Bangkok was once more commonly known as the Venice of the East due to the intricate network of waterways that crisscrossed the city in the 19th century CE. There were few roads in the 1800s CE so the city's inhabitants travelled and traded along the busy canals or khlongs on the Chao Phraya river - the major river of Thailand that flows through Bangkok.

It was a very green city filled with flowering flame trees boasting red and orange crowns, old tamarinds planted in the reign of King Chulalongkorn (1853-1910 CE), giant rain-trees with wide leafy canopies, and ficus trees wrapped in brightly-coloured ribbons that the Thai people believed would protect the spirits that dwelt within.

Bangkok in the 21st century CE, however, is a very different city. Many khlongs have been filled in with cement to make way for high-rise condominiums, hotels, and shopping centres, and those that remain are muddied by the devasting floods that regularly occur in a city built over a swamp. Old trees have been felled to create space for public art sculptures, extend congested roads or construct office towers. Pedestrians walking the city's humid streets are no longer provided with shade from overarching tree branches (a welcome exception being Wireless Road and Lumpini Park). Trees can cool cities by as much as 5°C (9°F) and lower humidity. True to say the first-time visitor to Bangkok often wilts on 35°C (95°F) days with 90 per cent humidity.

But there is a cool tropical oasis right in the heart of the city that has preserved a little part of the old Bangkok. Located within walking distance from the popular shopping centre Ma Boon Khrong (or MBK) and backing onto the still-used Saen Saeb Khlong is the Jim Thompson House Museum - one of the must-visit museums in Southeast Asia. Here you can step out of the Bangkok heat and stroll around half an acre of lush gardens dotted with shady banana, palm, and Indian cork trees, admire floating lotus flowers in large garden pots, and see calming pools of white Japanese Koi fish. A guided tour through this magnificent teak structure will introduce the visitor to two things - traditional Thai architecture and the history of Thai silk.

Jim Thompson (1906-1967 CE) was an adventure-loving American who lived in Bangkok following the end of World War II and disappeared in Malaysia in 1967 CE. He is called the Silk King because he helped save Thailand's centuries-old silk industry and created an international demand for this luxurious fabric. Before learning more about the mysterious and colourful Jim Thompson, let us take a look at the long history of textile production in ancient Siam (as Thailand was known until 1939 CE).

The Art Of Silk Making

The art of silk making is said to have its origins in China during the Longshan Period (c. 3000 BCE - c. 2000 BCE). Chinese legend tells us that a chance occurrence led to the discovery of silk. C. 2696 BCE, Empress Si Ling-Chi (also known as Xilingshi, Lei-Tsu or Leizu) was sitting under a mulberry tree in her garden enjoying a cup of tea when a cocoon dropped into her cup. The cocoon unravelled and the shimmering silk strands she discovered would result in the establishment of sericulture (silk farming). Sericulture remained a secret Chinese treasured for nearly 4,000 years and was fiercely guarded by making it a crime punishable by death for taking silkworms or their cocoons out of the country.

By the first millennium BCE, camel caravans laden with silk, silver, gold, and other precious commodities were travelling the Silk Routes (or Silk Road) from China through central Asia and onward to Egypt, Greece, Rome, the African continent and even Britain.

Up to the 13th century CE, only two known examples point to the existence of a Thai silk and weaving industry. The first example is the ruins of Ban Chiang, a Bronze Age (c. 3300 BCE- c. 1200 BCE) site in Udon Thani province, northeastern Thailand. Here archaeologists found the oldest recorded samples of silk fibres dating to between 1000-300 BCE along with spindle whorls and textile fragments. There is strong evidence to show that the Thais have a long history of weaving and working with textiles like hemp, cotton, and banana fibre.

Excavation sites have revealed that the ancient Thais knew how to weave and make rope from animal or plant fibres. Cord-marked pottery dating to around the 6th millennium BCE has been found in Mae Hong Son province in the north, including pottery with silkworm and mulberry leaf motifs.

There is little surviving historical or archaeological evidence to establish when silk production arrived in Siam. Most likely silk was introduced by the Chinese using a maritime route from a port on the west coast of Thailand on the shore of the Andaman Sea. There was, in fact, a Thai Silk Road through the south of Thailand that was used by foreign traders to transport goods by sea from the Greek and Roman empires to China and back. There were two ports or trading stations that were part of the world's ancient maritime trading routes - Phu Khao Thong in Ranong and Khuan Lukpat in Krabi province.

The second example is from the Sukhothai Period (1238-1438 CE). Sukhothai was the first Thai kingdom and was located in northeastern Thailand. Zhou Daguang (1266-1346 CE) was a young Chinese envoy who was on a diplomatic mission from the Yuan court to Cambodia. He recorded his visit in his memoirs, The Customs of Cambodia (1296-1297 CE) and noted that the Siamese people knew the art of weaving and sericulture.

Aside from these two examples very little is known of the Thai silk industry until 1861 CE when King Chulalongkorn, who was known as King Rama V (r. 1873-1910 CE), encouraged improvement in sericulture and started a silk production facility near Bangkok. But by the 1950s CE, sericulture had declined to the point that knowledge about the rearing of silkworms and the art of silk making was in danger of being lost. Even though silk weaving techniques and working with different textiles was a firmly established folkcraft in northeastern Thailand (particularly in Isan), the Thai royal court and elite imported highly-prized Chinese silk and Indian cotton.

Inferior quality cocoons and a lack of proper technical knowledge among Thai silk farmers were two reasons why the quality of Chinese silk was considered to be better. The Kingdom of Sukhothai also relied on imported silks from China and the Khmer Empire in Cambodia (802-1431 CE) despite strong evidence of local sericulture practices. Thai royalty by the end of the 19th century CE had also adopted Western-style dress.

The Buddhist faith of the Thai people prohibits any form of killing and the process of harvesting silk from the cocoon involves killing the silkworm larva. This also contributed to the decline of the Thai silk industry.

While national attempts to improve silk production faltered, the communities of Isan (which includes Ban Chiang) on the Khorat Plateau in northeastern Thailand, can probably be thanked for preserving the oral tradition of raising silkworms and producing provincial silk fabric with unique patterns and colours. Isan is bordered by the Mekong River (along the border with Laos) to the north and east and by Cambodia to the southeast. Hemp and cotton fabrics have been discovered at Isan's many prehistoric sites along with large blue glass beads, which were worn by men as an indicator of status. The earliest fabric in this region was most likely hemp dating back to 200 BCE, but traces of silk have also been found and dated to 500 BCE from Isan's Ban Na Dee site.

The Isan communities raised silkworms on a diet of white mulberry leaves and used natural dyes such as indigo, jack-fruit wood, cumin root, shellac from insects, mosses, berries, and turmeric tree bark, which gives cloth the distinctive yellow that is seen everywhere in Thailand.

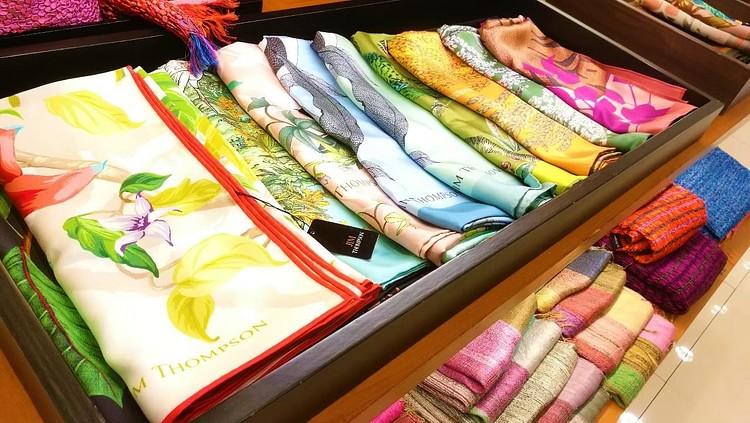

You can see many traditional silk designs at the gift shop attached to the Jim Thompson House Museum and you will also find out just how this intriguing American almost single-handedly rescued Thai silk, modernised the industry and turned it into a world-famous and sought after fabric. But his story and that of a revived Thai silk industry are not without its dramas.

Jim Thompson: Thai Silk Merchant

How Jim Thompson became involved with Thai silk is the stuff of Hollywood movies. It involves the clandestine world of international espionage, high society soirées, and mingling with royalty. The son of a textile manufacturer, James H. W. Thompson was born in 1906 CE in Greenville, Delaware. He became an intelligence officer in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which was the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). He spoke fluent French and served in North Africa, Italy, and France before being sent to Bangkok in 1945 CE just as World War II was ending. He was enchanted by a culture little known to the West and decided to remain in the exotic city at a time when few foreigners (or farangs in Thai) were living there.

Thompson had a keen sense of colour and immediately saw a business opportunity - the Thai silk industry which had almost been buried under the weight of cheaper and more durable machine-made silk despite government attempts in 1932 and 1941 CE to breath life into the industry. During the 1930s CE, he had worked in costume design for the renowned Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo so he had a sharp eye for textiles.

He came across a group of Cham Muslim weavers living in a small Bangkok community called Ban Krua, which is just across the Saen Saeb Khlong from the Jim Thompson House Museum. As Thompson later told Time magazine in 1958 CE: "It disturbed me that production of this wonderful material had stopped."

He resigned from the military in 1946 CE (although rumours have long circulated that he remained a freelance intelligence operative) and set off for New York with 500 samples of jewel-toned woven silk that dazzled fashion editors and designers. Thompson returned to Bangkok with a modest budget of USD 700.00, recruited 200 local weavers, provided them with raw silk from northeastern Thailand and introduced aniline dyes from Switzerland to replace the vegetable dyes used by the weavers.

He had a passion for Thai art and antiques and turned his attention to designing his own home to house his growing collection. He built a traditional antique wooden Thai-style house using temple doors from junk shop finds and gathered six old teakwood buildings from the ruins of Ayutthaya (c. 1351-1757 CE) - the second Siamese capital after Sukhothai. Thompson arranged the buildings into a complex separated by lush garden walkways and elevated them on stilts to protect from monsoonal flooding. The Thai people were no longer building in this traditional manner but they soon followed Thompson's example. This complex is now the Jim Thompson House Museum.

Locals referred to the complex as the House on the Khlong and visitors will see Thompson's artistic and architectural flair when taking a guided tour - black and white Italian-marble tiles on the first-floor landing, walls that face outward and painted red with a preservative in the style of old Thai houses, high-step room separators designed to protect from insects; an internal central staircase rather than the external staircase of Thai tradition. The tropical gardens are dotted with old statues and a spirit house to appease any spirits that may have been disturbed by the building of Thompson's house on old ground.

Perhaps the most unsettling aspect of a tour of Thompson's former home is the two framed horoscopes on the wall above his writing desk. One horoscope predicted good luck for 1959 CE and Thompson delayed moving into the house until that year. The other horoscope predicted bad luck when he reached the age of 61 years - Thompson was this age when he walked into a Malaysian jungle in 1967 CE never to be seen or heard from again.

You will hear many stories about his puzzling disappearance that perhaps overshadow his enduring legacy as the American who saved the dying art of Thai silk if you visit this magnificent museum.

How To Get There

The Jim Thompson House Museum is located on Soi Kasemsan 2, opposite the National Stadium on Rama I Road in the very heart of Bangkok. If you take the BTS Skytrain, stop at the National Stadium station and take Exit 1. Opening hours are 9:00 am – 6:00 pm every day and the entrance fee is 100 baht (around USD 3.20) and is free for children under ten years old.

If you do not like hot, muggy weather, it would be best to visit in December, January or February. And as you wander through the beautiful gardens, no doubt you will ponder Jim Thompson's mysterious disappearance. I have my theory. What is yours?