue. Whether separate or not, both religious and non-religious activities attributed to the synagogue originated in response to communal requirements, differing in distribution throughout the ancient world with the exception of the study of the Torah, around which the synagogue's ultimate purpose revolved.

As a result of the Torah's dominance in synagogue performance, it seems only reasonable that it would become a popular motif with the rise of Jewish art in late antiquity, and in fact, the Torah Ark would become just that. Yet the Torah's dominance would be expressed by other means as well, such as with the development of the Torah shrine as the focal point and physical statement of Judean religious and historical lineage. Beyond the Torah shrine, however, the ancient synagogue would come to develop additional features and characteristics that reflected communal needs and practices, all of which are evident in archaeological remains.

The Form & Structure of the Ancient Synagogue

Unlike the Temple or the Tabernacle, a synagogue could be established anywhere, as it is not believed that the synagogue was ordained by Yahweh/God. Yet sources, such as the Sages, do suggest a level of holiness in the synagogue when stressing the importance of scripture, and the appearance of the Tabernacle in synagogal art may represent a “seal of approval” or sanctity as well. It is important to remember, however, that although the synagogue represented much more to the community than a place of worship or prayer, it was only deemed “holy” or “sacred” with the presence of the Torah.

As synagogues were not restricted to a specific location, and as no uniform design or floor plan of the ancient synagogue exists, the community was at liberty to build the structures in accordance to their own local requirements. They may be located on the seashore, along riverbanks, in the center of town, or in dwelling quarters. The only common feature to be found in terms of location is convenience for the community for both commercial and communal activities.

The synagogue should be understood as a physical mediator between the individual and the community at large. As a public space, the synagogue became a focal point in Judaism, much like the Temple pre-70 CE. As a structure, the ancient synagogue may have consisted of a single public building or a complex including rooms and courtyards, and the layout of each building varied. The evidence of extra rooms, as well as fountains, cisterns, and basins, demonstrates several characteristics of the local Judean community in which the building was established. Once again, local demands influenced the design and function of the synagogue within each individual community, and it is through the examination of the remains that particular communal requirements may be discerned. For instance, the presence of extra rooms suggests various possibilities. The first possibility indicates lodgings or hostel services in which the synagogue offered temporary accommodations for travellers, pilgrims, or synagogue officials. The appearance of extra rooms may also point toward the existence of a dining room, school, ritual baths (miqva'ot), or additional space for circumstances such as the New Moon or the Sabbath.

Without a universal floor plan, it is clear that each community valued and required different architectural or functional features, and the design of a synagogue was decided upon by the leaders of the community rather than according to an established synagogue standard. That being said, however, as the Torah shrine was located along the Jerusalem-oriented wall within each synagogue in antiquity, it is reasonable to suggest that a Judean travelling from Ostia to Ein Gedi would feel comfortable within the foreign synagogue, so far as the fundamental characteristic, namely the Torah, was concerned.

The Ancient Synagogue in the Diaspora

Much attention has been placed on the synagogues of ancient Israel thus far, however, many of the same conclusions may be made in terms of the Diaspora synagogue. Individuals living within the Diaspora experienced a disconnection from the Temple in a period much earlier than 70 CE. As a result, accommodations and supplementary modes of worship developed for those who were unable to make the pilgrimage to the Temple. Unfortunately, the synagogues in Delos and Ostia are the only locations that can be archaeologically dated prior to the 2nd century CE; however, it is probable that synagogue architecture had not yet developed to a distinguishable level until that time. Considering that several Diaspora synagogues began as domestic structures, only later acquiring monumental characteristics, this theory is especially persuasive.

The function and style of the Diaspora synagogue were not unlike the synagogue of ancient Israel. Like their counterparts in Israel, Diaspora synagogues display some variation in terms of style and artistic content, yet a common and shared tradition appears to have influenced Judeans everywhere. There is little consistency in terms of location, yet this inconsistency is a trend that is shared by both synagogues in Israel and those in the Diaspora. The only quality that the locations share is the convenience they provided to the community, both commercial and communal. Aside from that, the location may represent the prominence and social acceptance of the local Jewish community, especially in the Diaspora. For instance, in a metropolitan city such as Alexandria, if a synagogue were discovered in the city center or along the central street, this would suggest a high level of acceptance by the general population for the Judean community. The prominence of the community would also be reflected in the existence of the synagogue, both in design and maintenance, as it would require great expense by the Judean community itself. Interestingly enough, inscriptions suggest that it was not only Judeans but also non-Judeans who made donations to the synagogue, perhaps in fulfillment of a vow. Under certain circumstances, some Christians even preferred to attend synagogue services rather than those of their own churches, as was the case in Antioch.

Location and the sheer existence of the synagogue aside, the orientation of the interior demonstrates a universal expression of loyalty, as each synagogue in antiquity was oriented towards Jerusalem. This suggests a preservation of the memory of the Temple as well as the history of the Judeans more generally. With each synagogue oriented towards Jerusalem, the community was reminded of the Temple as well as its destruction. The Jerusalem-oriented wall became a memorial that was repeated everywhere. It was along this wall that the Torah shrine was located, and despite the variations in style, including aedicula, niche, or apse form, the Torah shrine was the focal point of each synagogue, marking a change in significance for the institution following 70 CE by instilling a sacred or holy quality.

Aside from the presence of the Torah, there was one other feature that was widely spread in both Israel and Diaspora synagogues: purity concerns. Just as they - alongside sacrifice - dominated Temple Judaism, purity concerns persisted and were reflected in synagogue architecture. Whether they were incorporated into the design in the form of a fountain or basin, or the synagogue was merely located near a body of water, the necessity for water facilities was widely established in both Israel and the Diaspora. Despite the limited remains of miqva'ot near Diaspora synagogues, they were occasionally present in ancient Israel, perhaps as a lingering Temple tradition. Fountains, cisterns, or basins, on the other hand, were often located in the courtyard or entranceway of the Diaspora synagogue, suggesting a similar function to the miqva'ot, complementing the Mishnah and Tohorot, a post-70 CE construction expressing laws of purity, cleanliness, and uncleanliness. The existence of such concerns suggests that the synagogue represented more than a community center, while the inclusion of additional rooms and supportive inscriptional evidence indicates that the synagogue was more than a religious institution. The fact that this evidence is spread throughout the ancient Judean world, both within Israel and the Diaspora, demonstrates the expansive and diverse expressions of Judean identity in response to local influences and traditions.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the synagogue grew in popularity following the destruction of the Temple, allowing prayer and study to replace sacrificial practices as the means of serving God. Unlike the Temple, participation in the synagogue was open to the congregation members who were invited by the synagogue leaders to read scripture and even preach. Although the reading of the Torah became the prominent feature of the synagogue as is reflected through the universal inclusion of the Torah shrine in archaeological remains, the synagogue represented much more than a house of prayer. It was also an institution for teaching, lodging, communal meals, public fasts, judicial proceedings, public floggings, eulogies, nuptial matches, and so on. Essentially, the synagogue represented an ancient community centre, an institution that developed in various Judean communities throughout the ancient world in response to local social needs and preferences. As a result, the synagogue developed in the form of an assembly hall, and although architectural designs may vary, characteristic features such as the Torah shrine assist in identifying them within the archaeological record. Furthermore, the variety of architectural designs revealed that the existence of uniform worship did not require a uniform space.