Chariot racing was very big business in ancient Rome. There was a whole industry built around the factions, the four professional stables known by their team colour – Blue, Green, Red, and White –, providing all that was required for a race: horses, stable managers, blacksmiths, doctors, assistants to the charioteers, operators for the gate starting mechanisms.

In Rome, it was possible to have as many as 24 races in one day. Modern estimates suggest that 700 to 800 horses were required for a day's racing. Roman chariot drivers usually began their careers as young boys; these boys were mostly slaves bought and trained by the factions. The auriga was a less experienced charioteer and drove the two-horse chariot; with time and growing skill, he had the possibility of advancing to agitator, an accomplished and high-ranking driver who drove a four-to-ten-horse chariot. Fame and long careers could be achieved on the track; however, the track was also where many drivers lost their young lives.

Venue & Audience

The stables were situated about 2 kilometres away in the Campus Martius; horses, charioteers, and faction workers travelled from here into the Circus Maximus, the largest man-made structure in the whole of the Roman Empire. The tracks at the Circus were hazardous, with seven laps (about 5 kilometres) and 13 sharp and tight turns. The track had a divider, a 'euripus' or 'spina', this central barrier sometimes filled with water, stretched lengthwise to separate the 'up' and 'down' routes and to prevent head-on crashes. At each end of these dividers, there was a turning post. Lap markers in the shape of eggs and dolphins were turned to mark the completion of each circuit and helped make it visually possible for the audience to follow through the dust, the sun's blinding glare, and the stifling heat.

Pliny the Younger (61-112 CE) wrote of the huge popularity of the races and that he was astonished that so many thousands of men should be possessed again and again to attend the chariot races (Letters. 9.6). The popularity of the sport did not just confine itself to what one ancient writer described as the "innumerable crowd of plebians" who would hang out on streets having heated arguments over the teams (Marcellinus, Roman History. 14. 6. 26-7). It was not just the excited plebs who waited for race day, conversations could also be found at the dinner tables of the elite of Rome, where guests discussed the teams. Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) tells of Caecina a man of knightly rank from Volterra, who when at the races in Rome, would release his own swallows to despatch the news of the winning team to his friends; he painted the birds' legs the winning colour. The Circus, indeed, captivated all of Rome.

Horses & Equipment

The race circuit would have been a breathtaking and thrilling eight minutes long, with the chariots reaching possible speeds of 35 kilometres per hour and up to 72 kilometres per hour on the straight, which required great stamina and strength on the part of the charioteers and their horses. The majority of horses used were stallions. These racehorses were bred on private and imperial stud farms in North Africa, Cappadocia, Sicily, Spain, and Thessaly. Racehorses were stocky in build and comparable to a large pony of the present day. Pliny the Elder notes that "...though horses may be broken as two-years-old for other services, racing in the Circus does not claim them before five " (N.H 161-162). These horses could compete on the track up to the age of 20 years before being sent to stud.

Horses underwent thorough training for the track, some of which took place on the stud farms and then continued at equestrian training grounds such as the Trigarium in Rome's Campus Martius. In a team the most important of the horses was the introiugus, the lead horse on the left side of the chariot, it was this horse who guided the team around the turns. Pliny the Elder comments that the training of the horses must have been very intense. He recounts where a team of horses had thrown their driver at the start of the race:

... his team then took the lead and kept it by getting in the way of their rivals and jostling them aside and doing everything against them that they would have had to do with a most skilful charioteer in control ... When they had completed the course they stopped dead at the chalk line (N.H. 8.159-161).

Pliny also suggests that a horse's performance could be aided by the wearing of a large tooth of a wolf around its neck, which would stave off tiredness.

The charioteers wore protective clothing of thick leather helmets and thick tunics with horizontal leather padded bands around their chests and trunk and also around their thighs. The chariot they drove was designed with small and light wheels to help stabilise it as it took sharp turns. The body of the chariot was built small and low – a wooden framework filled in with interwoven straps for the floor, this type of floor provided a springing base. The light design of these chariots meant that they could go into skids which the inexperienced auriga had to learn to skilfully control. The drivers wrapped the chariot reins around their waists to free their whip hand. They braced their whole bodies against the reins and steered the chariot by shifting their body weight, using the left hand only to correct their course on the track. The chariot drivers with their reins tied fast about their waists now increased the risk that if they fell from their standing position they could be dragged by the chariot and thundering horses; a knife was carried by the charioteer to cut himself loose and save himself should he be taken down.

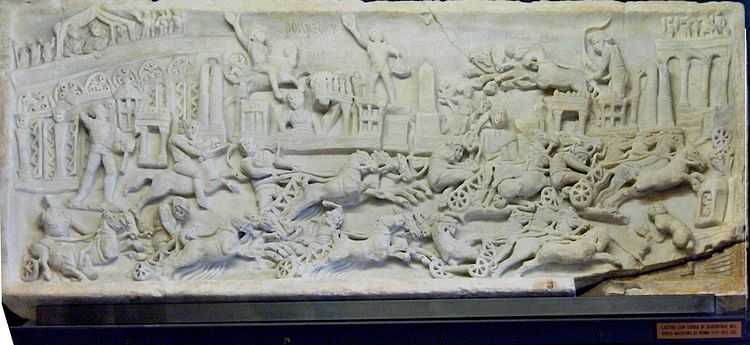

The young, unskilled driver could easily lose control "bending forward with unsteady foot...he is borne on headlong at the mercy of the horses; the axles smoke with the excessive speed..." (Sil. Pun. 283-289). Crashes occurred especially at the start of the race and on turns, as the chariot drivers jostled for position. Spectacular crashes were known as 'naufragia' (literally, "shipwrecks"); "horses were brought down, a multitude of intruding legs entering the wheels" (Sid. Apoll. Poems, 408-409). The speed of the race around the track would have meant that attendants had to work in great haste to clear the injured and the wreckage.

The Race

Before the race began, a sacred procession (pompa circensis) with images of the gods paraded through the city street ending in the Circus Maximus, where it circled the track. Following the gods, and included in the procession, were the magistrates, athletes, dancers, attendants and the charioteers, "some of whom drove four horses abreast, some two, and others rode unyoked horses" (Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom. 7.70–3). For certain races, the Circus track was sprinkled with a bright red pigment, minium, and green carbonate of copper to create the faction colours of red and green.

Placards with the names of each charioteer and horse were carried before them, increasing the anticipation as the spectators recognised the drivers. In advance of the race, and before the teams had entered the stalls, a draw was held to determine which stall each team would occupy. The lots were rolled in an urn attached to a crossbar which revolved with balls falling from the device as it was operated. The tension in the Circus would have been incredibly high with "the eyes of the spectators rolling as if with the lots" (Tert. De Spect.16). The lot, which was drawn from the urn, gave the charioteer the choice of which lane he wanted to enter for the race.

Once in their stalls, the nervous and charged horses hit madly at the gates with their hooves and their heads, "They push...they drag...they rage..." (Sid. Apoll. Poems 23. 334). Attendants aiding the charioteers tried to calm and steady the animals in the stalls as they awaited the start signal. The Circus could accommodate seven horses abreast in a stall. It was not unknown for gates to have been broken down by agitated horses and young, inexperienced charioteers swept out of control. When each charioteer was in his lane, the presiding magistrate stood to signal the beginning of the race by dropping a white handkerchief, and with that, the 12 gates of the Circus Maximus, which were placed on a shallow curve and operated by a central lever, flew open simultaneously.

The charioteers would remain in their chosen lanes until they reached the nearest end of the divider, after that the chariots went to battle for the best positions. Strategies were tactically applied, such as occupavit et vicit, to seize the lead from the beginning and win, or praemisit et vicit, where the driver intentionally allowed his opposition to get the lead at the outset and then came back to win. The drivers once free of their lanes raced anti-clockwise around the track, working in pairs, each driver stood close to the hind quarters of his horses, on the thin and flimsy chariot, which could tip easily and shatter. One of the pair of drivers worked to force and fluster opponents in order to leave a clear field for his partner. The outrider, the horator, rode behind or in front of the chariots, shouting encouragement and advice as they strategised how to avoid hairpin bends or the competitors closing in on their heels. Charioteers would veer as close as possible to the central barrier to shorten their paths. The sparsor threw water at the horses to keep them cool as they raced. To overtake on the inside as one approached the turn was a tactic greatly admired because it was extremely dangerous.

The white finishing line was situated just beyond the midpoint of the euripus. Sidonius in his poem describes a finish where the driver is reckless in his attempt to overtake and is hurled from his chariot, he lies in a twisted heap of wreckage whilst the lead charioteer, to the wild cheers of the spectators, races towards the white line (Poems 23. 323-424).

The victorious charioteer was saluted and called by the trumpeter to collect his prize; the palm of victory and the purse. On the early 3rd-century CE Severan Marble Plan, a representation of the Circus Maximus indicates a structure built into the seating area which is connected to the arena by a wide staircase which allows access to the track. The winning charioteer may have climbed up these stairs to be met and congratulated and crowned by the Roman emperor or the patron of the games. The charioteer in all his glory then made the lap of honour around the track as excited spectators threw small coins or flowers at him.

Life & Death on the Track

Charioteers' honorific and funerary inscriptions mark their successes and provide details and valuable insights into their lives. Florus was an auriga, a low-ranking and less experienced driver. His funerary inscription reads:

I, Florus, lie here, a child driver of a two horse chariot, who while I wanted to race my chariot quickly, quickly fell to the shades... (CIL. 6.10078)

Sextus Vistilius Helenus was an auriga, and his funerary inscription informs us that he had been transferred to the Blue faction where he was being coached by Datileus when he died at the tender age of 13. Crescens, another young driver, was a charioteer for the Blue faction; he was from North Africa and was probably brought to Rome as a slave. He was 13 years old when he won his first race in 115 CE. He would have been driving chariots for at least a year before that, making him 12 when he began his training. Crescens won his first race with a four-horse chariot driving the horses, Circus, Acceptor, Delicatus, and Cotynus to victory. His career lasted nine years, in which he won 1,558,346 sesterces (a soldier during this period was paid 1200 sesterces per year.) Crescens died at the age of 22.

The famous charioteer, Polynices had two sons who were also charioteers; Marcus Aurelius Polynices won 739 victory palms in his career, three purses worth 40,000 sesterces, 26 purses worth 30,000, and eleven purses of gold. Marius had driven six-, eight-, and ten-horse teams. He was 29 years old when he died. Polynices' other son, Marcus Aurelius Mollicius Tatinus, won 125 victory palms and won the 40,000 sesterces prize twice, he was just 20 years old when he died.

These young boys lived with the hazards of chariot racing and the threat of sudden and premature death, but hand in hand with the dangers was also the possibility to win fame and glory on the track. These charioteers moved between the four factions, and it is likely that they were talent-spotted by rival team managers. Charioteer Publius Aelius Gutta Calpurnianus was one of those drivers who competed for the four teams. A successful chariot driver could become famous, admired and adored and make a very comfortable living. A driver's success could ensure earning at least the amount a teacher might make in a year's tuition fees in one race. Although the substantial purses won went to the faction owners with a fraction paid to the drivers, the opportunity of being in many races over their careers meant that some charioteers could save enough to promise a good retirement.

Martial in his Epigrams refers to the famous charioteer, Scorpus, who had a huge following and was "the glory of your noisy circus, the object of your applause, your short lived favourite" (10.53, 50. 5-8). He won 2048 races and made enormous gains as a charioteer, in one race alone he won 15 bags of gold (10.74). Scorpus, reached the heights of success and knew fame and glory until he died prematurely in a crash on the track. He was just 26 years old.

The charioteer, Gaius Appuleius Diocles, born in the province of Lusitania had a spectacular 24-year-long career. He was a late starter on the track at the age of 18, winning his first at the age of 20. He spent six years with the White faction, three with the Green, and the remainder of his career with the Red. He won 1,462 races in his 24-year career. 815 of his victories came from seizing the lead at the outset of a race and holding onto it, 502 victories from winning a sprint at the end of the race, and 67 from coming from behind to overtake the leader. Successful drivers like Diocles were adored, won the hearts of the crowds, and were wined and dined by the wealthy. Diocles acquired a fortune of over 35,000,000 sesterces in his career, an income that was well in excess of any but the wealthiest of senators. He retired to live at Praeneste outside Rome and died at the age of 42.

Conclusion

Despite the hazards of the track and the real threat of death, many of these young boys showed reckless bravado with the hope of winning great fame and glory as charioteers. For those young slaves brought from the provinces, chariot racing offered the prospect of success and financial stability, and for some, widespread acclaim. Since most of these young charioteers were slaves, being successful and winning races could ultimately mean that they could also gain their freedom. Cassius Dio (c. 150-235 CE) records one such race where the crowd shouted their demand that a favourite charioteer should be given his freedom (Rom. Hist. 69.12-15).

Many charioteers would have competed as relative unknowns, and many died prematurely. However, for drivers who had outwitted death at the Circus, there could be life after the tracks. Charioteers who had finished their racing days could take up one of many positions in the factions, young men like Aurelius Heraclides, who had been a charioteer for the Blues, became a trainer for the Blues and Greens. By the late 3rd century CE, retired charioteers had greater prospects with the opportunity of becoming faction managers, a position which was once held by those of the equestrian order.