Scylla and Charybdis were monsters from Greek mythology thought to inhabit the Straits of Messina, the narrow sea between Sicily and the Italian mainland. Preying on passing mariners, Scylla was a terrible creature with six heads and twelve feet, while Charybdis, living on the opposite side of the straits, was another monster who, over time, was transformed in the imagination of the ancients into a more rational, but no less lethal, whirlpool. Odysseus famously had to negotiate a passage through their deadly clutches in Homer's Odyssey.

Scylla

According to Hesiod, Scylla (or Skylla) was the daughter of Hecate who was associated with the Moon and the Underworld, and especially with ferocious hounds. Homer, however, names Scylla's mother as Crataiis. Her father is the sea god Phorcys but may also be Typhon, Triton, or Tyrrhenius, all figures with a sea connection. A later tradition makes her a beautiful mortal human who has affairs with Poseidon, Minos of Crete, and the sea god Glaucus until she is transformed either by the sorceress Circe or Poseidon's consort, the sea nymph Amphitrite, into a monster out of jealousy. The girl is caught unawares in her bathing pool, and when magic herbs are thrown into the waters, she turns into the hideous creature.

Scylla, whose name means 'she who rends' or 'puppy,' could only make the noise of a puppy dog, but she was well-endowed in other areas with six legs and six heads springing from various parts of her body, each with three vicious rows of teeth, so that her bite was definitely worse than her bark. Inhabiting a cave high up in the cliffs of the straits, Scylla would wait for unsuspecting prey – fish, dolphins, and men – to pass her way and then dart out one of her heads to drag the victim back into her lair to be crushed and eaten at leisure. Homer describes this fearful creature thus,

Nobody could look at her with delight, not even a god if he passed that way. She has twelve feet, all dangling in the air, and six long scrawny necks, each ending in a grisly head with triple row of fangs, set thick and close, and darkly menacing death. Up to her waist she is sunk in the depths of the cave, but her heads protrude from the fearful abyss, and thus she fishes from her own abode, groping greedily around the rock. (Odyssey, 12:87-95)

Homer, again through the warning voice of Circe, also describes the cliff where Scylla lives:

Its sharp peak...is capped by black clouds that never stream away nor leave clear weather round the top, even in summer or at harvest time. No man on earth could climb to the top of it or even get a foothold on it, not even if he had twenty hands and feet to help him, because the rock is as smooth as if it had been polished. But halfway up the crag there is a murky cavern, facing the West and running down to Erebus...Even a strong young bowman could not reach the gaping mouth of the cave with an arrow shot from a ship below...No crew can boast that they ever sailed their ship past Scylla unscathed...Scylla was not born for death: she is a thing of terror, intractable, ferocious and impossible to fight. (ibid, 12:75-120)

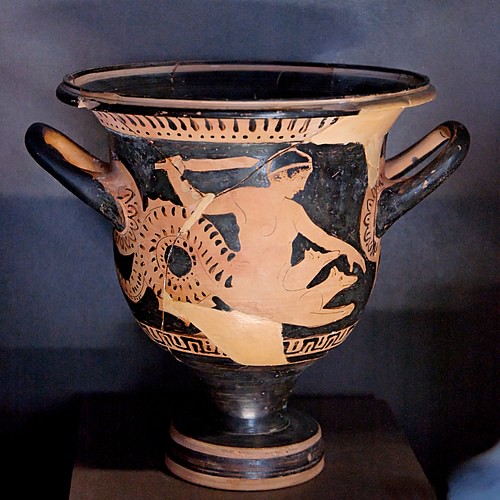

The 3rd-century BCE Greek tragedy poet Lycophron tells of a tradition that she was killed by the specialist in monster-slaying, Hercules, but, otherwise, Scylla's fate is unknown. Scylla appeared on the 5th-century BCE coins of both Cumae and Acragas (modern Agrigento on Sicily) and on numerous red-figure pottery vessels during the 5th and 4th century BCE, notably those of Attic and southern Italian red-figure pottery. She is typically portrayed as a type of mermaid with dogs heads coming from her waistline.

Charybdis

A monster of unknown description, Charybdis was thought to be the daughter of Poseidon and Gaia (Earth) and to dwell opposite Scylla in the same straits. She was thrown there after being struck by Zeus' thunderbolt, perhaps as punishment for her lustful character. Rationalised into a whirlpool or maelstrom, her waters were considered to suck in and blow out three times each day. Such was the powerful force of this turbulence that no ship could survive Charybdis' attentions.

Odysseus

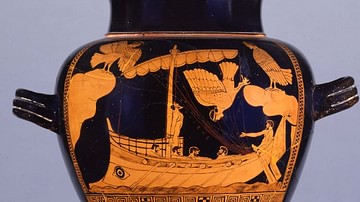

In Homer's Odyssey, the swirling waters of Charybdis famously wrecked the ship of the hero Odysseus on his way home from the Trojan War. Having just survived the sirens, the ship, in trying to avoid Charybdis, went a little too close to Scylla's lair. Six members of Odysseus' crew, the six best, were grabbed by the six heads of Scylla as they went through the turbulent waters of the narrow straits. The ship passed the still screaming victims and made it through the passage, but the escape was only temporary.

Landing on Sicily, Odysseus' men ignored strict instructions and cooked some sacred cattle which belonged to Hyperion. As punishment, Zeus then sent a storm and one of his thunderbolts which smashed the mast, killing the helmsman as it toppled. The ship was wrecked, the crew drowned, and only Odysseus survived by lashing together bits of flotsam. The gods were not quite finished, though, as another storm came and swept the hero right back into Charybdis. Odysseus was knocked about for a good while until he managed to escape by grabbing onto the overhanging limb of a wild fig tree. He then timed his exit by waiting for the waters to spew him out and away to safety along with the wreckage of his ship. After nine days adrift the hero's luck changed, and he landed on the island of Ogygia where the lovely Calypso aided his rest and recuperation for the next seven years.