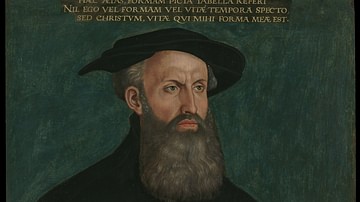

Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) broke with the Church in 1522 and defended his beliefs at the First Disputation in 1523, encouraging many people in Zürich to embrace his teachings. Among his followers was a group, soon known as Anabaptists, who felt he had compromised himself at the Second Disputation, and they were then persecuted for their convictions.

Zwingli advocated for rejection of Catholic doctrine and practice and strict adherence to the authority of the scriptures. Zwingli's 67 Articles, presented at the First Disputation at which he denounced the Church as unbiblical, inspired a number of his adherents to take his claims to their natural conclusion that the Bible should be understood literally as God's word and its precepts followed faithfully without picking and choosing only what suited one's interests. When the Bible stated, "Thou Shalt Not Kill", they claimed, it meant a Christian should not take the life of another no matter the circumstances and, further, since there was no mention of infant baptism in the Bible, this practice should be rejected in favor of adult baptism. Zwingli rejected both of these challenges.

At the Second Disputation of 1523, Zwingli compromised on a number of points including infant baptism, alienating some of his more ardent supporters including Conrad Grebel (l. c. 1498-1526) and Felix Manz (l. c. 1498-1527) who formed their own Christian community, the Swiss Brethren, notable for their practice of adult baptism. Their opponents, who included Zwingli, called them Anabaptists (rebaptizers), and considered them dangerous radicals as they refused military service, denounced tithes, and challenged both civil and ecclesiastical authority.

When the city council of Zürich condemned them through a mandate, and when four of them were executed as heretics in 1527, including Manz, Zwingli made no objection. He had already spoken out against them as extremists who threatened the success of his movement, and he seems to have been relieved when the Anabaptist community left Zürich after the executions. Their exodus was only the beginning of the Anabaptist reform movement, however, which continued to spread throughout Europe despite severe persecution from religious and secular authorities. The Anabaptist sect went on to influence the development of others still practicing today, including the Amish and Mennonites.

Disputation & Division

Zwingli began his reform movement in 1519, as soon as he was appointed the people's priest of the Grossmünster (Great Church) in Zürich, by rejecting the Church's liturgy in Latin and reading from the Gospel of Matthew in the vernacular while interpreting and commenting on it. This encouraged members of his congregation to form their own Bible-study groups, which met in members' homes and applied Zwingli's teachings to interpret scripture.

In 1522, Zwingli broke with the Church over an event known as the Affair of the Sausage, when some members of his congregation (with Zwingli in attendance) broke the Lenten fast and the prohibition on eating meat by serving sausage at dinner. Zwingli defended this practice, denouncing Lenten fasting – and Lent itself – as unbiblical. He defined his stand in two sermons, Regarding the Choice and Freedom of Foods and On Rejecting Lent and Protecting Christian Liberty from Man-Made Obligations, and then further clarified his views through his 67 Articles delivered at the First Disputation with Catholic delegates in January 1523.

Zwingli's stand at the First Disputation inspired his more zealous supporters to fully embrace his call for the supremacy of biblical authority over any other, ecclesiastical or civil, and the Bible study led by Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz began advocating for a radical revision of Christian practice completely in accordance with scripture. Scholar Randolph C. Head comments:

Zwingli's sermons unleashed powerful responses from his audiences, which included Zurich's population, rich and poor, and clergy and laity from the surrounding areas…the broad (though by no means unanimous) support Zwingli's movement enjoyed by 1525 suggests many listeners found his sermons persuasive. Zwingli's impact was amplified by a number of Bible-study circles that formed in Zurich, whose participants often became proselytizers for increasingly bold reform projects. (Rublack, 170-171)

Although Zwingli had inspired this movement, he rejected their proposals as too extreme. At the Second Disputation in 1523, Zwingli completely rejected the views of Grebel and Manz and compromised on various issues with the Zürich city council. Head notes, "among the most pressing issues were clerical celibacy, the use of images in ceremonies, and the economic obligations of the laity to the church, especially tithes" (Rublack, 171). Zwingli agreed with Grebel and the others on the first two points but not on tithes, and he also rejected their claim that infant baptism was unbiblical and condemned them as dangerous rebels.

Grebel, Manz, and others in their circle, including George Blaurock (l. c. 1491-1529), felt betrayed by Zwingli and formed the Swiss Brethren, a counter- – and more extreme – reform movement to his own. Zwingli met with them in 1524 to reconcile, but no compromise could be reached. In response, Zwingli published his sermon Whoever Causes Unrest, denouncing the new movement as divisive – the same charge the Catholics had brought against Zwingli at the First Disputation – and this led to another disputation in early January 1525 to resolve the issue. Zwingli won this debate as he had the others, especially on the point of infant baptism. The city council then issued a mandate that anyone refusing to have their babies baptized must leave the city.

Anabaptists & the Mandates

Zwingli had rejected the sacraments of the Church save baptism and the Eucharist, which he claimed as valid in that they represented one's commitment to the Christian community. Zwingli denounced the Church's claim that baptism washed away one's sins, noting that the Bible made it clear that Jesus Christ's sacrifice on the cross had taken care of this. When one had one's child baptized, one was making a profession of faith and setting an example which one's children would then follow. Adult baptism was a rejection of Christ's sacrifice and an affront to God, he claimed, in that one was claiming power over the remission of sin and, further, that the act of adult baptism was pointless as one had already been baptized into the faith as an infant.

The new group claimed Zwingli was betraying his own claims of absolute biblical authority in that there was ample evidence of adult baptism in scripture from John the Baptist's ministry to the baptism of Jesus Christ by John and the apostles' baptism of adults in the Book of Acts. This claim was countered by the argument that these examples did not support adult baptism at the present time because John's ministry and Christ's baptism happened before the crucifixion while the baptismal activities of the apostles were an act of welcoming one into the Christian community. As Grebel, Manz, and the others were already Christian, there was no need for them – or any other – to be rebaptized. The group was derisively referred to as Anabaptists, and their claim for the biblical support of adult baptism was dismissed.

Grebel and the others refused to recognize the legitimacy of the mandate and, on 21 January 1525, performed adult baptisms at Felix Manz's home and encouraged others to refuse to have their infants baptized. The city council then issued another mandate decreeing anyone not complying with the first one would be arrested and heavily fined. The Anabaptists responded by reasserting their claims, and a number were arrested including Blaurock and Manz. Grebel, meanwhile, was in communication with other reform movements elsewhere, trying to win support for their cause. He framed their struggle in biblical terms, claiming martyrdom was preferable to compromise in that Christ himself had foretold that his followers must suffer for their faith:

If you therefore have to suffer for it, you know well that it cannot be otherwise. Christ must suffer still more in his members. But he will strengthen them and keep them firm to the end. (Gregory, 202)

Zwingli continued to preach against them and the civil unrest they were encouraging, as he believed that his vision of Christianity was true, complete, and all-embracing while the Anabaptists' views were unbiblical, exclusionary, and divisive. It should be noted, again, that these charges were similar or identical to those made by the Church against Zwingli's own reform movement. The city council attempted to reconcile the two in November of 1525 through another disputation held at the Grossmünster, but, as neither side would listen to the other or make any gesture toward compromise, nothing more was accomplished than at the event in January.

Manz & Sattler

As tensions grew in Zürich between Zwingli's followers, Catholics, and Anabaptists, the city council felt compelled to issue another mandate, on 7 March 1526, this time decreeing adult baptism a capital offense:

Henceforth in our city, territory, and neighborhood, no man, woman, or maiden shall re-baptize another; whoever shall do so shall be arrested by authority and, after proper judgment, shall without appeal be put to death by drowning. (Kottelin-Longley, 184)

The city council justified its mandate in that adult baptism was the manifestation of a belief that encouraged people to defy civil authority and abandon their civic responsibilities of paying taxes and serving in the armed forces. Their pacifism, it was claimed, benefited the enemies of Christianity – notably the Turks – and their refusal to take up arms amounted to treason. In his youth, Zwingli had also advocated for pacifism after witnessing war first-hand as chaplain to a troop of mercenaries but now tacitly agreed with the city council.

Grebel had left Zürich in 1525 to preach the new vision in person elsewhere and win support for it while Manz remained and, in defiance of the March mandate, continued to baptize adults. He was arrested and, in January 1527, executed. Scholar Margot Kottelin-Longley comments:

Felix Manz became the first Anabaptist martyr in Zurich in January of 1527. Manz was drowned in the following manner: he was first trussed and taken by boat to the middle of the River Limmat, which runs through Zurich. A preacher at his side spoke kind words to him, encouraging him to recant. But then Manz perceived his mother, Anna Manz, with some other Anabaptists on the opposite bank, admonishing him to be steadfast in his faith. He did not recant, so he was heaved overboard. He sang with a loud voice, "Into your hands I commend my spirit" as the waters closed over his head. Zwingli thought drowning a very fitting way of executing an Anabaptist. Manz was really fortunate, though, because most Anabaptists were severely tortured first and then burned at the stake. (184)

Three other Anabaptists were drowned in Zürich after Manz, encouraging the group to find a home elsewhere. Just as Zwingli's teachings had spread across Switzerland, however, so had those of the Anabaptists which mirrored many of Zwingli's precepts but took them further. Catholics and Protestants, who could not agree on anything else, were united in their hatred of the Anabaptists as divisive traitors and enemies of God. In Rottenburg, the Anabaptist leader Michael Sattler was arrested for preaching against war with the Turks, citing biblical passages advocating pacifism as a Christian ideal. According to Kottelin-Longley, his sentence read:

Michael Sattler should be given to the hands of the hangman, who shall lead him to the square and cut off his tongue, then chain him to a wagon, there tear his body twice with red hot tongs, and again when he is brought before the gate, five more times. When this is done, he should be burned to powder as a heretic. (190)

Compared to the executions of Anabaptists elsewhere, as Kottelin-Longley notes, the drownings in Zürich were mild but, even so, were dramatic enough spectacles to silence the movement there and allow Zwingli's to continue to develop without the challenges Grebel and the others had championed. Grebel was already dead, most likely from the plague, by the time Manz was executed, but his letters continued to inspire others to adopt the Anabaptist vision.

Persecutions & Kappel Wars

Zwingli's approval of the persecution and execution of Anabaptists, whether overtly through his sermons or tacitly by his silence, was a significant departure for him from his younger years when, influenced by the humanist theologian, priest, and philosopher Desiderius Erasmus (l. 1466-1536), he had condemned violence as anti-Christian and advocated for the same biblically supported pacifism the Anabaptists had preached. Once the mandate of March 1526 was put into effect, however, Zwingli seems to have completely approved of the executions, and his followers apparently followed suit. Scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch comments:

The legislation of 1526 led to four of [the Anabaptists] being solemnly drowned in the River Limmat, and radical enthusiasm in the canton of Zurich subsided as quickly as it had begun. Even though only four martyrs ever died in Zurich, this Erasmian, Zwinglian, and reformed community had thereby committed itself to a policy of coercing and punishing fellow reformers whose crime was to be too radical. (150)

Zwingli would continue on this course afterwards in advocating for war against the Catholic provinces of Switzerland as a means of conversion and starting the Kappel Wars. The First Kappel War of 1529 was never actually fought as it was halted by an armistice before hostilities began. Zwingli continued his advocacy for forced conversion but was compelled to settle for a blockade of the Catholic regions when he could win no support for war from the city council or other Protestant cantons. In 1531, the Catholic cantons made a preemptive strike on Zürich before any other conversion methods could be initiated in the Second Kappel War. Zürich was defeated, and 500 of its citizens, including Zwingli, were killed in battle.

Conclusion

Zwingli's movement lost momentum after his death, as many blamed him directly for the wars, and was only saved and stabilized through the efforts of the theologian Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575) who modified and softened Zwingli's more extreme views and depoliticized the emerging Reformed Church. When Zwingli first challenged the Church in 1522, the Catholic bishop of the region wanted him quietly dismissed from his post and sent away from Zürich. The Church had learned from their heavy-handed attempts at silencing the German reformer Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) that persecution of dissenters could popularize the dissent, and the Bishop of Constance did not want that happening with Zwingli.

Zwingli had to have been aware of this as he was a member of the city council who had the power to dismiss him, and yet he completely ignored the lesson in dealing with the Anabaptists. Although he succeeded in driving them from Zürich, they continued to gain adherents elsewhere, and their commitment to martyrdom in the name of their vision attracted more followers in more areas than Zwingli's initial efforts had. The Anabaptists eventually became one of the many Christian sects born of the Protestant Reformation and are the ancestors of the modern-day Amish, Brethren, and Mennonites, among others, who continue to practice many of the original Anabaptist tenets, including adult baptism and non-violence, the central issues Zwingli and his followers denounced and had tried to suppress.