On Faith and Works (1532) by Cardinal Thomas Cajetan (l. c. 1468-1534) is a refutation of the central arguments of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) concerning justification before God as faith-based, having nothing to do with one’s works. Cajetan shows why Luther is wrong in this while reaffirming the Catholic stand on the importance of faith and works.

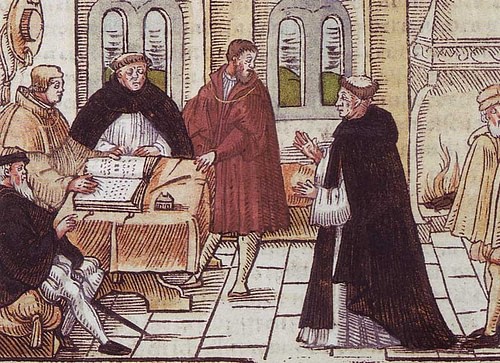

Martin Luther met Cardinal Cajetan at Augsburg in 1518 for disputation following the publication of Luther’s 95 Theses in 1517. Cajetan had hoped to bring Luther back to the Church through gentle admonishment, but Luther rejected this approach and Cajetan’s arguments. Following this, Cajetan returned to Rome and helped draft the papal bull Exsurge Domine threatening Luther with excommunication. Once Luther was excommunicated in 1521, Cajetan continued to defend the Catholic Church against the “new teachings” of Luther, culminating in his masterpiece, On Faith and Works in 1532.

The piece is divided into twelve sections: eleven arguments and a summation:

1.The Lutheran Doctrine of Faith

2. A First Error: Equivocal Use of the Term “Faith”

3. The Second Error: Teaching That This Conviction Attains Forgiveness of Sins

4. The Third Error: Forgiveness of Sins Preceding Charity

5. The Lutheran Teaching on Works

6. The Meaning of Merit in This Context

7. Human Works Merit Something from God

8. Eternal Life Merited by Living Members of Christ

9. How Our Works Merit Eternal Life

10. Works Performed in Mortal Sin

11. Works Satisfying for Sin

12. Response to Objections

On Faith and Works made no impression on Luther or Lutheran doctrine but did inform the discussions and conclusions of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) and the Catholic Counter-Reformation (1545-c.1700) which reestablished the authority of the Church while also amending earlier errors and abuses. The work remains a classic of Catholic theology and is among the most significant of the early era of the Protestant Reformation.

Background and the Argument

Martin Luther’s problems with the Church began after he connected spiritually with the line from Romans 1:17 - “the just shall live by faith” – which led him to conclude that one only needed faith in God and the Bible for a personal relationship with the Divine. One’s faith opened up the lines of communication with God who then spoke to the believer through scripture. This being so, he reasoned, the Church was nothing more than an artifice constructed by human beings and its policies and teachings should be rejected as impediments to faith.

In October 1517, Luther posted his 95 Theses criticizing the Church’s policy of selling indulgences – writs granting leniency to shorten one’s time (or that of a loved one) in purgatory – and when the Church reacted by trying to silence him, Luther published more works against the Church which, thanks to the invention of the printing press, were widely circulated, winning him greater support. Cajetan had tried to coax Luther back to orthodoxy at Augsburg in 1518 and, when that attempt failed, joined with others, including the theologian Johann Eck (l. 1486-1543), in drafting the papal bull Exsurge Domine (“Arise, O Lord” in Latin), threatening Luther with excommunication in 1520. After Luther burned the bull in December of that year, he was excommunicated in January 1521.

Cajetan continued to denounce what he saw as Luther’s errors and heresies for the next ten years before writing On Faith and Works which systematically explained why Luther was wrong in rejecting the Church and its teachings as well as why, and how, the Church’s doctrine was sound and in accordance with scripture. At the heart of Luther’s argument, Cajetan argued, was a misunderstanding of the concepts of “faith” and of “works”. To Luther, Cajetan claims, “faith” is one’s personal conviction in one’s own rightness in understanding God but, he points out, the Bible makes clear that “faith” is far less concrete and is, in the words of Hebrews 11:1, “the evidence of things unseen”, the belief in an ineffable Higher Power, having far less to do with one’s own convictions than with God’s presence and an objective conviction of one’s sins and need for redemption.

Cajetan continues with “works”, noting that Luther rejects the Catholic doctrine that works accrue merit to the believer since he maintains that all one needs is faith and, to Luther, one’s works are simply the fruit of one’s faith, the physical manifestation of one’s inner conviction. Cajetan argues that this incorrect because the believer does not accrue merit by their own actions but through their participation in the body of Christ that is the Church.

As Cajetan points out, one does not seek merit for what one already has but for what one does not – one does not ask for a raise if one is satisfied with one’s present salary – and so the believer is aware of what is lacking as a servant of Christ and accrues merit, satisfying that lack, through good works empowered, not by the believer, but by Christ. This empowerment is only available, he argues, through the Church as the Bride of Christ or as the Body of Christ of which he is the head.

Progression of the Argument

Cajetan begins his argument by defining the Lutheran Doctrine of Faith with its emphasis on faith-alone as the means by which one is justified before God and how “faith” is defined as personal conviction – “but if in receiving the sacrament one firmly believes he is justified, then he is truly justified” (Janz, 387). He then argues that this definition of “faith” as “personal conviction” is not supported by the Bible (First Error, Section 2) before addressing the claim that one’s personal conviction regarding faith attains forgiveness of sins (Section 3).

Having established what Luther claims, and what the Bible says on the subject, Cajetan moves to Section 4 in which he dismisses Luther’s argument that one can be forgiven of one’s sins without receiving the love (charity) of God which brings him to Section 5 and Luther’s Teaching on Works claiming they are the fruits of faith but have no intrinsic worth of their own to salvation. Cajetan argues against this claim in Sections 6 and 7 and then explains his points further in 8 and 9 before addressing the question of Works Performed in Mortal Sin (Section 10) where he writes:

We agree that the works performed by persons in mortal sin are neither meritorious for eternal life nor of the forgiveness of sins. Nonetheless, they are of considerable importance for a man caught in mortal sin, since Holy Scripture says they lead to attaining forgiveness of sins. (Janz, 396)

In the same section, in answer to the Lutheran claim that only one’s faith is required for salvation, Cajetan cites Isaiah 1: 16-18 in support of the claim that one must perform some kind of act to show oneself worthy of God’s forgiveness. One cannot simply claim forgiveness on the grounds of one’s faith but must show contrition and repentance as is seen in the Isaiah passage:

Wash yourselves, make yourselves clean, remove the evil of your thoughts from my sight, cease to act wickedly; learn to do good and seek what is right, aiding the oppressed, defending the orphan, and taking the part of the widow, and we can reason together, says the Lord. If your sins are like scarlet, yet they will become white as snow, if red like crimson, they will become like white wool.

From this point, he moves to his argument on Works Satisfying for Sin (Section 11) where, informed by the Isaiah passage, he argues against the Lutheran position that once one’s sins are forgiven through one’s acceptance of Christ, there is no need for penance or works of atonement. Referencing the Bible, Cajetan makes clear that scripture calls for a person to accept responsibility for their actions and perform some act of penance in the hope of forgiveness. He then concludes his argument with a summation of points in Section 12 which follows below.

The Text

In the following excerpt – Response to Objections – Cajetan sums up the arguments of the first eleven parts while also anticipating and answering objections to his claims. The excerpt is taken from A Reformation Reader: Primary Texts with Introductions, edited by Denis R. Franz, pp. 398-400.

It remains for us to answer the objections. The first arose from the sufficiency of the merit and satisfaction of Christ. We answer that the merit of Christ was completely and utterly sufficient, and that this satisfaction was more than adequate for our sins and for the sins of the whole world, including original sin, mortal sins, and venial sins, as I John 2:2 teaches. Therefore, it is not because of an inadequacy in the merit and satisfaction of Christ that we attribute merit and satisfaction to the works of Christ’s living members, but rather because of the excessive riches of Christ’s merit which he shares with his living members so that their works as well may be meritorious and satisfactory. A greater grace is conferred on us by Christ when he, our head, merits and satisfies in and through us his members than if we were only to share in the merit Christ gained in his own person.

To the objection that what is proper to Christ must not be attributed to us, we answer that it should not be attributed to us in the manner in which it is proper to Christ. It can be attributed to us in another manner, namely, by participation. Something proper to God can be attributed to no one in that manner proper to God, but it can be shared by others by participation. For instance, the vision of the divine essence is proper to God, and no creature can see God as he is, since he alone by his own nature sees himself. But God can, by grace, grant a share in the vision of God, and this he does to all the blessed. In the present case, merit of eternal life is proper to Christ, when this is understood as merit by one’s own power. But this can be granted to his living members, not that they merit by their own power, but that they merit by the power of Christ the head. The same thing can be understood concerning satisfaction.

There is no need to respond concerning the forgiveness of sins, since we already said that this is not granted to Christ’s living members, because their good works presuppose that their sins have been forgiven. No one merits that which he already has. Merit is gained concerning something not had. For this reason, Christ apportions to his members the merit of an increase in grace and of heavenly beatitude. He does not apportion to them merit of forgiveness of sins. Eternal beatitude is something lacking to Christ’s members in this life, while they do have forgiveness of sins by the very fact of becoming members of Christ. No one merits what he has but what he hopes to attain. This makes it clear that our merits and satisfactions in no way detract from the merit and satisfaction of Christ, but rather that the grace of merit and satisfaction Christ gained in his own person is extended to himself as Head working in and through his members.

All the texts cited as showing that we do not by our works merit the forgiveness of sins require no answer, since we agree with this conclusion. But we must respond to the texts cited to prove that we do not merit eternal life by our works. To the text of the apostle from Romans, “The gift of God is eternal life” (6:23), we answer that we indeed say and teach this, since it is by God’s gift of sanctifying grace that we are members of Christ and by the power in us of Christ the Head that we merit eternal life. We do not say that we merit eternal life through our works specifically as ours, but in so far as they are in us and through us from Christ.

We propose the same distinction in answer to the objection raised from Christ’s words, “Say, `we are unworthy servants’” (Luke 17:10). However much we might fulfill all the commandments of Christ, to the extent we fulfill them by our own free choice, we are unworthy servants regarding our Father’s heavenly household. We are unworthy of our homeland in heaven and whatever concerns it, such as the forgiveness of sins, the grace of the Holy spirit, charity, and other things proper to God’s children. The reason is obvious, since when we act on our own, we are too weak to reach the higher order in which are conferred the proper goods of God’s children. This goes together with the other truth, namely, that insofar as our deeds proceed from the influence in us of Christ the Head in his living members, we can contribute much through our works to gaining the heavenly homeland and our Father’s household. As his members, we are raised to the order of God’s children, not to be unworthy servants, but worthy members of our Father’s household and the heavenly homeland.

An argument can be made from these words of Christ against the capability of good works done in a state of mortal sin to impetrate the forgiveness of sins…If the argument is made that our good works have no usefulness in impetrating the forgiveness of sins, we answer that insofar as prayer, fasting, alms, and other good works arise from them as sinners, they are not capable of impetrating [entreating] forgiveness of sins. But insofar as the divine goodness orders them to impetrating forgiveness of sins, they are highly effective for impetrating this. Consequently, in Ezekiel, these works are called “the ways of God” and not “our ways” (18:29). The divine goodness has arranged that we impetrate many things we never merit. As Christ, Isaiah, Ezekiel, and the apostle (in Hebrews) bear witness, the divine goodness has conferred on the good works of persons returning to God the power of impetrating the forgiveness of sins from the divine mercy through the merit of Christ. Because of this, the fasting, prayers, alms, and other righteous works of sinners are beneficial, not for meriting, nor for satisfying, but for impetrating forgiveness of their sins.

This, I believe, will suffice to explain these questions about faith and works. May it bring glory to almighty God and consolation to the devout. Rome, 13 May 1532.

Conclusion

By the time Cajetan published On Faith and Works, Luther’s movement was well-established, Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) had already founded his Reformed Church in Switzerland and died in the Kappel Wars in 1531, and John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) had converted to the Protestant vision of Christianity. None of these Protestant leaders, nor their followers, were interested in Cajetan’s argument on faith or works as they had already strongly identified with the faith-alone doctrine first advanced by Luther and based on biblical texts such as Ephesians 2:8-9: “For by grace you have been saved, through faith, and this not of yourselves, it is the gift of God, not of works, lest any man should boast.”

Cajetan’s argument on the merit of good works ran counter to Luther’s stand which, as Cajetan and Eck and others pointed out, ignored biblical passages which supported the merits of good works and their importance to faith such as James 2:18 – “Yea, a man may say, Thou hast faith and I have works; show me thy faith without thy works, and I will show thee my faith by my works” – or I Corinthians 15:58 – “Abound in every good work, knowing that your labor is not in vain in the Lord.”

When Cajetan died in 1534, the Lutherans and other Protestant sects were still ignoring his work, but it would help inform the Catholic response to the Reformation that would condemn Protestantism as a heresy. Among the decrees of the Council of Trent were a number that resonated with Cajetan’s arguments, among them the decree on The Fruits of Justification/Merits of Good Works, stating one is saved, not by faith alone, but by works which glorify God. Cajetan’s claims regarding faith and works are still rejected by Protestant churches in the present day while remaining central to Catholic doctrine, as they have been since the Council of Trent.