The Battle of Guilford Court House (15 March 1781) was one of the last major engagements of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Fought near Greensboro, North Carolina, it was a pyrrhic victory for the British army under Lord Charles Cornwallis, which narrowly defeated Major General Nathanael Greene and the Southern Continental Army at the cost of 25% casualties.

The American South, at the time, had been the target of British invasion for a little over two years. Beginning with their capture of Savannah, Georgia, in December 1778, the British focused their military strategy almost entirely on the South, the capture of which would deny the United States access to the region's wealth generated from the sale of cash crops such as indigo, rice, and tobacco. Additionally, the South was rumored to be replete with Loyalists who were expected to welcome the British army with open arms. After the capture of Georgia, the British implemented the next step of their 'southern strategy' and occupied Charleston, South Carolina, in May 1780. However, despite the best efforts of Lord Cornwallis, the state proved much more difficult to subdue than anticipated. Fewer Loyalists rallied to British banners than expected, while many Patriot militias sprung up in the South Carolina backcountry to resist British occupation. These militias proved to be a thorn in Cornwallis' side, disrupting enemy operations and skirmishing with British and Loyalist detachments. Patriot militias even won a major engagement against a party of Loyalists at the Battle of Kings Mountain (7 October 1780).

The success of these militias encouraged General Greene, who had been sent by George Washington to take command of the ragged Southern Department of the Continental Army at Charlotte, North Carolina. While Greene set about whipping this army into shape, he dispatched Brigadier General Daniel Morgan into South Carolina with 600 men to aid the Patriot militias in the region. Morgan exceeded expectations when he defeated a British detachment under Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens (17 January 1781), which caused South Carolina to slip further from Cornwallis' grip. Looking to avenge the defeat, Cornwallis marched into North Carolina to pursue Greene and Morgan, leading to the fight at Guilford Court House. Although Cornwallis won this engagement, he was unable to decisively defeat Greene's army; with his supply line stretched dangerously thin, Cornwallis decided to abandon the Carolinas altogether and march into Virginia, where he would ultimately meet defeat at the Siege of Yorktown. Therefore, although Guilford Court House was tactically an American defeat, it helped set the stage for the final American victory at Yorktown.

Cornwallis Vows Revenge

On 18 January 1781, Lord Charles Cornwallis planted his sword in the ground, pensively leaning on it as he listened to his subordinate, Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton, explain how he had lost his detachment at the Battle of Cowpens the day before. With his eyes downcast, the young colonel explained how he had chased Daniel Morgan's small army to the meadow of Hannah's Cowpens, where he had found them sitting out in the open, flanks exposed and backs to the Broad River. Sensing an easy victory, Tarleton had ordered his men to charge, little knowing that they were walking into a trap. Morgan's first two lines of defense, consisting of skirmishers and militia, offered some resistance before feigning retreat, luring the British troops inward. As the British exchanged volleys with Morgan's third line of experienced Continentals (regular soldiers), the militia rejoined the battle and struck Tarleton's left flank, just as the American cavalry attacked the British right flank and rear. Caught in a double envelopment, the British threw down their arms; 100 had been killed, with over 800 taken prisoner. Tarleton himself had barely managed to escape.

Cornwallis listened to this report in sullen silence, absent-mindedly putting more of his weight onto the sword as his anger grew. Finally, the sword snapped in half, sending the British general into a rage. Throwing the broken hilt to the ground, Cornwallis demanded vengeance and prepared to go after Morgan and Greene. He marched his army to Ramsour's Mill where he paused to destroy his baggage train. Tents, furniture, wagons, and even his officers' extra uniforms were thrown onto a bonfire and burned, to allow the army to travel faster. On 28 January, Cornwallis ordered each soldier to be given an extra gill of rum before setting out once again, marching for Morgan's last known location on the Catawba River. The British reached the river on 1 February, finding it on the verge of overflowing after the recent torrential rains.

Morgan had, meanwhile, crossed the Catawba and entered North Carolina, looking to rendezvous with General Greene and the main army at Salisbury. Morgan left behind 300 North Carolina militia under General William Davidson to guard the four passes over the Catawba. When the British began to cross at Cowan's Ford, they came under fire from Davidson's militia. This resulted in a brief skirmish that ended when Davidson was killed by a bullet to the heart, causing his men to disperse. As he waited for his army to complete the crossing, Cornwallis sent Tarleton ahead to chase down the militia. Eager to recover his reputation after Cowpens, Tarleton and his elite dragoons tracked the survivors of Davidson's militia to Torrence's Tavern, where he assaulted their camp and scattered them. Although they were ultimately defeated, the militia put up enough of a fight to allow Morgan's main army to escape from Cornwallis' clutches.

Race to the Dan

On 3 February, Morgan reached the Trading Ford on the Yadkin River, where he was greeted by General Greene. The Yadkin, too, was close to overflowing from the recent rains, but Morgan's men made it across on some boats provided by Polish engineer Tadeusz Kościuszko. Morgan's army had substantially shrunk since entering North Carolina, as many of his militia had deserted and returned to their homes. To make matters worse, Morgan's sciatica had flared up, leaving him confined to a litter. Despite these difficulties, Morgan's withered force reached Guilford Court House on 4 February, where it linked up with Greene's main army. Three days later, Lt. Colonel Henry 'Lighthorse Harry' Lee arrived at the American camp with his legion, raising the number of Greene's troops to just over 2,000 men.

Greene liked the ground around Guilford Court House and wanted to stand his ground and fight. However, his war council, which consisted of 'Lighthorse Harry' Lee, Otho Williams, Isaac Huger, and the ailing Daniel Morgan, did not agree. They told Greene that the army was still too sick and ill-equipped to stand against Cornwallis' 2,000 regular troops; to preserve the army and buy time, the officers urged Greene to continue his retreat toward the border with Virginia. Greene agreed and resumed his retreat, beginning the so-called 'Race to the Dan' as the Continental Army hurried toward the Dan River on the North Carolina-Virginia border, with Cornwallis never far behind. On 13 February, the Patriots safely made it across the river.

Cornwallis did not follow; he was over 200 miles (320 km) away from his supply base at Camden, South Carolina, and did not want to stretch his supply line even further by entering Virginia. Instead, he turned around and occupied Hillsboro, North Carolina. On 20 February, Cornwallis issued a proclamation, inviting all North Carolina Loyalists to take up arms and join his army to help restore royal authority to the Carolinas. Many curious locals came out to catch a glimpse of the British army, going home once they had done so. However, very few North Carolinians arrived to actually join the British. But Greene, sitting on the Virginian side of the Dan River, was not aware that Cornwallis' recruitment drive had failed; he had received false reports that Loyalists were flocking to the British side. Greene felt obligated to return to North Carolina rather than let the state fall to the British and crossed back over the Dan on 23 February, his army bolstered by 600 Virginia militia.

When Cornwallis heard that Greene was back in North Carolina, he moved out of Hillsboro and prepared for a fight. Over the next several weeks, the armies maneuvered around each other, leading to several minor skirmishes between them. The most significant of these skirmishes occurred on 24 February, when a Loyalist militia under Dr. John Pyle was attacked in Alamance County by 'Lighthorse Harry' Lee. Pyle's Loyalists mistook the green-coated dragoons of Lee's Legion for Tarleton's men and therefore did not put up any resistance until Lee's dragoons opened fire. The Loyalists were taken completely by surprise, suffering over 300 casualties before scattering into the woods. The lopsided fight, later referred to as 'Pyle's Massacre', greatly diminished British morale.

Preparations

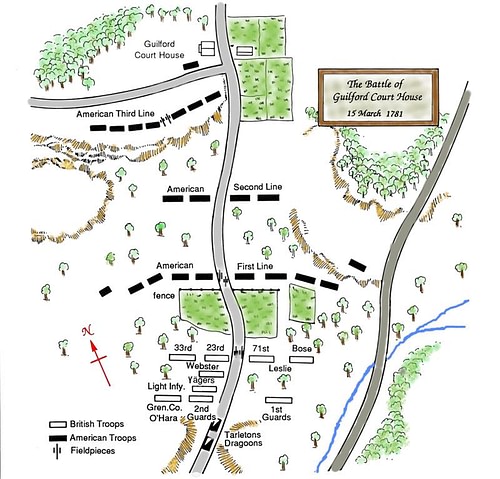

By early March, the strength of Greene's army had greatly increased, as he had been sent an additional 400 Continentals and 1,600 militia from Virginia; he now had roughly 4,500 men under his command, outnumbering Cornwallis' 2,100 troops. But Greene would have to act fast, since most of his militia had signed on to serve for only six weeks. On 14 March, he moved his army back to Guilford Court House, the ground where he had wanted to fight a month before. The courthouse rested on a hill at the edge of a small village, overlooking a densely wooded valley. At the opening of the valley were fields that had been cleared for the cultivation of corn, to the north of which was another patch of woods.

Greene decided to take a page out of Daniel Morgan's playbook and divided his army into three lines of defense. The first line was positioned along a split-rail fence just in front of the cleared fields; 1,000 North Carolina militia were placed in the center, with 300 Continentals to their left and 350 more Virginians from Lee's Legion anchoring their right. Lt. Colonel William Washington's cavalry hung back in support. The second line was positioned roughly 400 yards (365 m) behind the first and was concealed entirely in the woods; this line consisted of two brigades of Virginia militia, a total of 1,200 men, commanded by Edward Stevens and Robert Lawson. Greene's third, and most formidable, line was positioned on the hill in front of the courthouse and consisted of 1,400 Continentals under Isaac Huger and Otho Williams. As at Cowpens, the goal was for each line to wear down the advancing British troops before retiring, so that the British would break upon reaching the third defensive line.

Meanwhile, the British had marched all night to cover the 12 miles (19 km) to Guilford Court House. They were tired and hungry, having eaten nothing since the army ran out of flour the day before. Tarleton's dragoons rode several miles ahead of the main army and, at 10 a.m. on 15 March, encountered Lee's cavalrymen, who had likewise been sent ahead to watch for the British advance. A brief cavalry fight ensued in which Lee's troopers were chased off; Tarleton had taken several prisoners but sustained a wound in the right hand that would cost him two fingers. The rest of the British army entered the valley, and Cornwallis spent the remainder of the morning forming up his troops. On his right flank, Cornwallis positioned his elite Highlanders and most of his Germans under the command of General Alexander Leslie. On the British left were the famous Royal Welch Fusiliers and the 33rd Regiment of Foot, under Lt. Colonel James Webster. General Charles O'Hara, Cornwallis' second-in-command, was held in support along with the grenadiers and German jägers, or riflemen. Tarleton's cavalry was kept in reserve.

The Battle

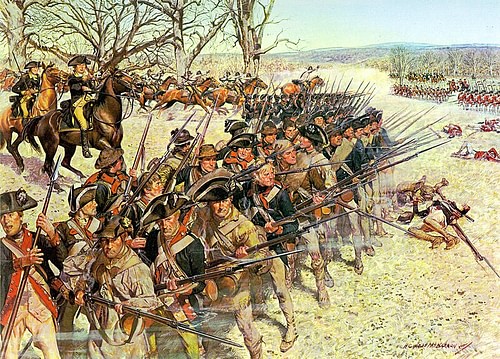

As soon as the British soldiers had appeared in the valley, the American cannons roared to life and were answered by the British artillery; however, neither side managed to inflict much damage. Around 1:30 p.m., Cornwallis ordered his men to begin their advance. Concealed behind their rail fence, the North Carolinians waited until General Leslie's British troops had come within 150 yards (137 m) before unleashing their first musket volley; several British troops went down, causing one eyewitness to liken the British line to "scattering stalks in a wheat field, when the harvest man has passed over it with his cradle" (Middlekauff, 489).

The well-disciplined British soldiers quickened their pace, coming within even closer range of the Americans; the North Carolinians desperately tried to reload as they heard General Leslie order his men to present arms, take aim, and fire. Before the smoke from the British volley even had time to clear, the Highlanders surged forward, bayonets fixed, causing most of the terrified Carolinians to throw down their weapons and run. Lee ordered the militia to stand their ground, even threatening to shoot those who kept running, but the men just streamed past him. On the left-hand side of the battlefield, Colonel Webster also broke through the American line, urging his men onward with the cry, "Come on, my brave Fuzileers!" (Boatner, 464).

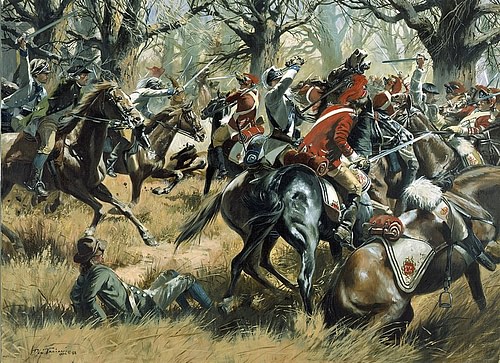

Both halves of the British army advanced for about 400 yards (365 m) until they encountered fierce resistance from the second American line of Virginia militia. On the north side of the battlefield, Leslie's troops charged forward and began fighting with Edward Stevens' brigade, while on the south side, Webster's British troops came up against Robert Lawson's Virginians; this led to confused and scattered fighting throughout the woods, as the British flanks also came under enfilading fire from Lee's men, and from Colonel Washington's cavalry. Eventually, however, Cornwallis sent in General O'Hara's troops in support, and the Americans were slowly pushed back. Cornwallis himself was riding amongst his men shouting encouragement.

After clearing the woods of the Virginians, the British continued their intrepid advance, despite having already suffered a large number of casualties. They approached the third and final American line, made up of experienced Continentals positioned on high ground. Again, the British assaulted the American line and sustained several casualties as they rushed up the slope. The Continentals drove the British back with a bayonet charge of their own; the British almost broke through the American right flank but were driven back by Washington's cavalry. The British wasted no time launching another assault, which quickly devolved into brutal hand-to-hand combat. Watching this mass of humanity engaged in a fight to the death, Lord Cornwallis had an idea; he had two three-pounder cannons brought up and loaded with grapeshot, taking aim at the throngs of struggling troops. General O'Hara, who had been wounded and was lying nearby, begged Cornwallis to reconsider, since firing the cannons would kill men on both sides. Cornwallis refused to listen and ordered the cannons to fire, sending shards of grapeshot shredding into the flesh of American and British troops alike.

The unexpected grapeshot surprised the two sides and caused them to disengage. This worked to the advantage of the British; they had been losing the hand-to-hand fight, but the interruption gave them time to reform and attack again. At this point, Greene realized that there was too much at stake; if his army was destroyed, there would be no one to stop Cornwallis from securing control of the entire South. To save what was left of his army, therefore, Greene gave the order to retreat, abandoning his artillery and wounded on the field. The Americans successfully escaped the battle, as the British were much too tired to pursue.

Aftermath

At the end of the day, Cornwallis maintained control of the battlefield, which, according to the military customs of the time, meant that the British had technically won the battle. But it had been a costly victory, one that Cornwallis could not afford. He had lost 532 men killed and wounded, which amounted to roughly 25% of his entire force; considering how far away he was from the British base at Camden, these losses would be impossible to quickly replace. The Americans also suffered egregious losses, with a total of 79 killed, 185 wounded, and 1,046 missing. However, Greene's army lived to fight another day; as long as it remained in the field, the South would remain unsubdued. Additionally, Greene could more easily replace his losses from local militia and from Continentals sent from Virginia.

After the battle, Cornwallis marched his army to Wilmington, North Carolina, to lick his wounds and assess his situation. His supply line was still stretched dangerously thin, and his absence from South Carolina had emboldened the Patriot militias there even further. Cornwallis believed that, if he remained in the Carolinas, he would never be done playing whack-a-mole with these militias; in order to win, he had to totally force the submission of the South, which would require him to conquer Virginia. On 25 April, Cornwallis marched into Virginia, hoping to link up with another British army operating in that state under the American turncoat Benedict Arnold.

Greene decided not to follow. Instead, he led his army into South Carolina to rid that state of the British troops Cornwallis had left behind. Greene would ultimately achieve this objective, after fighting two major battles at Hobkirk's Hill (25 April 1781) and Eutaw Springs (8 September 1781); Greene would famously sum up his strategy by stating, "we fight, get beat, and fight again". By the end of the year, Greene had thwarted the British attempt to pacify the South, confining their presence in South Carolina mainly to the coastline and Charleston itself. Cornwallis, meanwhile, was forced to surrender at Yorktown, Virginia, in October 1781, marking an end to the war.