European explorers began to probe the Western Hemisphere in the early 1500s, and they found to their utter amazement not only a huge landmass but also a world filled with several diverse and populous indigenous cultures. Among their most important conquests were those of Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean (1492-1502); Hernán Cortés in Aztec Mexico (1519-1521), Francisco Pizzaro and Diego de Almagro in Inca Peru (1528-1532), and Juan de Grijalva (1518) and Hernán Cortés (1519; 1524-1525) in Mayan Yucatán and Guatemala.

Indigenous Peoples of the Americas

The Aztec civilization was located in the Gulf Coast Plains of central America and the high reaches of the Sierras. Their empire was a confederation of three huge city-states established in 1427: Tenochtitlan, the capital located on an island near the western shore of Lake Texcoco in central Mexico, Texcoco in the central Mexican plateau, and Tlacopan in the Valley of Mexico on the western shore of Lake Texcoco.

The Incas were found in the Andes and coastal regions of South America. Their empire arose in the early 13th century and was the largest kingdom in pre-Columbian America, with its capital at Cuzco, in modern-day Peru. The Inca civilization controlled a large portion of western South America through conquest and the collection of tributes from client states.

The Maya civilization had once ranged across southeastern Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, and the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador. When the Spanish arrived, the Maya civilization was well past its golden age (250-900 CE) but still had a significant presence in the Yucatan Peninsula and the highlands of Guatemala.

The Taínos and Caribs were widely distributed across the Greater and Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean Sea. These societies did not have a centralized government but were ruled by a myriad of regional hereditary chiefs and noble classes. At the time of Columbus' arrival in 1492, there were five chiefdoms of the Taíno civilization in Hispaniola, each led by a principal cacique (chief) to whom tribute was paid.

The Tupi-Guarani inhabited the Amazon rainforest and most of Brazil's coast. Like the Taíno, the Tupi-Guarani had no central government but were divided into thousands of tribes, each numbering from 300 to 2,000 people. In 1500, the Tupi numbered about 1 million people, nearly equal to the population of Portugal.

Agriculture of the Pre-Columbian Americas

The Europeans discovered that these societies were growing crops that were totally alien to them. In fact, two completely different crop assemblages had been domesticated in the Old and New Worlds. The Amerindian farmers grew cassava, maize, potato, beans, squash, tomatoes, and chili peppers, while the Iberians cultivated wheat, barley, cabbage, onions, garlic, and carrots.

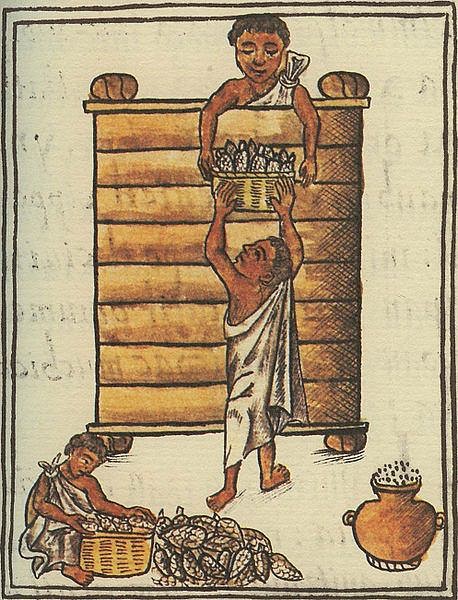

The Europeans also found that the agriculture of the Americas was just as organized and productive as theirs. The Tupi-Guarani practiced a simple swidden (slash-and-burn) agriculture that was rain-fed. The Inca utilized terraces in the mountains and irrigation networks in the valleys and plains. The Taíno raised their crops on large mounds called conuco. The Incas transformed their landscape with terracing, canals, and irrigation networks. The Aztecs built irrigated terraces on the mountain slopes and chinampas or floating gardens on the freshwater lakes surrounding their capital city. The Maya used the milpa crop-growing system, where fields were cropped for two years and then were allowed to revegetate for eight years with useful native volunteers.

The Spanish Conquest of the Americas

Columbus was the first to reach the Americas in 1492, and to his dying day, he was sure he had found Asia. Unlike the conquistadors in Spanish America who followed him, he made no large-scale conquest of the indigenous Taíno people. Instead, he established a settlement at La Isabela, in today's Dominican Republic, from which he explored the interior of the Island for gold and silver and imposed a brutal tribute system on the local Taínos. The Taíno were sent out to pan for gold on the islands, and they were expected to produce food for the colonists. He also introduced European crops and livestock “to acclimatize the European population to the new lands and open a space for the cultivation of cash crops intended for European consumption" (Paravisini-Gebert, 11).

Hernán Cortés invaded the highly structured Aztec Empire of Mesoamerica with the aid of many indigenous allies. At that time, the Aztec Empire was a fragile confederation of city-states, and the Spanish were able to convince the frustrated leaders of the subordinate states and one unconquered one (Tlaxcala) to join them. Following an earlier expedition through the Yucatán led by Juan de Grijalva, Hernán Cortés began his campaign against the Aztec Empire in 1519 and with his coalition army captured the emperor Cuauhtémoc and the capital of the Aztec Empire, Tenochtitlan in 1521. The Spanish then campaigned against the Maya of the Yucatán Peninsula and Guatemala, the Tarascans (Purépecha) of northwestern Michoacan, and the Chichimec in northern Mexico.

The war of the Spanish against the mightiest empire in the Americas – the Inca of the Peruvian highlands – was a long and protracted affair. It began when Francisco Pizarro, with his Andean allies captured and strangled Emperor Atahualpa in 1532, but it did not end for another 40 years until the last Inca stronghold of Vilcabamba (1500 m northeast of Cuzco) was conquered in 1572. The Spanish were greatly aided by a civil war between the supporters of Emperor Atahualpa and his brother Huáscar and the help of several indigenous nations that had been historically repressed by the Incas.

Organization of Spanish America

Following Cortés' conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Crown of Castile established the Kingdom of New Spain, which covered a huge area including what is now Mexico, much of the American Southwest in North America, Central America, northern parts of South America, and the Philippines. New Spain was made into a kingdom rather than a colony, as the king wanted to maintain his sovereign right and total ownership. On 12 October 1535, the Viceroyalty of New Spain was created by royal decree to serve as the king's deputy. The first viceroy was Antonio de Mendoza y Pacheco. The capital of the new kingdom became Mexico City, built from the ruins of Tenochtitlan. The Spaniards built palaces and churches there in their own style. All the old buildings and temples belonging to the Aztecs were destroyed, and the building materials were reused in the construction of the new colonial city.

In Peru, the Spanish crown first awarded the conquistadors with adelantados, giving them the right to rule the region they conquered. South America was essentially divided into strips, including the Governorates of New Castile (1529), New Toledo (1534), New Andalusia (1534), and the Province of Tierra Firme (1539). In 1542, these were reorganized into the Viceroyalty of Peru, containing modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America. It was governed from the capital of Lima. King Charles named Blasco Núñez Vela Peru's first viceroy in 1544, but it was not until the fifth viceroy, Francisco Álvarez de Toledo (1569-1581) that Peru became well organized.

The Spanish Colonial Economy

To govern their New World lands, the Spanish organized colonists and native people into two distinct social orders or republics – Spaniards and Amerindians. The Spaniards would supervise the land, run the mines, and staff the colonial administrations, and the Amerindians (la republica de los indios), would provide the labor to feed, house, and clothe the Spanish. In return, the Amerindians were to receive military protection and instruction about the 'saving grace' of the Christian faith.

The Spanish enforced this system of stratification through three institutions:

- requerimiento

- encomienda

- repartimiento

When soldiers first encountered the native peoples, they were supposed to read aloud in Spanish the requerimiento, which told the natives they had to submit to the authority of the Spanish crown or face the sword. When some semblance of control was obtained, royal authorities then gave hereditary ownership of the native land to nobles and officers who, through the encomienda, received tribute and labor from the Indian villages.

The encomiendas included all the indigenous cities, communities, and families that resided therein. The indigenous occupants were required to provide a tribute of anything the land proved to hold – gold, crops, foodstuffs, and animals, and they owed a portion of their time to work on plantations or in mines. In return, they were to be protected and converted to Christianity.

The encomienda system was thinly disguised slavery, and most owners did everything in their power to strip the natives of their culture and worked them to the bone. The Amerindians were often forced to choose between fulfilling quotas and starving to death or not making the quotas and suffering from the often-lethal wrath of the overseers. The Spanish crown passed laws to make it clear that the indigenous people were not meant to be slaves and were in fact Spanish subjects with certain rights, but these laws were met with great hostility and resistance.

In a major reform in 1542, known as the New Laws, encomendero families were restricted to holding the grant for two generations rather than in perpetuity, eliciting a huge cry. The widespread protest forced the crown to back down for a while, but in the early 1600s, the king replaced the encomienda with the repartimiento, where government officials (corregidor de indios) took over regulating the labor of the indigenous people. The Amerindians were drafted to work for cycles of varying lengths of time on farms, mines, workshops, and public projects.

In the 17th century, another agricultural system appeared, called the hacienda. Some have argued that haciendas evolved from the encomiendas, but in the haciendas system, land was granted to private individuals, but instead of the owners utilizing forced labor on these estates, free labor was recruited on a permanent or casual basis. Over time, these haciendas became secure private property and survived the colonial period into the 20th century.

The Portuguese Colonization of Brazil

The emergence of a Portuguese Empire in the Americas came about much differently than the Spanish one. The Portuguese initially saw Brazil as more of a trading post than a place to colonize, as they were already heavily invested in the Indian Ocean trade. Instead of sending large military campaigns to conquer the indigenous people, they occupied themselves with trade with native Brazilians and battling with rival groups, primarily the French. The native Tupi were viewed more as an indigenous labor force than a civilization to be conquered. The Tupi were far less hierarchical and organized than the Aztecs, the Incas, and the Maya and offered no great civilization to conquer and subjugate.

To colonize Brazil, the Portuguese crown first tried a system of hereditary captaincies (Capitanias Hereditárias), which had previously been used in the Portuguese colonization of Madeira. These captaincies were given by royal decree to private individuals, including merchants, soldiers, sailors, and petty nobility, to save the royal government the expense of colonization. The captaincies were granted control over huge strips of land and all the indigenous people that resided upon it, much like the Spanish encomiendas. Between 1534 and 1536 King John III divided Brazil into 15 captaincy colonies, which he awarded to anyone who wanted one and had the means to administer and explore them.

Of the original 15 captaincies, only two prospered, Pernambuco and São Vicente. The others failed due to resistance from the indigenous people, shipwrecks, and internal squabbles among the colonizers. Pernambuco, the most successful captaincy, belonged to Duarte Coelho, who founded the city of Olinda in 1536 and set up sugar factories and plantations, to satisfy the growing sweet tooth of Europe. Sugar production in plantations became the main Brazilian product for the next 150 years. The captaincy of São Vicente, owned by Martim Afonso de Sousa, also started producing sugar, but its main economic activity became the selling of slaves.

Because of the failure of most of the captaincies and the continued menace of French ships along the coast, King John III of Portugal (r. 1521-1557) decided in 1549 that he would have to colonize Brazil as a royal enterprise. He sent a large fleet captained by Tomé de Sousa to Brazil to establish a central government in the colony. Sousa began by founding a capital city, Salvador da Bahia, in northeastern Brazil, in today's state of Bahia. Tomé de Sousa also worked to repair the villages and reorganize the economies of the old captaincies and spread the Catholic faith among the indigenous people through the Jesuits, officially supported by the king.

Like the Spanish colonists, the Portuguese who emigrated to Brazil were looking for land and an easier life. They did not intend on doing manual work themselves and expected the indigenous people to do their work for them. When the Portuguese began to colonize Brazil in the early 1500s, they first set out to subjugate the local Tupi to work in their mines and harvest their fields. They did this in two ways. Jesuit missionaries tried to convert them to Catholicism and recruit them to live in colonial villages to work the farms. Expeditions of adventurers called bandeiras also enslaved thousands of Tupi as they pushed towards the interior searching for precious metals and stones. The Church had ruled that any 'savages' that refused to be converted to Christianity could be sold as slaves.

The Tupi proved to be poorly adapted to the routine, sedentary lifestyle of farming and were particularly uncooperative slaves. They were also very subject to western diseases and found it relatively easy to run away and hide in the dense forest. The Portuguese solution to this labor problem was to turn to African slavery, a system they had already employed in their Atlantic sugar plantations off the coast of Africa. By the mid-16th century, African slavery predominated on the sugar plantations of Portuguese Brazil, although the enslavement of the indigenous people continued well into the 17th century.

Impact of Iberian Conquest on the Americas

During the European colonization of the Americas, the Europeans did all they could to ignore the agricultural achievements of the Amerindians and set out to replace the indigenous agro-ecosystems with their own crops and methods. In this endeavor, they met with only limited success and found that their crops were often poorly adapted. Still, their populations burgeoned as they determined by trial and error which of their traditional European crops could be grown in their New World environs and which of the indigenous crops should be incorporated into their agricultural repertoire.

The encomienda and hacienda systems had devastating effects on the indigenous people and their way of life. The Amerindians were confronted with an array of crops of which they had no experience and were left with insufficient time to grow their own crops while tending the fields of their masters or working in dank, dark mines. Many starved or were worked to death, leaving large swaths of traditional plantings untended.

Amerindian numbers were also decimated by disease. The Europeans brought measles, smallpox, influenza, and the bubonic plague across the Atlantic with terrible consequences for the indigenous populations who had never been exposed to these diseases. There were at least 60 million people in North, Central, and South America before the first European contact in 1492, and by the 1600s probably 56 million had died, 90% of the whole pre-Columbian indigenous population.