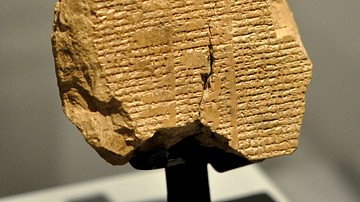

The Debate Between Sheep and Grain (c. 2000 BCE) is one of the best-known Sumerian literary debates in a genre that was popular entertainment by the late 3rd millennium BCE. In this piece, personifications of grain and sheep argue which is more important, with grain judged the winner because sheep need grain, but grain needs no sheep.

The piece is thought to have been inspired by the tension between Sumerian farmers and herdsmen who both required land. Sheepherders needed extensive land for grazing, but this was often occupied by fields of grain, and where it was not, irrigation ditches and canals presented obstacles for moving a flock. The shepherds would appeal to their goddess, Lahar, for help against the farmers while the latter appealed to their own goddess of grains, Ashnan, to protect their fields from the shepherds. The Debate Between Sheep and Grain is often interpreted as an argument between these two goddesses in the great banquet hall after they have become drunk.

The piece was popular entertainment, based on the number of copies found at the Temple Library of Nippur and elsewhere in the mid-19th through the mid-20th centuries. Debate pieces were presented in ancient Mesopotamia as dramatic performances at courts by professional actors taking the parts of the narrator and the contestants.

The Debate Between Sheep and Grain – and the other debates like it – would be comparable to a Broadway play in the modern era whose first run is exclusionary owing to the high price for tickets but, in time, moves to more modest venues accessible for lower prices. A debate piece might have begun its run in the court of a king but later be performed elsewhere for those of the lower classes, as suggested by the number of copies found in various locations.

Background

The origin of the debate genre is unclear, but once established, it became a standard part of the curriculum of the edubba ("House of Tablets"), the Sumerian scribal schools. The Debate Between Sheep and Grain was included as one of the more difficult pieces a student needed to master after passing through the Tetrad and Decad phases of instruction. How they might have been used in schools is unclear – they may have been performed by more than one student or recited only by the one who had copied it – but by the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE) they were performed regularly at court. Scholar Jeremy Black comments:

Formal debates were a popular entertainment at the court of the kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur. Records survive indicating that payments were made to the performers who took part. Typically, the contest is between two natural phenomena, animals, or materials that are significant to human life: Winter and Summer, Bird and Fish, Sheep and Grain, Tree and Reed, Date Palm and Tamarisk, Hoe and Plough, Silver and Copper. The debate progresses as each contestant, personified, speaks alternately, often with considerable acrimony. Each tries to persuade the audience that it is more beneficial to mankind than the other. (225)

The debate is usually concluded by a king or god declaring the winner. In the case of The Debate Between Sheep and Grain, Enki, the god of wisdom, decides in favor of Grain, and Enlil, the Father God, decrees it so.

Summary

The poem begins as a creation myth in the time of the ancient Anunna gods, before grain or sheep existed and so prior to the time of the younger gods such as Uttu (goddess of weaving, not to be confused with Utu-Shamash, the sun god) or Ningiszida (an underworld, vegetative god associated with agriculture, here possibly given as Nigir-sig in line 16) or Sakkan (the lord of herds and wild animals, sometimes given as Cakkan). The reference to Ezina-Kusu in line 11 is to the other names for (or aspects of) the goddess Ashnan who became more prominent after the earlier agricultural goddess, Nisaba, became the deity of writing.

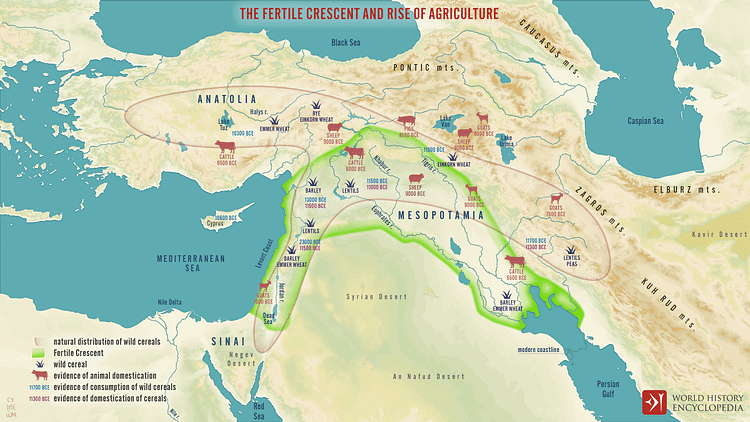

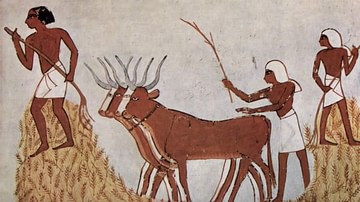

In lines 26-36, the gods create Grain and Sheep but find they do not make satisfying meals and so decide to send them down from their Holy Mountain to the humans. Lines 43-53 depict humanity's interaction with Sheep and Grain, fencing in the one and cultivating the other, a reference to what is now known as animal husbandry and the Agricultural Revolution. Whether domestication of animals or plants was more important to the development of civilization is a debate ongoing in the present day and this piece is understood as the earliest expression of that argument.

Sheep and Grain – Lahar and Ashnan – make the world beautiful and the gods An (Anu) and Enlil are satisfied with their decision. Trouble begins when Sheep and Grain become drunk in the dining hall, and Grain claims it is superior to Sheep (lines 65-91). The rest of the poem gives the back-and-forth of the two contestants until lines 180-191 when Enki convinces Enlil to proclaim Grain the winner because it does not need Sheep, but Sheep cannot live without Grain. The last lines end with praise to Enki for his wisdom in recognizing that agriculture is more important than animal husbandry.

The Text

The following passage is taken from The Literature of Ancient Sumer, translated by Jeremy Black et al. Ellipses indicate missing words or lines, and question marks suggest an alternate translation for a word or phrase.

1-11: When, upon the hill of heaven and earth, An spawned the Anuna gods, since he neither spawned nor created Grain with them, and since in the Land he neither fashioned the yarn of Uttu (the goddess of weaving) nor pegged out the loom for Uttu – with no Sheep appearing, there were no numerous lambs, and with no goats, there were no numerous kids, the sheep did not give birth to her twin lambs, and the goat did not give birth to her triplet kids; the Anuna, the great gods, did not even know the names Ezina-Kusu (Grain) or Sheep.

12-25: There was no muc grain of thirty days; there was no muc grain of forty days; there was no muc grain of fifty days; there was no small grain, grain from the mountains or grain from the holy habitations. There was no cloth to wear; Uttu had not been born – no royal turban was worn; lord Nigir-sig, the precious lord, had not been born; Sakkan (the god of wild animals) had not gone out into the barren lands. The people of those days did not know about eating bread. They did not know about wearing clothes; they went about with naked limbs in the Land. Like sheep they ate grass with their mouths and drank water from the ditches.

26-36: At that time, at the place of the gods' formation, in their own home, on the Holy Mound, they created Sheep and Grain. Having gathered them in the divine banqueting chamber, the Anuna gods of the Holy Mound partook of the bounty of Sheep and Grain but were not sated; the Anuna gods of the Holy Mound partook of the sweet milk of their holy sheepfold but were not sated. For their own well-being in the holy sheepfold, they gave them to mankind as sustenance.

37-42: At that time Enki spoke to Enlil: "Father Enlil, now Sheep and Grain have been created on the Holy Mound, let us send them down from the Holy Mound." Enki and Enlil, having spoken their holy word, sent Sheep and Grain down from the Holy Mound.

43-53: Sheep being fenced in by her sheepfold, they gave her grass and herbs generously. For Grain they made her field and gave her the plough, yoke and team. Sheep standing in her sheepfold was a shepherd of the sheepfolds brimming with charm. Grain standing in her furrow was a beautiful girl radiating charm; lifting her raised head up from the field she was suffused with the bounty of heaven. Sheep and Grain had a radiant appearance.

54-64: They brought wealth to the assembly. They brought sustenance to the Land. They fulfilled the ordinances of the gods. They filled the storerooms of the Land with stock. The barns of the Land were heavy with them. When they entered the homes of the poor who crouch in the dust, they brought wealth. Both of them, wherever they directed their steps, added to the riches of the household with their weight. Where they stood, they were satisfying; where they settled, they were seemly. They gladdened the heart of An and the heart of Enlil.

65-70: They drank sweet wine, they enjoyed sweet beer. When they had drunk sweet wine and enjoyed sweet beer, they started a quarrel concerning the arable fields, they began a debate in the dining hall.

71-82: Grain called out to Sheep: "Sister, I am your better; I take precedence over you. I am the glory of the lights of the Land. I grant my power to the sajursaj (a member of the cultic personnel of Inanna) – he fills the palace with awe and people spread his fame to the borders of the Land. I am the gift of the Anuna gods. I am central to all princes. After I have conferred my power on the warrior, when he goes to war he knows no fear, he knows no faltering (?) – I make him leave ... as if to the playing field."

83-91: "I foster neighbourliness and friendliness. I sort out quarrels started between neighbours. When I come upon a captive youth and give him his destiny, he forgets his despondent heart and I release his fetters and shackles. I am Ezina-Kusu (Grain); I am Enlil's daughter. In sheep shacks and milking pens scattered on the high plain, what can you put against me? Answer me what you can reply!"

92-101: Thereupon Sheep answered Grain: "My sister, whatever are you saying? An, king of the gods, made me descend from the holy place, my most precious place. All the yarns of Uttu, the splendour of kingship, belong to me. Sakkan, king of the mountain, embosses the king's emblems and puts his implements in order. He twists a giant rope against the great peaks of the rebel land. He ... the sling, the quiver and the longbows."

102-106: "The watch over the elite troops is mine. Sustenance of the workers in the field is mine: the waterskin of cool water and the sandals are mine. Sweet oil, the fragrance of the gods, mixed (?) oil, pressed oil, aromatic oil, cedar oil for offerings are mine."

107-115: "In the gown, my cloth of white wool, the king rejoices on his throne. My body glistens on the flesh of the great gods. After the purification priests, the incantation priests and the bathed priests have dressed themselves in me for my holy lustration, I walk with them to my holy meal. But your harrow, ploughshare, binding and strap are tools that can be utterly destroyed. What can you put against me? Answer me what you can reply!"

116-122: Again, Grain addressed Sheep: "When the beer dough has been carefully prepared in the oven, and the mash tended in the oven, Ninkasi (the goddess of beer) mixes them for me while your big billy-goats and rams are dispatched for my banquets. On their thick legs they are made to stand separate from my produce."

123-129: "Your shepherd on the high plain eyes my produce enviously; when I am standing in the furrow in the field, my farmer chases away your herdsman with his cudgel. Even when they look out for you, from the open country to the hidden places, your fears are not removed from you: fanged (?) snakes and bandits, the creatures of the desert, want your life on the high plain."

130-142: "Every night your count is made, and your tally-stick put into the ground, so your herdsman can tell people how many ewes there are and how many young lambs, and how many goats and how many young kids. When gentle winds blow through the city and strong winds scatter, they build a milking pen for you; but when gentle winds blow through the city and strong winds scatter, I stand up as an equal to Iskur (the god of storms). I am Grain, I am born for the warrior – I do not give up. The churn, the vat on legs (?), the adornments of shepherding, make up your properties. What can you put against me? Answer me what you can reply!"

143-155: Again, Sheep answered Grain: "You, like holy Inanna of heaven, love horses. When a banished enemy, a slave from the mountains or a labourer with a poor wife and small children comes, bound with his rope of one cubit, to the threshing-floor or is taken away from (?) the threshing-floor, when his cudgel pounds your face, pounds your mouth, as a pestle (?) ... your ears (?) ... and you are ... around by the south wind and the north wind. The mortar ... As if it were pumice (?) it makes your body into flour."

156-168: "When you fill the trough the baker's assistant mixes you and throws you on the floor, and the baker's girl flattens you out broadly. You are put into the oven and you are taken out of the oven. When you are put on the table I am before you – you are behind me. Grain, heed yourself! You too, just like me, are meant to be eaten. At the inspection of your essence, why should it be I who come second? Is the miller not evil? What can you put against me? Answer me what you can reply!"

169-179: Then Grain was hurt in her pride and hastened for the verdict. Grain answered Sheep: "As for you, Iskur is your master, Sakkan your herdsman, and the dry land your bed. Like fire beaten down (?) in houses and in fields, like small flying birds chased from the door of a house, you are turned into the lame and the weak of the Land. Should I really bow my neck before you? You are distributed into various measuring-containers. When your innards are taken away by the people in the marketplace, and when your neck is wrapped with your very own loincloth, one man says to another: 'Fill the measuring-container with grain for my ewe!'"

180-191: Then Enki spoke to Enlil: "Father Enlil, Sheep and Grain should be sisters! They should stand together! Of their threefold metal ... shall not cease. But of the two, Grain shall be the greater. Let Sheep fall on her knees before Grain. Let her kiss the feet of ... From sunrise till sunset, may the name of Grain be praised. People should submit to the yoke of Grain. Whoever has silver, whoever has jewels, whoever has cattle, whoever has sheep shall take a seat at the gate of whoever has grain, and pass his time there."

192-193: Dispute spoken between Sheep and Grain: Sheep is left behind and Grain comes forward – praise be to Father Enki!

Conclusion

The Debate Between Sheep and Grain would have been performed in rotation with other debate pieces including The Debate Between Plough and Hoe, The Debate Between Bird and Fish, The Debate Between Winter and Summer, and other similar titles, all of which seem to have been popular entertainment for all the Mesopotamian social classes. As noted, The Debate Between Sheep and Grain appears to have been especially popular but multiple copies of others have also come to light.

It is unclear how long the debate genre pieces were performed, but they were still in use by scribal schools during the Neo-Assyrian Period (c. 912-612 BCE) and included in the collection of the Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh. When the Assyrian Empire fell in 612 BCE, and Nineveh was sacked and burned, the fires baked the clay tablets of the library and the fallen walls covered them, preserving them for over 2,000 years until they were discovered in 1849 by Sir Austen Henry Layard. First translated in 1918, The Debate Between Sheep and Grain has since delighted readers as much as it once did its ancient audiences.