World History Encyclopedia is joined by Jennifer Saint, who is going to tell us all about her debut novel Ariadne.

Kelly (WHE): Do you want to tell us a little bit about the book?

Jennifer Saint (author): The book is a retelling of the myth that we are all familiar with from childhood, Theseus and the Minotaur, and it is from the perspective of the woman who made that happen, the woman who saved the hero, Ariadne. It tells the story of not just what happened with Theseus and the Minotaur but also what led up to that decision, what made her choose to betray her family and her kingdom, and what happened to her afterwards.

Kelly: The book is split up into four sections, and by the end of the first section, you have already seen the whole Theseus and the Minotaur happen. Did you differ at all from the primary sources you used?

Jennifer: I went primarily with Ovid's Heroides. In the 1st century BCE, he was writing these letters from mythological heroines to the men in their stories. I used Ariadne's letter and Phaedra's letter from that, and Euripides' play Hippolytus for Phaedra's story. I did depart from the myths quite a bit. The Heroides does not take Ariadne past the episode on Naxos, but it really gave me a grounding in the kind of character that I wanted Ariadne to be. In the letter, she is incredibly passionate, incredibly angry, and she has got such a powerful voice. In Euripides' play Hippolytus, she is more of a passive victim of what happens to her. Also, in the play and in other versions of her story, she makes a false allegation of rape. I wanted to tell her story in quite a different way and not perpetuate the idea that false rape allegations are a common thing because they are absolutely not.

Kelly: No, they are not. I enjoyed being able to see the thought processes from Phaedra's point of view because the play is so tragic, and I guess there are a couple of differences where, in the play, this is brought on by Aphrodite, but in your book, you have decided to make it a completely organic experience. Did you already want to do that when you first started writing the book or is that something that sort of came out of writing Phaedra how you wanted her to be?

Jennifer: Yeah, I mean, Phaedra really developed actually over the writing process. She became a much bigger role in the story than I originally intended her to be because I realised how important she is, and how significant she is. And although it was difficult because it would fit so well with the themes of what happens to a lot of the other women in the novel, to go with the version in which in the play Phaedra is being punished for Hippolytus' behaviour. He is arrogant, he has insulted Aphrodite, and Aphrodite decides to ruin him by making Phaedra fall in love with him, and that ruins her in the process.

That theme of women being punished for the behaviour of men is obviously so prominent throughout the book. So, it would have fit to keep that, but at the same time, in the traditional stories these characters are larger than life and they do not always behave in a way that seems psychologically convincing. When you are writing a novel, it feels like a cop-out to say a god made them do it. It does not ring as true, and it seemed to me so believable that Phaedra would fall in love with Hippolytus because she is married to Theseus, who is not a very good husband, to state it mildly; he is much older than her, and the way he treats women is horrendous. Then you have Hippolytus, who completely rejects that lifestyle, who is the opposite of his father in so many ways. So, it seems so obvious to me that Phaedra would organically and naturally be so drawn to him when he turned up, not necessarily because of who he is, but because of what her life is like.

Kelly: Definitely. I felt so much for Phaedra, and as wrong as it is, you almost get it. You fully understand why she would be feeling this way. How did you go researching it and compiling all the information? Did you find any parts difficult? Did you have any contrasting evidence and how did you work through that?

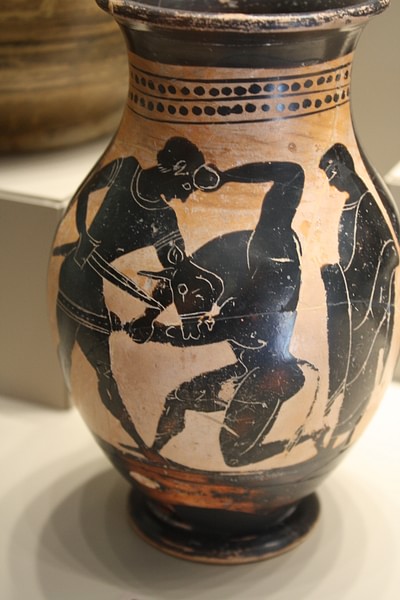

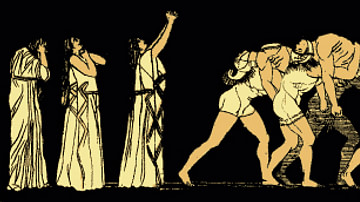

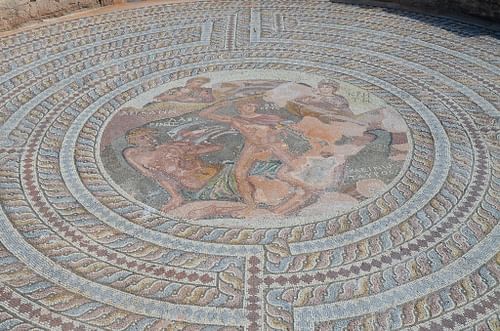

Jennifer: I started with the Oxford Classical Dictionary, which is a massive reference book. It is quite comprehensive in that it gives quite a lot of versions of what happens to these characters. But some of them do conflict. So then, as I said, I used the Heroides, I used Euripides' Hippolytus, I used Theoi.com, I looked for vase paintings, classical paintings, anything that kind of showed these characters that I could use to build a profile for them. A lot of versions of mythology contradict each other, and sometimes it is easy to pick because there are versions where Ariadne dies really early on in Naxos, so I knew that I was not going to use those versions of the myth because it would be a much shorter book.

I think particularly deciding on the ending, I departed from some of the better-known versions. The themes that stood out to me in these women's stories were women being overlooked, women suffering the consequences of men's behaviour, and women's lives being less significant than men's reputations and glory. So, when I was choosing what version of the myth I was going to go with or even to take a complete detour, it was important what fit the story that I wanted to tell.

Kelly: It is a super prevalent theme throughout the whole book, and you start from the very beginning with the mention of Scylla. I did not know Minos treated her like that. I found that Ariadne was really self-aware of this. For Phaedra, that developed as the book went, but Ariadne was completely aware of the ways that men used women and how they just did not have a say from the very beginning. It was such a prominent theme throughout the whole thing.

Your characterisation of Theseus was really interesting; he is not as much of a hero as some of the other great heroes in myth. Do you want to tell us a little bit about how you developed his character?

Jennifer: Yeah, definitely. I listen to a podcast, Let's Talk About Myths, Baby by Liv Albert, and she talks a lot about Theseus. She raised a really interesting point about him, which is that unlike other heroes in Greek mythology, he primarily kills other people, rather than monsters. I mean, he does obviously kill the Minotaur, but a lot of his victims are human. So already you see how he stands out as a darker character. A lot of the stories about him are really, really shocking and horrendous, but because he is this legendary hero of Athens, there are obviously a lot of stories that glorify him and gloss over the more unpleasant aspects of his character.

I wanted to present a more balanced version of him. I was also interested in the way that it is not just women who are trapped in this very misogynistic, patriarchal narrative. The men are trapped in it as well. In the Iliad and the Odyssey, I was always fascinated by the way that Achilleas sacrifices everything for glory, reputation, and honour, and then when Odysseus comes to him in the underworld, he says none of it was worth it. I thought there is such a tragic irony in that, and the way that these heroes just do not recognise the value of the life that they have got because they are so focussed on this concept, this nebulous idea of some kind of immortality through deed and reputation. And there is a sadness in that as well, it makes them treat other people as disposable and expendable, especially the women. I thought there were more layers to him. He was not just a hero, nor completely a villain, though his behaviour is definitely more towards the end of the spectrum.

Kelly: It is so interesting because I feel like you could have gone just all-out horrible. It probably would have been really easy to make him this deplorable character that we automatically hate, but it was an undercurrent. When you originally say he has got cold green eyes, that is not really the kind of description you associate with a hero. It was more of a calculating evil underneath this heroic exterior. Ultimately, he ends up alone and sad, so it does make you feel a little bit for him at the end, even though you do not really want to feel for him.

Jennifer: He has brought it all on himself. I think that he is so focussed on getting this glory that actually, when you look at it, is not really worth very much at all.

Kelly: No, not at all. I guess this brings us to the Minotaur himself. You had him quite human; characters like Pasiphaë and Ariadne remember that the Minotaur had a name, Asterion, and that he was half-human. They tried to raise him as human as possible. What made you want to bring out the idea?

Jennifer: I suppose that is how you would treat him as a mother. I felt really sorry for the Minotaur as well because it is not his fault. He did not ask to be born. He did not have to be a monster, and he is created as a cruel joke Poseidon plays on Minos and his family. I felt that it is not the Minotaur who was the real monster in that story; it is absolutely Poseidon for creating him. I know that there are stories that say Ariadne had a special relationship with the Minotaur. As a mother and as a sister, I think you would do your best, and this baby is half-human. It is half-monster, but you would desperately want to try and nurture any scrap of humanity within him that you could find. And I thought the Minotaur's story is such a tragedy as well.

Kelly: I agree. Is there any reason why you left Phaedra out of that? She did not want anything to do with this little baby, half-human. Is there any reason why you did not have her treat him the same way as Pasiphaë and Ariadne?

Jennifer: I think just because she is younger and less able to understand the nuances. She sees him as a monster, not a baby, not human, just something repulsive and revolting. I think not everybody who would be able to look at him and see anything different.

Kelly: He is just another example of how women are forced to deal with the repercussions of men's actions and choices. If Minos had just sacrificed that bull, none of this would have ever happened.

Jennifer: That is just what makes Greek tragedy so tragic, that it is always preventable.

Kelly: I actually found when I was reading your book, it felt a bit like a Greek tragedy. You did not get a lot of battle scenes or violence. You do not see first-hand the Minotaur being killed, but you hear about it later, and that really struck me as a Greek theatre idea. Then again with Ariadne and the catharsis when she was on Naxos. Did you have any of these ideas in advance or did they just form as you were writing the story?

Jennifer: I think not consciously, but when you put it like that, that is true! It is in there, and that is probably just from reading classics and knowing it, and that was how the story just seemed to come. Ariadne's catharsis on Naxos was incredibly satisfying to write. It really was.

Kelly: I feel like Ariadne went through so much growth in this book. Did anything that you write about her character surprise you?

Jennifer: Yeah, I think so. I suppose the magic of writing is when your characters do take on a life of their own and they do start to do things that surprise you. That is probably when you think, oh, maybe I am writing something that is good. So, her anger on Naxos did surprise me a little bit. And I suppose that is because, as a woman, you do not feel like you can express your anger, you are often socialised to push it down and to direct that anger internally at yourself. So it did feel quite different to be writing a woman just screaming out all of that rage. But of course, she is able to do that because there is nobody else there. And at that point, why not scream at the universe? That felt like a shift in Ariadne's character. I was thinking, she did this brave thing in helping Theseus, but she is going to go on and she is going to be braver, she is going to get strength from these things that happen to her, and that is going to change who she is.

Kelly: Seeing her just unleash these emotions was so wonderful because I feel like she bottled up so much. You get the whole lifespan of both Ariadne and Phaedra, from childhood to the day that they die, and they both grew up in really different ways. Were you planning on having them so contrasting as characters? I feel, especially when they both were mothers, the way that they feel about their children was so different, whereas they had a very similar upbringing. How did you work with that?

Jennifer: I was always very interested in that because their stories are told separately most of the time, even though they are sisters and they have their shared childhood, the shared experience of the Minotaur. Then, of course, their fates are interlinked with Theseus in later life. But even so, I had never come across any story, any version of their stories that brought them together. So, I was really interested to do that and to think about the ways in which they would diverge because their experiences after Crete are so very different.

Phaedra lives out what Ariadne was supposed to; what Ariadne wanted for herself is actually what Phaedra goes on to do. And it turns out so differently from how either of them could have expected. I thought that would really create the contrast in their characters, how they survive the lives that they go on to after the Minotaur really shapes who they are, their personalities, and their experience of motherhood depending on the kind of support that they have around them. You have got Ariadne on an island populated with women and you have got Phaedra, a foreigner in a city that is hostile to Crete where she is from. I thought that Phaedra, being much more isolated, would feel differently about being a mother. She would have that different relationship with her children because it was just so much harder for her.

Kelly: You brought this up at one point where she looks at one of her kids who has the jawline of Theseus. It is like having a reminder that she is locked in this life with a man she does not love. I feel like you forget that they had the same childhood and they are sisters.

Jennifer: We do not see them together very much, and Phaedra's story is usually told much later. She references the Minotaur and her upbringing a little bit in Euripides' play, but it is not such a central part of Phaedra's story, even though it would have been! Growing up with a monster that eats people would be very significant in your life.

Kelly: Yes. They have had this upbringing where they were just terrified all the time. You mentioned at the beginning of your book where suddenly they would hear a roar or the ground would shake. It is just a constant reminder that there is this monster right underneath you, and there is nothing you can do, and there is nowhere to go. You have got to assume that that is going to affect a child somehow.

Jennifer: I think so.

Kelly: As your debut novel, I think you have got a lot of traction. A lot of people are reading it, and this genre is booming right now. There are a lot of different retellings happening. Do you have any more plans to explore other myths or other women in future books?

Jennifer: Yes, I have actually finished drafting my second novel, and that is going through the edits at the moment. That is another mythological retelling from the perspective of women. I am starting a third book as well because I think there are so many stories to tell. Personally, I cannot get enough of them. So, I am really happy to be writing more, and I think there is a lot more scope for it.

Kelly: Well, thank you so much for joining me and for joining World History Encyclopaedia. It has been awesome to talk to you about your new book, Ariadne.

Jennifer: Thank you so much for having me!