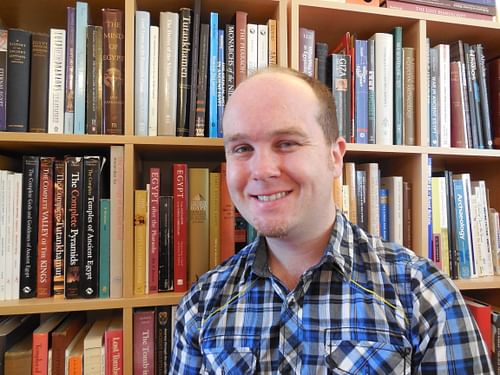

World History Encyclopedia is joined by Egyptologist and author Garry Shaw to chat about his new book Egyptian Mythology: A Traveller's Guide from Aswan to Alexandria.

Kelly (WHE): Do you want to start with telling us what the book is about?

Garry Shaw (Author): Absolutely! So, it is a travel mythology, which is quite unusual. It starts with a journey beginning in the south of Egypt, which is the traditional border in the region of Aswan, and then you travel northward to the Mediterranean Sea, stopping at various locations along the way, which have religious importance or a lot of mythology behind them. That is the basic gist of it, and it is quite a fun, different approach to Egyptian mythology than what you normally find in many of the books.

You will find that many books on Egyptian mythology talk about it in a sort of thematic way, a chapter dedicated to this subject, then another subject. Whereas in this version, we can approach it in a slightly different way by looking at the locations, we can focus on the gods of those locations, the mythology that surrounds those particular gods, and the festivals or some of the rituals. Then we progress to different cities and towns, looking at these different kinds of beings and the beliefs surrounding them as we move along. It is designed to be interesting not just to people who are travelling but also to armchair travellers. If you want to learn a bit more about Egypt, the locations, and the gods, it is great whether you are on a cruise in Egypt at home. Hopefully, this different way of approaching the subject makes it a bit more immediate, a bit more exciting, a bit more as if you are on the journey. I am hoping that people will really enjoy it because it is a bit different.

Kelly: It was a wonderful new way to read about mythology. How did you go about making travel and mythology mesh? Was it difficult?

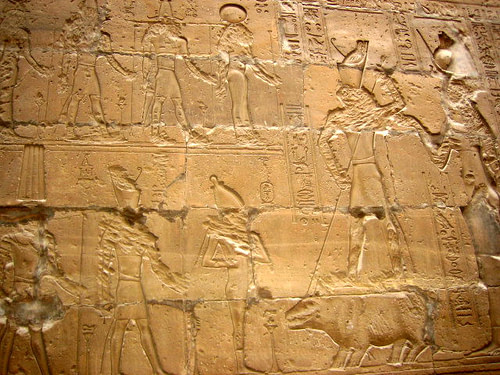

Garry: I think I got lucky because Egyptian mythology lends itself very nicely to a travel-themed mythology book in this way, simply because different locations around Egypt have different gods. You might go to one town or city, and they had a god that was the specific focus of their attention of the temple in that town. Then you might travel a little bit further north, and there is another town with a different God. And so, it creates the structure for you if you are doing a journey. For example, there is the town of Edfu, which is in the south of Egypt, and the god that is focussed there is Horus. There is a lot of mythology around the god Horus because he is incredibly important in the Egyptian pantheon. Every king was seen as an incarnation of the god Horus. So, in this location, you have him, and I can talk not only about his mythology in general but also the specific mythology associated with the area of Edfu because that was his a major area of worship.

There is also this fabulously, amazingly well-preserved temple there dedicated to him, which is a major tourist attraction. People travel there to see this temple, and it already kind of creates the structure for me. So, I can begin that chapter talking about myself visiting this location. I have been there, I can picture it, I can describe it. Then I can talk a bit more generally about who is Horus; it is important to set the background. Then I can talk a bit more about the more specific mythology and legends connected with this temple. I try to follow the same pattern in the different chapters. This is just following the Egyptians themselves and the way that their religion was differing across the country, depending on the gods of the different towns and cities.

Kelly: I think the two biggest things that struck me when I was reading were the amount of variation in myths throughout Egypt and how many of the Egyptian gods change.

Garry: The Egyptian gods do change depending on the location. You might have a myth of one part of the country that has a certain god in the lead role, and you might have the same myth in a different part of the country with a different god doing that role. There was no real kind of set myth. These things changed according to location and time, and they switched around the gods that were involved in these stories. So that leads to all these variations, and of course, we are dealing with often fragmentary material that is spread over thousands of years. Obviously, these myths evolved as the stories were told by different people at different times. Even some quite fundamental parts of Egyptian mythology have variations, too, depending on the location. This book gave me the chance to write about some of the things that you might normally skip over in a general book. The locations almost force you to talk about some of these variations because they are one of the major myths of that location.

It is quite well known that the Egyptians had strong beliefs surrounding the sun god and his power. He was a creator, one of the most important gods, and very visible, obviously, in a place like Egypt where the sun is always present. The traditional myth, to put it very straightforwardly, is that the sun god was reborn in the morning, he would rise over the eastern mountains across the sky in a boat sailing because the sky, the blue sky was regarded as water. He would sail across the sky and then set as an old man on the west behind the western mountains. He aged over the course of the day and then entered an underworld which the Egyptians called the Duat. He passed through this realm, got regenerated, and was reborn. This is an endless mythological cycle that we could all witness ourselves every day. Lots of the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings have these underworld books that talk about the sun god's journey through the night and what he gets up to. These have different variations, even within the same tomb.

Kelly: Would you say the versions of the myths that are more popular or more well-known today are the ones that have been either preserved the best or the longest but maybe not necessarily the ones that were believed by the most people?

Garry: It is a case of what has survived. Many of the myths that are popular today are ones that were preserved by the Greeks and Romans later, particularly the story of Osiris. On top of that, we look at the ancient material and we are left with what survives, what is found during excavations, and even that is very fragmentary, and you have got to piece these things together. Of course, because much of our evidence comes from desert sites, like temples and tombs, particularly tombs, there is this focus on afterlife beliefs. So, you will find a lot more about Osiris, for example. Because he is a god of the blessed dead and regeneration, he will be mentioned in every tomb. There is a lot of information about someone like him compared to some of the other gods, which might have been popular on a state level, at least.

There is also the difference between what might have been going on in the major temples and what has been going on at the village level and in a person's household where more local gods were worshipped, too. I am sure there would have been lots more stories about local gods in the village level that were never written down. We have a great insight into Egyptian religion, but it is often very much focussed on the high-level state religion in the major temples that have survived well. Sometimes that is very late in Egyptian history, which again is a focus on a particular period and not the earlier period. There are all sorts of problems when you have got to adapt and point these things out, too. I try to be clear in my books; where there are problems with the evidence, or where a story ends, or the papyrus breaks, we do not know what happens next.

Kelly: I remember quite a few times where you say this is fragmentary or we do not have this bit of the story, but we can assume that this happens. I know that you had to take things from multiple different sources to try and reconstruct the myths. This must have been such a difficult thing to do.

Garry: Yes. This has been a major focus of many Egyptologists since the decipherment of hieroglyphics. Many people have been collecting this information, and a lot of this material comes from temples and tombs, which have been studied for a very long time. I, at least, have the benefit that a lot of this stuff has already been studied, and I know where to look for the information. But it takes a very long time to look through all of this, look for the variations. There is so much detail, so much variation, so much out there that I found at the very beginning of writing this book that even though I have already written a book on Egyptian mythology, I still had to almost begin again.

Kelly: You could tell that it was really well researched, but it was incredibly easy to read. You can really feel your voice coming through. You have put in these little commentaries, which I think also gave it a light-hearted feel.

Garry: I am glad you think that because I tried to mix a bit of humour in. I think it is important; people learn better when they are enjoying themselves. I want the reader to have a good time when reading it, obviously. I am writing it for people to sit and enjoy reading it in the evening or maybe if they are on a cruise or something. I do not want them to fall asleep when reading it, and I think a few jokes help people remember certain key details, too. I think having a good voice, trying to put across a bit of personality in these things helps a lot. I wanted it to feel like someone who was telling the stories to you, addressing you, the reader.

Kelly: It felt as if you were the travel guide and we were walking at the site, and you were saying this stuff to me. It felt as if you were right there, which I thought made it really enjoyable to read compared to other non-fiction books. Did you have a favourite site?

Garry: I think there are lots of great places, obviously, but my favourite site is Saqqara, which is covered in this book in the 'Memphis and its Necropolis' chapter. In that chapter, I talk about Memphis, which was close to modern Cairo, the necropolis of that city, and the pyramids of Giza. But just south of Giza, you have Saqqara, which is another great necropolis where people were buried for thousands of years. I really enjoyed visiting that site and writing about it because there was so much going on there. It is not one of those sites that were used for a short period. You have got thousands of years of burials, different types of burials, not just human burials, but also animals. There were shafts filled with mummified animals in this location, but it is also the place where you get the step pyramid of Djoser, which is the first pyramid in history. It is the first monumental stone building, and that is really impressive! Nearby at Saqqara, you have later pyramids as well, where you have got the Pyramid Texts, which are early descriptions of the king's journey to the afterlife. There is so much you could see at this one site, I could have written hundreds of pages just about that. I really enjoy looking around and feeling awed and impressed by everything that still survives.

Kelly: It is so interesting that there are some sites that were so important in ancient Egypt but there is nothing left now. There is a site I am thinking of, but I cannot remember which one.

Garry: I think you are thinking of Pi-Ramesses, which is the great city that King Ramesses II, a very famous pharaoh, of course, Ramesses the Great, had built. Now you go there, and it is a small village called Qantir, and there is nothing to see. It is just a pair of stone feet in a field, the remains of a statue. This is not a tourist site, but the interesting thing there is that the city basically fell into disuse when the canals around it got silted up and they dragged all the major stonework to another site nearby, which is called Tanis. One of the reasons there is nothing left is because they moved the city and reused it. It is unusual being there and just seeing this is where they say a grand ancient city used to be and now it is just a very normal, very nice little village. I wanted to include that because I think Pi-Ramesses was this major city of the ancient world but it also emphasises how some things, like great temples, have been preserved and some places, especially cities and settlements, just did not last because they were often built in places where people live today. Over thousands of years, these things have gone, and you cannot really find anything without excavating or doing some ground-penetrating radar. Egypt has still a lot more to discover.

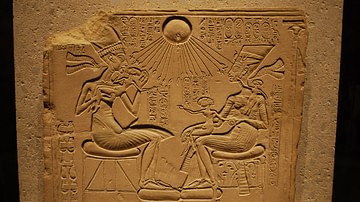

Kelly: The idea of a site being disused in antiquity makes me think of one of my favourite periods of ancient Egypt, which was when Akhenaten built his own site, and then when he died his site was abandoned. We have evidence that all the other gods were still venerated, but he brought the Aten to the very head of the pantheon.

Garry: The thing with Akhenaten is it is hard to kind of figure out sometimes what he was thinking, and people create their own theories around him. The Aten existed beforehand, but he was not very prominent. It was just a manifestation of the sun god. The Aten is basically the physical sun disc, the circle you see in the sky, and this is a manifestation of the sun god. He had been around for a long time, but he was just one you did not really find mentioned very often compared to gods like Horus and Osiris, particularly Amun, Amun-Ra, who was one of these very, very important gods in the time of Akhenaten. Even Akhenaten was born as Amenhotep. He was Amenhotep IV at the beginning of his reign, so his name refers to Amun, this important god of his time. But things very quickly change. It looks like it should be a normal reign, you have got Amenhotep IV coming along, Amun is an important state god.

He goes to Karnak to start building, and Karnak is where the major temple to Amun is. But what does he do there? He starts building a temple to the Aten instead. It begins this strange shift in Egyptian art, architecture, religion, and he quickly changes his name to Akhenaten instead, referring to the Aten and removing Amun from his name. He seems to have a particular hatred of the god Amun, Amun's name starts being scratched off everywhere, as well as other members of the family grouping of Amun, and plural references to gods also get attacked and become singular. The Amarna period is this very unusual and quite short phase in Egyptian history. Akhenaten only reigned for 17 years or so, but he did all these changes quite rapidly. It depends on how you look at it, but he was certainly attacking Amun and some of the other gods, too, removing their importance. I guess that makes sense to me because he was a king who became obsessed with worshipping a god of light, the sun disc. Amun is a god that represents the hidden and he is worshipped in darkness in a little sanctuary at the back of the temple, like many Egyptian gods. So, if this is a god of hiddenness, he is pretty much almost the opposite of what you would find of a sun god.

It makes sense that he would be attacking that god because there are others he left alone. Then he created this city, Tell-el-Amarna, and it was a short-lived city that basically was made from scratch in a place where people had not really built before. It was a new city dedicated to the Aten, and they built it very quickly. Multiple palaces, a grand temple, a smaller temple to the Aten. They started cutting tombs, including a royal tomb in the cliffs on the eastern side, which is the opposite of where they would normally build tombs. You normally build tombs in the west because that was the direction of death. He built the tombs on the east side in the direction of the sunrise. He started making different styles of art, started composing – as far as we can see, it might have come directly from the king – these hymns to the Aten. It seems people were still allowed to continue with the household religions. It does not seem like this was a complete ban on the traditions. It just seems, on a state level, there were certain gods he wanted to get rid of.

Amarna was never really used again after Akhenaten died because everybody went back to the old ways. So, this phase ended quite quickly. Eventually, everything got covered in sand, but the foundations are left of this entire city under the sand. It is one of the world's most important archaeological sites, and it is important because it shows a snapshot of this time in Egyptian history. It gives you insights into these changes that were going on and how life was in this city under this quite unusual king. I tried to explore a bit about this in the chapter about Tell-el-Amarna to try and create a balance. I talk as much about what remained the same as what changed under him to try and present some of this different information so that people can judge for themselves how revolutionary he was. Hopefully, people will enjoy reading that section, too!

Kelly: It is all so fascinating! Thank you so much for joining me today!

Garry: Thank you very much for having me here!