Elements of Norse mythology abound in The Lord of the Rings, and none is so compelling as the ring itself. The One Ring is reminiscent of magic rings in Norse lore, especially Odin's Draupnir or Andvaranaut from the legend of the Volsungs, although Tolkien's ring has a will of its own and cannot be used for the good.

Andvari's Ring

In the Völsunga saga – a story also presented in a fragmentary and less cohesive form in the Poetic Edda (the 1200s collection of Norse poems of different times and authors) after the poems involving the gods and also present in the continental Germanic tradition as Das Nibelungenlied – the cursed ring of Andvari brings the doom of the hero Sigurd (Siegfried) from the Volsung clan. J. R. R. Tolkien, who had also studied Old Norse, attempted his own reworking of this legendary material in The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún, even adding a mythological introduction following the example of the Völuspá, the prophecy that initiates the Poetic Edda.

This same impulse towards tying up loose ends is a reoccurring feature of Tolkien's relationship to his Norse sources, but these gaps would eventually come to accommodate a world the author had created for himself. (Birkett, 249)

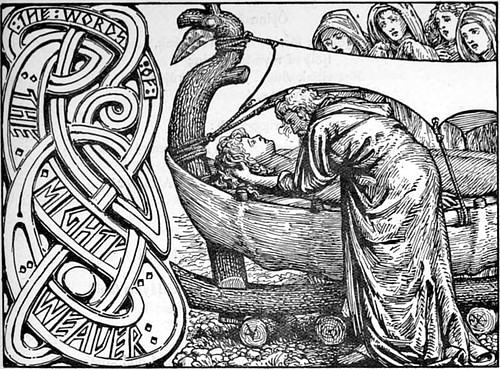

In the Old Norse source, the ring forms part of the compensation that the gods Odin, Hoenir, and Loki have to pay to a certain king Hreidmar, after killing Ótr, his otter shapeshifting son while out fishing. Loki needs to find the ransom, and he uses the gold of the dwarf Andvari (the Weary), captured while swimming in the form of a pike. The dwarf wants to keep one ring, but Loki takes it off. In exchange, Andvari curses all the gold to cause the death of whoever owns it. The gods then take the gold and fill up the otter skin, covering it inside and outside, but when king Hreidmar notices one whisker, he demands it be covered, too. Odin takes the cursed ring, Andvaranaut, and covers the whisker, fulfilling the compensation.

Egged on by his instructor Regin, another son of Hreidmar, Sigurd of the Volsung family slays the dragon Fafnir, the third son, turned into a monster by his greed (a stark reminder of The Hobbit's Smaug). He becomes the new master of the treasure, and he sets off to ride through a ring of fire to free the valkyrie Brynhild, who receives the ring as a love token. Later in the story, when a magic potion makes him forget about the valkyrie and marry Gudrun, he comes to her in the shape of her husband Gunnar, Gudrun's brother and king of the Burgundians, and replaces the ring. Overall, Andvari's ring more likely functions as a reminder of the hero's inevitable fate following the enchantment of a hoard obtained by force, and it does not share the malevolence and might of Tolkien's ring.

Like the ring in Wagner's Ring der Nibelungen – a misappropriation of legendary material serving fascist propaganda – Tolkien's ring possesses extreme power. "Both rings are round, and there the resemblance ceases", Tolkien said in one of his letters (The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. A Selection 229), but there is one important point of resemblance: both works turned the ring into a major character. On the other hand, it might have been a conscious attempt to counter the racial supremacist approach, as in other letters (55-56) he objected to the National-Socialists turning the Norse culture that he adored into something despicable.

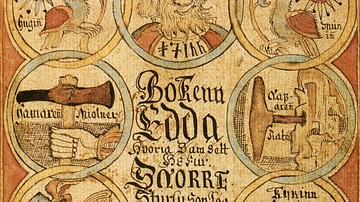

In Tolkien's work, the quest to destroy the ring is as central as the object itself, and the unexpected hero, a member of the not so steely and warmongering race of hobbits, counteracts the martial 'Germanic' prototype. His hero attempts to be a praiseworthy figure of peace, which can be inferred from his name. In the Ynglinga Saga (a mythical prehistory of Scandinavia), there are a few characters named Frøði ("Wise"), one in particular linked to an extended reign of prosperity, attributed to the god Freyr who gave good harvests (Heimskringla, chapter 10). In Snorri Sturluson's 13th-century Prose Edda, the peace of Frodi (Fróða friðr) comes as a parallel to Roman emperor Augustus' (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) Pax Romana, but because this Frodi, a king of the Danes descended from Odin (the legendary Skjöldungar), seems to be the most powerful king of the North, Snorri explains that the Northmen call this world event the peace of Frodi. During this time no one harmed anyone else, and there were neither robbers nor thieves so that a gold ring could lay long on Ialangr heath (Jelling in Denmark). The period's prosperity is due to two millstones that could grind whatever the grinder wished for, in this case, gold. So we have this small detail of a golden ring and resisting temptation, during the reign of Frodi, that could also have sparked the author's imagination.

Odin's Ring

The idea of a master ring could be further connected to Odin's Draupnir (the Dripper, from the verb drjúpa), the golden arm ring that he places on his son Baldr's funeral pyre and which has the power to replicate itself by 'dripping' eight rings of equal weight every ninth night. We get a lot of details on this account from Snorri and hints from the more archaic poems of the Poetic Edda. In chapter 35 of the Skáldskaparmál, the section devoted to teaching the art of poetry, we catch a glimpse into the broader context of this ring in the story about why gold is called the hair of Sif (Thor's wife).

The cunning god Loki cuts off Sif's hair, and Thor threatens to break every bone of his body unless he fixes it. Therefore he first pays a visit to the dark elves called the sons of Ivaldi (svartálfar in Old Norse, probably dwarves, as the difference between these groups is unclear). These great craftsmen forge not only Sif's hair, but also the magic ship Skidbladnir that could fit into a pocket, and Odin’s spear Gungnir, which never misses. Then Loki wagers his head with the dwarves Brokk and Sindri (or Eitri depending on the manuscript) that they cannot forge better objects. Despite the attempts of a fly (most likely Loki in disguise) to sabotage their work by nibbling on Brokk's neck and eyelids, the smiths produce a boar with bristles of gold, the golden ring Draupnir, and Thor's hammer Mjölnir. These precious gifts are presented to the gods. Odin gets the spear and the ring.

The ability of Draupnir to self-replicate parallels that of the One Ring to dominate all others and "perceive all the things that were done by means of the lesser rings, and he could see and govern the very thoughts of those that wore them" (The Silmarillion, 361). After Celebrimbor, a great elven craftsman of Eregion, uses the knowledge provided by Sauron disguised as an emissary of the Valar (primeval angelic powers) to shape the three elven rings, Sauron presents nine rings to mortal men doomed to become the Nazgûl, the Ringwraiths, and the seven to the dwarf-lords, who use them to establish their fabled treasure hoards that would end up attracting dragons (resembling the tale of Fafnir). The theme of smithing and great smiths, with both elves and dwarves involved in the process, such as Tolkien's Feanor who forges the three great Jewels and the Norse/Germanic Völund (Wayland), the elf imprisoned by a king who takes revenge by killing his sons and crafting a winged cloak, is reminiscent of Norse myth.

In the Norse context, the ring may refer to the potential followers of Odin, in that arm rings were a common gift from a lord. For Odin, the ring clearly has a lesser significance. Sauron puts all his will to destruction into the ring, and Tolkien's decision about its potency has moral implications: the mythical separation of your soul into an external object that becomes your main source of power exposes disastrous consequences. The narrative differs quite a bit, since the dwarves forge Draupnir at the instigation of the great troublemaker Loki, while Sauron tends to the task himself and crafts it in Orodruin, Mount Doom, with a clear purpose to ensnare the users of all rings of power.

In the section Gylfaginning (The Deceiving of King Gylfi) of the Prose Edda, we find out that Odin actually places the arm-ring on the pyre of Baldr, after the tragic death at the hands of his blind brother Hodr instigated by Loki. Another brother of Baldr, Hermod, rides to hell in the attempt to convince Hel, daughter of Loki and keeper of the underworld, to let him return because of the great mourning among the Æsir. Baldr sends Draupnir back to Odin as a keepsake, among other gifts. The gods send envoys all over the world to convince all living things to weep Baldr out of hell, an impossible task due to Loki's refusal (disguised as a giantess).

Draupnir also comes up in kennings (complex metaphors) for gold, for example, Snorri quotes the Lay of Bjarki where gold can also be replaced with "Draupnir's precious sweat" (Old Norse: Draupnis dýrsveita, chapter 45 of Skáldskaparmál). 'Precious', of course, became a leitmotif in Tolkien's work. Unfortunately, in the older source, Draupnir is a rather scarce presence, and the poem featuring it does not endow it with other special powers, although it remains significant. After its retrieval from Hel, Freyr's servant Skirnir offers it to the giantess Freyr wants to wed. The reference is found in the poem Fǫr Skirnir (Skirnir’s Journey), stanza 21. Although the ring is not named, we can surely identify it as Draupnir:

The arm-ring I bring you

that was burnt

long ago with Odin's son,

eight of equal weight

drip from it

on every ninth night.

(author's translation)

We have no information on why and how Draupnir ends up with Freyr. The poem uses the term baugr (arm-ring) as these were more common in the Norse world, but a regular ring seems more fitting for Tolkien's narrative since it has to remain out of sight and its might has to contrast with its size.

The indestructible nature of these rings is another common theme – the One Ring can only be molten where it was crafted. Moreover, the power of the One Ring is increased by the taboo surrounding its name. It is either nameless or too terrifying to name, while other rings in Tolkien's legendarium do receive names: Galadriel's ring of healing Nenya, Elrond's mighty ring Vilya, and Narya the Great, the one Gandalf openly wears in the ninth chapter of The Return of the King, a point in the story where all these rings are passing out of the Middle Earth. Gandalf, Tolkien's Odinic wanderer, shares common traits with the Allfather, such as their abilities in sorcery, the quest for knowledge obtained through sacrifice, exploration of the earth in the shape of old men, and also the animals and gear they carry – the ring included.

In a letter, Tolkien explained the hiding of the elven rings once the dark intentions of Sauron became obvious, as well as the famous ancient rhyme that appears as a leitmotif in The Lord of the Rings:

The Elves of Eregion made Three supremely beautiful and powerful rings, almost solely of their own imagination, and directed to the preservation of beauty: they did not confer invisibility. But secretly in the subterranean Fire, in his own Black Land, Sauron made One Ring, the Ruling Ring that contained the powers of all the others, and controlled them, so that its wearer could see the thoughts of all those that used the lesser rings, could govern all that they did, and in the end could utterly enslave them. He reckoned, however, without the wisdom and subtle perceptions of the Elves. The moment he assumed the One, they were aware of it, and of his secret purpose, and were afraid. They hid the Three Rings, so that not even Sauron ever discovered where they were and they remained unsullied. The others they tried to destroy. In the resulting war between Sauron and the Elves Middle-earth, especially in the west, was further ruined. Eregion was captured and destroyed, and Sauron seized many Rings of Power. These he gave, for their ultimate corruption and enslavement, to those who would accept them out of ambition or greed (The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. A Selection, 131).

Ambition and greed remind us of destiny's fatalities in the Sigurd cycle.

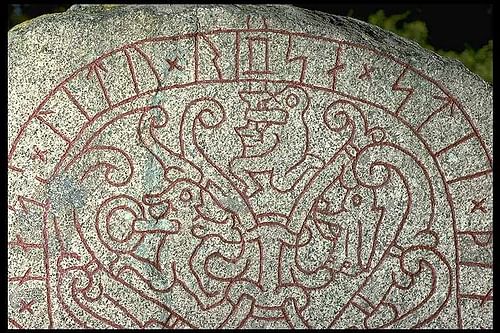

Rings of Oath & Power

One more aspect that further associates Norse tradition with Tolkien's legendarium is the idea of swearing oaths on rings usually kept in a temple. In the Eyrbyggja saga (Saga of the Ere-Dwellers), the author describes a pedestal in the middle of a room – the place for sacrificial animal blood – with a 500-gram (20-ounce) arm-ring on top, where men swore their oaths. Worn by the temple priest, the ring appears to function as a binding magical contract between men and gods. In the poem Atlakviða (The Lay of Atli), one of the oldest Eddic poems, Atli swears by the ring (a finger ring this time) of the god Ull. The Russian Primary Chronicle describes how Vikings swear by their weapons and arm-rings to endorse a treaty with the Byzantines. In the mid 800s, Guthrum's Vikings entered a treaty with King Alfred the Great (r. 871-899) by offering an oath on a holy bracelet. The vast amount of arm-rings, finger rings, and neck-rings (torques) documented archaeologically in Scandinavia confirms their extended use, with Vikings often linking them to oaths and rewarding loyalty with these valuable objects.

In The Lord of The Rings, as Frodo tries to convince Sam of Gollum's obedience, Gollum seeks to swear on the Precious himself, but his oath not to harm Frodo is eventually made by and not on the ring. This meagre difference suggests the importance of keeping the treacherous ring out of Gollum's reach. Similarly, the ring functions as an indirect keeper of oaths when Faramir requests an oath to release Gollum into Frodo's custody, and the creature swears never to lead others to the location of the Precious.

In Norse society, rings often had positive connotations, as they were a common gift after successful battles, and chieftains were described as givers of rings. In Old English poems, kings are called both ring-givers (béaga brytta) and gold-givers (goldgyfa), and they are condemned if they hoard everything for themselves. In Norse and Anglo-Saxon society, chieftains were expected to honour their followers, and Tolkien explores these ideas in several ways. There is, of course, Sauron's gift-giving, but also Isildur, who takes the ring as compensation for his father and brother. On the other hand, the Ring-bearer faces an outlandish burden that will weigh heavier and heavier until the climax, with no other unravelling than destruction. Apart from the three good elven rings, in Tolkien's universe, many rings serve as a warning about externalising power into an item which then becomes your identity. The One exposes the frailty of his bearer.

Conclusion

As with other aspects of his work, ranging from supernatural creatures, the naming of characters – famously Gandalf is a name from the Norse dwarf catalogue, meaning an elf with a staff – to heroic landscapes and riddle contests, Old Norse myth has been serving its purpose as a pillar of Tolkien's Middle-Earth, alongside Old English and medieval lore, a more or less conscious force in the shaping of a new mythology. While in Icelandic/Scandinavian as well as Anglo-Saxon culture, rings had their mythical and worldly place, Tolkien elevated finger rings to central items and focused on their forging, exchange, disappearance, and symbolic meaning.