Wine has been made for over 7,000 years, and effervescent wine for just as long since sealing wine before the fermentation is complete will naturally produce it. True sparkling wine, though, a wine that is clear from cloudy impurities, was invented in the Champagne region of France in the 17th century. The perfection of the method that removes the unattractive clouds which had long bespoiled fizzy wine is widely credited, rightly or wrongly, to a monk and cellar master at the Benedictine Abbey of Hautvillers, one Dom Pérignon (1638-1715). It was at this Abbey near Rheims in France that a veritable revolution would occur, which transformed the region's fortunes and changed forever the production and popularity of sparkling wine. Champagne was born. With the creation of successful houses such as Ruinart, Moët, Veuve Clicquot, and Pommery, the amber nectar would conquer all comers and become the single most famous wine in the world, a byword for elegance, celebration, and luxury.

The Long Road to Perfection

It was the Romans who introduced the vine to northern Gaul in the 1st century CE, and they were already accomplished viticulturists, fully aware of the benefits of maximising climatic and soil conditions. Pruning, grafting, and training vines were common practice, and all of these skills would be needed to grow quality grapes in the cool northern climate of the Champagne region of northeast France. It was not until the 9th century, though, that the wines of the region, still not yet truly sparkling, took off in popularity, helped in no small measure by the growing importance of the city of Rheims and its cathedral where French kings were crowned.

In the 13th century, Champagne wine acquired an international reputation thanks to the great trade fairs held annually in the region. The counts of Champagne knew that by endorsing these fairs, which sometimes lasted six weeks, and by providing trade incentives, they could encourage English, Spanish, and Italian merchants to import Champagne to new markets. By the following century, most of the area around Rheims was planted with vines. Wine had become big business.

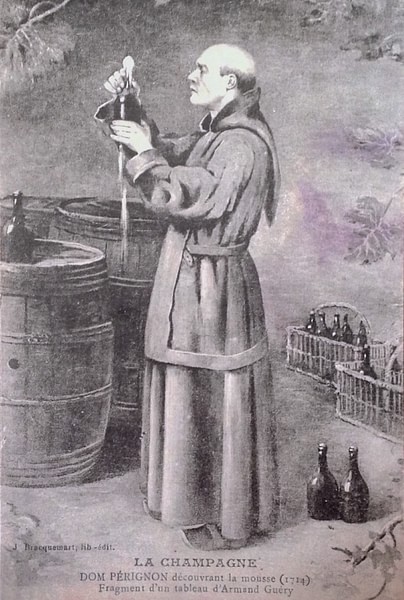

The wine being produced in the Champagne region might have been popular, but it was still the murky drink common everywhere. By the mid-17th century, though, winemakers were beginning to experiment with wine made only from white grapes and with various methods that made clearer wine, an endeavour helped by Champagne's climatic tendency to produce black grapes which only lightly colour the wine. The first attempts to deliberately produce sparkling wines were also being made, as opposed to the somewhat accidental production which resulted from winemakers trying, in fact, to avoid fizzy red wine but bottling before fermentation was complete. These two approaches would be combined by the monks of Hautvillers, amongst them one of the most famous names in world wine: Dom Pérignon.

Dom Pérignon

Dom Pérignon has acquired a legendary status as the inventor of the sparkling champagne we know and love today, but the mythology surrounding him has obscured the contributions made by those who came before and his contemporaries, both in France and England. The celebrated monk and his legendary status have also been cleverly marketed ever since Moët & Chandon bought the Abbey of Hautvillers in 1823. What we do know is that Pérignon lived from 1638 to 1715 and, following his admission into the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Vanne in 1658, he quickly impressed. Over the next decade, he acquired both the honorary title of Dom and the second most prestigious post at the abbey: cellar master. In a career that spanned 47 years, the wine this meticulous monk produced became famous not as the produce of the Hautvillers Abbey but as the 'vins de Pérignon'.

Without a doubt, Dom Pérignon was a master at blending wines from different vineyards to produce a distinctive and consistent blend, still today an essential – perhaps the essential – component of the complex process of producing champagne. Although he may not have been the one to invent true sparkling wine, indeed his brief was probably the very opposite and to try and eliminate the undesirable bubbles from red wine, the monk did speed the process along towards the drink we know today. He is credited, in a treatise written by his star pupil and successor Frère Pierre, with producing the first real still red wine. He also created the traditional champagne press, which was lighter and faster, thus reducing the time the skins were in contact with the juice, greatly increasing the wine's final clarity. Another important decision was Dom Pérignon's return to using cork stoppers which were a much better seal than the previous wood and hemp plugs, ensuring less carbon dioxide and so magic sparkle escaped from the wine. He employed stronger English glass bottles to ensure far fewer exploded from the pressure of fermentation and high cellar temperatures, the frequent nightmare of all wine producers of the period. Finally, and most important of all, he perfected the process of producing clear white wine using black grapes.

All of the key components were now in place to produce a reliable and more appealing clear and sparkling wine. By the next century, champagne production and storage would be further perfected by such legendary figures as Jean-Rémy Moët (1758-1841) and Madame Clicquot-Ponsardin (1777-1866), the widow known as the Veuve Clicquot. This and masterful marketing would ensure that champagne was ready to conquer the world.

Méthode Traditionelle: Making Champagne

Champagne has always been an expensive wine, and the reason is the extra time and effort that goes into its production. This procedure was, until relatively recently, known as Méthode Champenoise but is nowadays referred to as méthode traditionelle. As we have seen, the long and meticulous method took centuries to perfect, but by the 19th century, the techniques were in place which would be religiously adhered to thereafter and which continue to distinguish champagne from its less illustrious competitors.

Wine with the right to carry the name 'champagne' is exclusively produced in the Champagne region of northeast France. The grape varieties used are the black grapes Pinot Meunier and Pinot Noir, and the white grape Chardonnay. The particularities of the region – vine-friendly hills, cool climate, sufficient but not excessive quantity of rainfall, excellent drainage, and chalky soil – make the environment, or terroir, of Champagne ideal for the production of sparkling wine.

When the grapes are harvested, usually in October, the grape pulp (marc) is gently squeezed in presses and the resulting juice is called the must. The first juice squeezed from this pulp is the best, known as the cuvée, rich in sugar and acids. The next pressing extracts a murkier juice called the taille, as the skins, pips, and stalks discolour it. The juice is then allowed to ferment for up to ten days in large vats, typically of stainless steel but sometimes of oak. Then, in the case of non-vintage champagne, the juices of different sources and years (perhaps as many as 40) are expertly blended in a process known as assemblage, which gives the wine of a champagne house its unique character. A fining of the wine is achieved by adding a substance, such as gelatine or clay, which attracts remaining impurities, and these then settle to the bottom of the vat. The wine is then racked, that is poured from one vat to another, perhaps several times to ensure a minimum of sediment remains. Finally, the wine is poured into bottles, which are temporarily capped.

The next step in the process, and one which begins to distinguish champagne from other wines, is to experiment with the composition of the wine inside the bottle. Adding a mix of sugar, yeast, and wine (liqueur de tirage) after the first fermentation is an age-old practice that reduces the tartness of the wine and promotes a second fermentation in the bottle to create the magic bubbles. A more modern technique, first employed in 1801, is to add sugar to the must during pressing (chaptalisation), thus ensuring that during fermentation more alcohol will result. An important legal regulation here is that the bottle in which the second fermentation takes place is the same as the champagne bottle the customer eventually buys.

(F. Scott Fitzgerald,The Great Gatsby)

Adding sugar can be very risky, though, as too much might burst the bottle, and too little might not create the desired level of fizz. Indeed, since antiquity, wineskins had been bursting prematurely because of the pressure built up by the wine continuing to ferment in storage, and early glass bottles fared little better in keeping the valuable drink safe until required. The problem was that wine was bottled or stored in the autumn, and the fermentation was very often not quite finished. Winter would interrupt the process where the yeast cells in the wine converted the sugars to alcohol but, come the warmer temperatures of spring, the yeast would resume its work – the second fermentation or prise de mousse. With this second fermentation came the agreeable by-product of additional bubbles in the form of carbon dioxide, but what was less desirable was the increase in pressure, which made the wine either burst its weak glass container or simply escape if stored in wooden casks. What was needed was stronger glass and, on top of that, a more secure way of closing the bottle. A partial solution came with the invention of thicker glass in England and corks secured by a cord.

Another aid was science. In 1836, a French chemist called Jean-Baptiste François invented a scale to measure how much sugar should be added to the tirage to produce the desired amount of sparkle yet not create too much pressure within the bottle (6 atmospheres is the ideal nowadays). With better glass and more control on the liqueur de tirage, breakages fell from anything up to 90% in disastrous years to a much more acceptable loss of 8%. No longer did spilt champagne have to be made into vinegar, and visitors to the cellars need no longer wear fencing masks to protect themselves from unexpected explosions.

When ready for the prise de mousse, the bottles are piled in their thousands in the deepest parts of the chalk cellars of Champagne. The cooler the storage temperature (10-12 Celsius), the slower the fermentation process, which then creates the most sophisticated flavours and smaller bubbles of the finest Champagnes. The bottles are then left for several weeks or even months. After this time they are transferred to sloping boards, or pupitres, with each bottle placed in a hole at 90 degrees. Then, over the coming weeks, each bottle is turned every day in the process known as remuage. Each day the bottles are turned a mere eighth of a revolution and nudged a little downwards. This helps to prevent the sediment which results from the fermentation from sticking to one area of the bottle's interior and to move it towards the neck. After the legal minimum of 15 months, the more ordinary non-vintage champagne is now ready for the sediment to be removed, but finer wines are left in storage for much longer, vintages for at least three years and the prestige champagnes for 10 years or more. Placed vertically upside down (sur pointes) these prestige bottles will mature further and develop both a richer flavour and bouquet.

The clarity of the finished wine is greatly improved by the last stage of the process: dégorgement. Wines had long been stored neck down in sand so that sediment produced during fermentation within the bottle settled in the neck. Then, when ready for drinking and at the moment of removing the stopper while the bottle was turned downwards, the bottle was quickly jerked upright to ensure only the portion heavy in sediment escaped. This trick, known as dégorgement à la volée, was satisfactory when the champagne bottle was in the hands of an expert but not much use to the casual drinker. Someone, exactly who is not recorded, then hit on the idea that by topping up the bottle with clear wine and sugar (liqueur d'expédition) and re-corking it after removing the sediment meant that the wine could be opened by anyone without any fancy wrist movements. In a final step towards perfection, a new and more efficient method of dégorgement was invented in 1884 where the bottlenecks were dipped in freezing brine. In dégorgement à la glace, the sediment is thus semi-frozen and made easier to remove. In addition, because the wine is at a lower temperature, less gas is lost in the process compared to previous methods. With the sediment removed and the bottle topped up, the champagne is now, at last, ready to be labelled and corked, with a metal cap and cage (muselet) added to ensure the cork remains in place.

Conquering the World

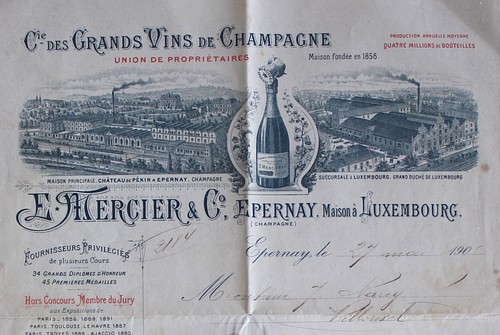

By the end of the 18th century, and still not yet known as champagne, the vins mousseux of the Champagne region was growing in popularity, especially amongst the aristocracy of England. To meet this demand, new houses were establishing themselves including Ruinart (founded 1729), Chanoine Frères (1730), Forrest Fourneaux (1734 and now Taittinger), Moët (1743), Delemotte (1760 and now Lanson), Dubois Père & Fils (1770 and now Louis Roederer), Clicquot (1772), and Heidsieck (1785). Many of these companies had sprung up as secondary enterprises connected to the hugely successful Rheims textile industry. The cloth barons had helped spread the name of Champagne's wine by offering freebies to their clients, a practice which soon developed into specific orders.

By the early 19th century, the techniques of dégorgement and liqueur de tirage ensured the wine was suitably clear and sparkling, but what was now needed was a convincing marketing strategy to ensure wine-lovers worldwide would pay premium prices for the pleasure of drinking it. In addition, the Champagne producers needed to guarantee that the wine arrived at its final destination in the same condition in which it left the vineyards. One figure, in particular, would introduce innovations that finally made Champagne production a hugely profitable business: Madame Nicole Barbe Clicquot-Ponsardin. Losing her husband and partner to typhoid fever, the widow Clicquot would overcome the obstacles of wars, trade embargoes, and the fragility of her product to match and beat her competitors in the male-dominated wine industry.

Madame Clicquot had pioneered the trick of remuage by inventing a board with holes in which bottles could be placed at an angle using her wooden kitchen tabletop. She insisted that her glass suppliers provide her with taller more elegant bottles, and purchasing 65 million over the years, she got what she asked for. Aside from these practical innovations, the widow was an accomplished and daring entrepreneur. Audaciously ignoring a ban on importing champagne to Russia at the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), Clicquot sent two shipments of her fabulous 1811 vintage, around 23,000 bottles, and thus cornered one of the most important markets in the world. Veuve Clicquot Champagne, the favourite of the Tsar himself, became a byword for luxurious elegance. Jean-Rémy Moët might have long benefitted from the favours of his close friend Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), but it was Clicquot that was now taking Europe by storm.

(Napoleon Bonaparte)

Challenges & Protection

In the second half of the 19th century, another widow, Jean Alexandrine Louise Pommery, aimed her sights at the burgeoning English market and pioneered the now-common drier brut Champagne to meet the preferences there, although the fashion was still to drink it as a dessert wine and not as an aperitif, as today. Competitors soon followed in the widow's wake, and the wine of Champagne, produced increasingly on an industrial scale but still with personalised attention, became truly big business. Five million bottles of champagne were being sold each year in France alone. Three or four times as many bottles were sold abroad.

There were challenges, too, like the Phylloxera pest that blighted vines across the region in the first decade of the 20th century. This disaster necessitated the grafting of American vines onto French ones; some connoisseurs said champagne was never quite the same again. But by now champagne was popular with everyone, and the Jazz Age of the 1920s and 1930s witnessed tens of millions of bottles being consumed each year. Champagne was firmly established as the luxury drink, with a bottle costing as much as the equivalent of two days' pay for a labourer. Champagne was being drunk to celebrate life events, it made parties swing, sports winners splashed it on their adoring fans, and ships were seen off with it to embark on their maiden voyages.

The success and popularity of champagne over the following decades despite economic depressions and wars was such that imitators soon sprang up producing cheaper and inferior wine appearing in bottles labelled almost exactly like those from real Champagne houses, but with small variations of spelling. The fightback began with the formal establishment of the Syndicat du Commerce des Vins de Champagne in 1884, which represented 61 houses and protected the region's exclusive right to produce champagne. A second syndicate was created in 1912, the Syndicat des Négociants en Vins de Champagne, and the two formed a union in 1945. The 'champagne' name has been vigorously defended against all comers from winemakers to perfume manufacturers ever since, and its position as the world's most famous wine seems assured for many generations to come.