Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

(Karl Marx, Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right).

When it comes to religion, many people who seek it out, even the most powerful ones, do so to cope with difficult times or events. The innate fragility of the human mind forces the human being to create the desire to find out who is behind anything, good or bad. The fear of the unknown future, the desire to achieve a complete state of health, security, and happiness, and the continuous attempt to counteract inevitable events, combine altogether to bring into existence the play of worshipping the superhuman controlling power.

I don't know how many people reading this article have seen an epileptic patient with seizures? I always ask my students what is the meaning of seizure? All of them, undoubtedly, replied correctly. Actually, the objective of the question was draw attention to the root of this word. In ancient times, sudden and generalized trembling movements were not considered a disease; that person was “seized” by an evil spirit for certain reason, people said. This concept has not changed since then, sad to say; many people still believe in this!

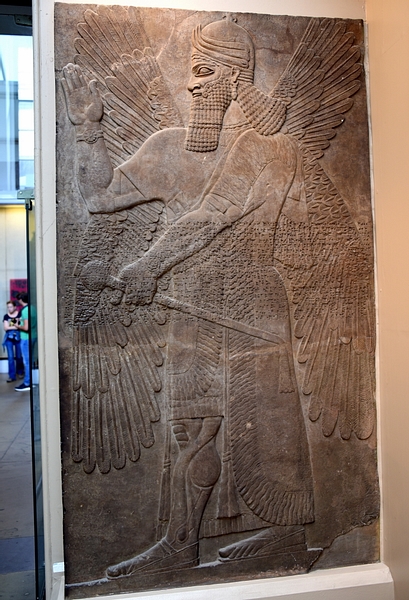

This human-headed and winged Apkallu (left, together with the Lamassu on the right) guards and protects Room 6 on the ground floor of the British Museum. Alabaster bas-relief. Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Panel 2, originally from Room Z in the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The sages' story

The Mesopotamian literature about the concept of creation was very elaborate and this gave birth to the broad subject of Mesopotamian religion. Gods and goddesses communicated with humans via an intermediary. Accordingly, after the Earth and mankind were born, seven wise men or sages were created by the god Enki to establish culture and give civilization to mankind. Apart from being emissaries, those sages taught humans the moral code, arts, crafts, agriculture, copulation, etc. Some sages are said to have acted as advisors to some Sumerian kings before the Flood. The myths say their appearance was fish-like. Their precise names, general appearance, and “order” of creation by Enki is still a matter of debate, and of course, outside of the scope of this article.

After the Flood, the sages' appearance changed. Humans and sages were capable of conjugal relationships; therefore, a new generation of sages (scholars suggested four in number) was created. Partially human and partially superhuman creature, the sage's role was mainly to be an adviser to Sumerian kings. The Epic of Gilgamesh tells that sages participated in the construction of the great walls of the city of Uruk in Southern Mesopotamia; however, Gilgamesh's advisors were only human beings. This diversion from the usual norm at that time was striking.

These sages are depicted on a number of reliefs and are known as Apkallus (Apkallu is "sage" in Akkadian; they are known as Abgal in Sumerian). Three types of Apkallus (human-headed, eagle or bird-headed, and fish-like) were placed at doorways or room/hall corners of the North-West Palace. The installation was not haphazard; people thought that evil spirits lurked in doorways or corners. Sometimes, a group of Apkallu statuettes were buried beneath the floor. To augment this protection, colossal Lamassus (protective deities with human heads but winged lion/bull bodies) were also guarding doorways. Neo-Assyrian sculptors working between 911-612 BCE have left us an invaluable and priceless legacy of stone, documenting the shape and duty of Apkallus. Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 884-869 BCE), a harsh, merciless, and inexorable King, decorated the walls of his North-West Palace at the Assyrian capital of Nimrud with state-of-the-art, two-meter high alabaster bas-reliefs depicting a multitude of ritual, court, and vivid war scenes. Here, the innate habit struck and made an impact; even this stony-hearted and cold-blooded King looked for supernatural creatures to protect him and his palace against evil!

Room 7 (Assyria, Nimrud) and to lesser extent Room 6, of the British Museum, houses the largest collection of these wall panels of any museum, in an excellent state of preservation. I remember, the very first time I visited the British Museum, I rushed into Room 7, skipping everything else, to live the moment and enjoy the scent of my history!

Basic characteristics

Undoubtedly, visitors of the British Museum will be overwhelmed by the number and content of these wall panels. When you are in hurry and skimming them, you will think that the Apkallus are similar. In fact, no. There are many similarities and dissimilarities, but superficially, they look alike!

Supernatural creatures, winged genies, and protective spirits are the terms used to describe Apkallus. Even if they are of the same type (human or bird), they were sculpted differently. Their helmet or headdress, beard, hair, moustache, earring, necklace, dress, and other accessories are all different from each other, even their facial expression! Some are bare-footed and some wear sandals. “The Standard Inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II runs horizontally across all of the reliefs. When you see the images below, you will find out that the sculptors were very professional at placing and distributing the carved cuneiform signs of the Standard Inscription text; this is one of my favourite skills of art!

Apkallus are winged. They can have a pair of wings or two pairs of wings (i.e., two or four wings). Because they are depicted in profile, sometimes only three out of four wings appear; eagle-headed Apkallus usually demonstrate three wings on the reliefs. They either accompany Ashurnasirpal II (as well as his courtiers, attendants, and guards) in a ritual or court scene, or flank or face the so-called Sacred Tree or Tree of Life (a palm tree with palmette motifs) in the absence of the King. They usually stand; sometimes, they kneel at the Sacred Tree. The so-called South Suite of the Palace, which is believed to have been the King's private living area, is mostly devoid of any Apkallu (or even the King's images).

There are two outstanding wall reliefs depicting a different overall appearance. One is a human-headed Apkallus holding a goat with one hand and what appears to be (according to the British Museum) a large ear of corn in the other hand. The other Apkallu holds a deer and a palm branch. Here, I have a whole article dedicated to these Apkallus.

All of these slabs were unearthed by Sir Henry Layard during his work on the city of Nimrud during mid-19th century CE; they reached the British Museum after few years. Now enjoy the images!

The Apkallus' heads

The British Museum houses human-headed Apkallus (most are males, but there are females also), bird-headed (of an eagle), and what appears to human-shaped but fish-like or wearing a fish cloak. The latter's image can be seen above. In general, their body parts' anatomy and musculature were exaggerated; a bodybuilder's physique. All were depicted in profile.

Head of a winged protective spirit. This is an image of a “human adult male”. Note the terrorizing look. He wears a three-horned helmet or head cap and an earring. Note the fine and exquisitely carved details and compare them with the two images below. For example, the helmets, eyebrows, eyes, shape of the nose, the diameter of the curls of the beard, the wavy hair, and his facial expression.

Head of a human-headed and winged protective spirit. He wears a two-horned (not three-horned) helmet. This spirit protects Ashurnasirpal II in a court ritual scene in Room G; this room was part of the so-called “East Suite”, where the King performed prayers and ceremonial rituals. Only high-ranking advisors and temple priests had access to this room. Compare this image's details with the above image. This spirit's facial expression is less hostile.

Head of a human-headed and winged protective spirit. He does not wear a helmet; instead, he wears a diadem or a fillet with a rosette at the centre. The details of the diadem were very finely and beautifully carved. Each spirit wears a different type of earring; compare! Overall, his head seems to be rounded and “thick”; compare this with the image above, where the spirit's head appears a little bit elongated. This spirit was protecting the door of Room T; this was a small room, which was connected to Room S. Room S was the King's private area and part of the “South Suite” (most of the rooms in this private area did not contain Apkallus reliefs).

Head of a human-headed and winged “female” protective spirit. She wears a two-horned helmet and an earring. Compare the shape of this helmet with the helmet of her male counterpart. This panel's spirit protects Room I. Room I was part of the L-shaped inner rooms of the East Suite; Room I was even more highly secured from divine and human intruders.

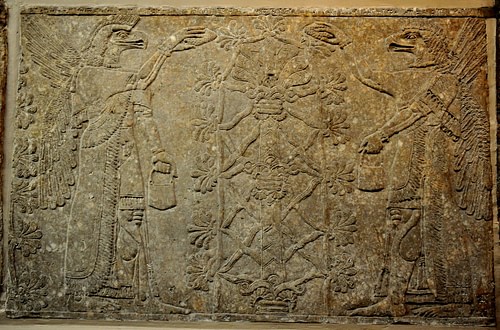

Eagle-headed apkallus

Eagle-headed Apkallus are usually depicted beside the Sacred Tree; this might represent an additional fertilization function. A whole room, Room F of the Palace, was heavily lined and decorated with this kind of image.

This is an eagle-headed protective spirit; a male, not a female. He does not wear a headdress; the feathers, which appear on his head, are part of his wing, behind the head and neck. Scrutinize each and every detail of this head; the peak, tongue, strange-looking eyebrow, small ear with feathers, feathers on the front of the neck, and the double-layered curls on the scalp hair. He does not wear an earring but wears a necklace with a pomegranate or a blossom at the front. Compare this eagle's image with the eagle below.

Another head of an eagle-headed and winged protective spirit. This spirit was in Room F. This room is adjacent to Room B (the Throne Room) and was entirely panelled by eagle-headed protective spirts and the so-called Sacred Tree or Tree of Life. This room was probably used by Ashurnasirpal II to rest after (or before) meeting with people in the adjacent throne room.

Hand-held items

What do their hands hold? This is different depending on the scene an Apkallu appears in. Options are a small bucket in the left and a pine cone in the right - the most common depiction; a chaplet in the left hand while the right hand is empty and raised; the left hand holding a flowering branch while the right is empty and raised; or, occasionally, the left hand may be holding a mace while the right hand is empty and raised. None of the Apkallus has two empty hands, and they don't hold swords or bows and arrows; instead, several types of daggers were tucked into their waistbands.

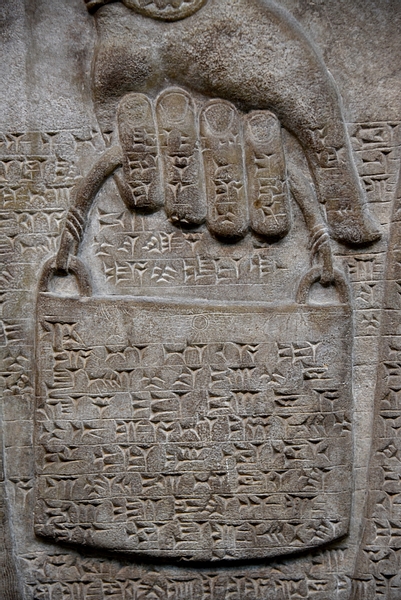

The banduddu or bucket

The left hand may hold a small bucket (banduddu in Akkadian) filled with fluid. Dr. Mouad Saed Al-Damirchi, former director general of the General Directorate of Antiquities in Iraq, once told me that this fluid might be water of melting snow; Assyrians thought that the snow on the mountains is scared as it comes from the sky (gods/goddesses). This, combined with a pine cone in the right hand, is the commonest depiction. Each Apkallu holds a different bucket from the others.

This bucket, filled with fluid, is held by the left hand of a human-headed protective spirit. The pail's ends are fixed into bird-shaped mounts. Note how the sculptor scratched the horizontal lines in order to carve “the Standard Inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II. The spirit's hand and bucket are covered with few cuneiform signs. Scrutinize well and compare these fine details with the those of the four examples below; all of these buckets are different from each other.

Just below the mid-part of the upper rim of this bucket, there is a winged disk, a symbol of the god Assur. The sculptor carved the cuneiform signs all over the fingers of the protective spirit's left hand and the bucket.

![Bucket Held by an Apkallu [2]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/500x600/7296.jpg?v=1599481805)

This is the left hand of a human-headed protective spirit, who stands behind Ashurnasirpal II (not shown here) holding a bucket.

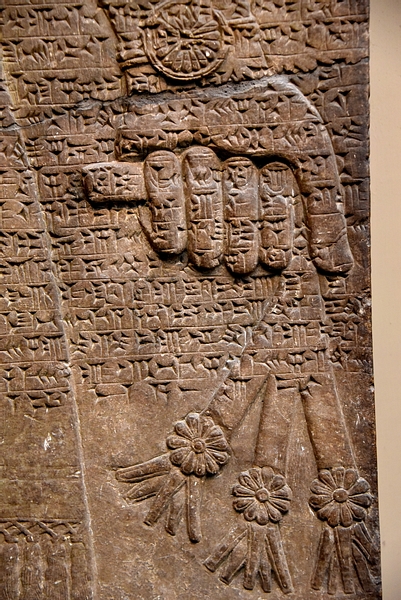

The left hand of an eagle-headed protective spirit holds a bucket. Note the absence of cuneiform signs in this panel, because the “Standard Inscription” was carved above the panel.

An eagle-headed protective spirit holds a bucket, devoid of cuneiform signs. Note that the bottom of the bucket is not flat.

The pine cone

When the left hand holds a bucket, the right hand usually holds what appears to be a pine cone (mullilu in Akkadian). The Apkallu dips the cone into the bucket and sprinkles the King (and the people around him) with that fluid in ritual ceremonies to purify them.

The right hand of an eagle-headed protective spirit holds a pine cone and sprinkles fluid on the back of the head of the King (left lower part of the image represents the King's hair).

The right hand of a human-headed protective spirit holds a pine cone and sprinkles fluid on the back of the head of a royal attendant; the tip of the cone lies in front of the string of the bow held by that attendant.

The chaplets

It also occurs that the left hand holds a chaplet while the right hand is empty but raised (the fingers are extended and held together) so that the right palm faces the viewer. This can be seen with female human-headed Apkallus flanking the Sacred Tree, not the King. This gesture suggests that the Apkallu is performing an act of worship or prayer.

The left hand of a human-headed female protective spirit holds what appears to be a string with beads or chaplet; she seems to perform an act of worship or counting prayers. Cuneiform signs were carved on the surface of the hand and fingers but only on one bead of the chaplet. The right hand (not shown) is raised and holds nothing.

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Detail of Panel 16, Room I, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

The left hand of a human-headed female protective spirt holds a chaplet. There are no cuneiform signs.

The flowering branches

Another possible depiction is the left hand holding a flowering branch while the right hand is empty and raised. Once again, these branches are used in religious ceremonies and during the act of worship. Needless to say, the shape of the flowering branch is different.

The left hand of a human-headed protective spirit holds a flowering branch with blossoms while performing an act of worship. There are no cuneiform signs.

The left hand of a human-headed protective spirit holds a flowering branch. Note the placement and distribution of the cuneiform signs.

The left hand of a human-headed protective spirit holds a flowering branch. Note the absence of inscriptions.

The left hand of a human-headed protective spirit holds a flowering branch. There are no cuneiform signs.

The mace

Lastly, the left hand can also sometimes be seen holding a mace (a symbol of authority) while the right hand is empty and raised. This scene is visible in the depiction of an Apkallu guarding a doorway into the Throne Room.

The left hand of a human-headed spirit holds a mace; the right hand is raised and does not hold anything.

The Apkallu's empty hands

The right hand of a human-headed protective spirit; the palm faces the viewer and there are typical human palm creases. He wears two bracelets.

The raised right hand of a human-headed protective spirit. Note the absence of palm creases and the bracelet with a rosette.

The Apkallus' daggers

Two daggers within their sheaths are carried by an eagle-headed protective spirit. They are tucked into his waistband. Note the overlying carved decorative motifs.

Two daggers were tucked into the waistband of a human-headed female protective spirit. There are no overlying decorative motifs.

One of the handles of these three daggers is shaped like what looks like it could be a ram's head. The daggers were inserted into the waistband of a human-headed protective spirit.

Another human-headed protective spirit carries three daggers; one of the handles of these three daggers appears to be in the shape of a ram's head. The daggers are tucked into the waistband.

Complete panels

Neo-Assyrian Period, 865-860 BCE. Panel 16, Room I, the North-West Palace at Nimrud, modern-day Iraq.

This panel depicts a pair of human-headed and winged female protective spirits flanking the so-called “Sacred Tree or Tree of Life”, and performing an act of worship. Note what they wear, hold, and do. Two wings appear only, for each one; compare this with the two images below.

This complete panel shows a pair of eagle-headed and winged protective spirits flanking the so-called “Sacred Tree or Tree of Life”, and performing an act of worship. The Assyrian sculptor depicts eagle-headed spirits having three wings while the human-headed spirits display two or four wings.

This human-headed protective spirit has four wings. He guarded one of the entrances to the King's Throne Room.

When you visit the British Museum, spend some time focusing on these wonderful details. I hope in writing this article, I have drawn our readership's attention to this Assyrian art and mythology's details. I couldn't and I cannot include all zoomed-in images of all panels I have; instead, I have chosen a few examples to demonstrate.

This article was written in memory of Sir Henry Layard (1817-1894).

Archaeology holds all the keys to understanding who we are and where we come from.

(Sarah Parcak).